Karel Janeček − a leading figure in Czech Music Theory and Pedagogy: his theoretical writings from the 1930s and 1940s

Miloš Hons

Karel Janeček (1903–1974) was a groundbreaking figure in Czech modern music theory. Although he was active as a scholar and a composer, his place in Czech music history rests on his theoretical work. He was the originator of a new model for university-level music theory teaching, setting up a framework whose essence is still in use today. After a brief period of teaching at the Prague Conservatory, he spent the following three decades of his career at the Academy of Performing Arts in Prague (AMU), where he was head of the Department of Music Theory. His work as a teacher of players, singers, conductors, music directors and, most notably, composers served Janeček as an empirical testing ground for the premises, concepts, and systemic principles he came to formulate in his major books and essays. Viewed from a historical perspective, his most significant books include Základy moderní harmonie (Modern Harmony, 1949, published 1965), Hudební formy (Musical Forms, 1955), and Tektonika – nauka o stavbě skladeb (Tectonics: A Theory of the Structure of Compositions, 1968). Janeček´s teaching commitments at AMU were centered around two theoretical courses whose concepts he drew up and put into practice: namely, Nauka o skladbě (Theory of Composition), which was later renamed Study of Compositions. With the passage of time, as Janeček brought out his essential theoretical writings, his theory of composition came to serve as an obligatory supplement to all disciplines of music theory. It was focused on three areas: (a) modern harmony, (b) melody, and (c) tectonics.

The study deals with two little-known areas of Janeček’s theoretical activity. First of all, there are early studies from the 1930s, a period in which he was teaching at the Music School in Plzeň. At this time, Janeček began to focus on the issue of modern harmony, and most of these articles are preparatory work for his first monograph, Modern Harmony, completed in 1949. Janeček created an original systematics of harmonic material using as few as two and as many as twelve notes in an equal-tempered system. Its classification and determination of dissonant or consonant characteristics apply to both the chords of traditional Classical-Romantic music and to modern music of the twentieth century. At this time, he also devoted himself to the analysis of Bedřich Smetana’s music. In these analyses we find the beginnings of his completely original concept of musical tectonics. Janeček thus created a new subdiscipline and analytical method (tectonic analysis).

The second topic of the study is a critical analysis of Janeček’s completely unknown textbook Kontrapunkt (Counterpoint), which was created in the 1940s and was intended mainly for conservatory students. Unfortunately, the text remained unfinished, but testifies to his original approach to teaching counterpoint. Janeček’s main concern was to explain the essence of individual contrapuntal techniques, focusing on their practical application. Therefore, he limited the historical aspect and applied his specific analytical and compositional method to explain the basics of vocal counterpoint.

Karel Janeček (1903–1974) war eine führende Persönlichkeit im Begründungsprozess einer modernen tschechischen Musiktheorie. Neben seinem Wirken als Gelehrter und als Komponist ging er in die Geschichte der tschechischen Musiktheorie als Urheber eines neuen Konzepts von Musiktheorie mit dem Anspruch einer universitären Disziplin ein, indem er Rahmenbedingungen einführte, die im Kern bis heute als Modell weiterwirken. Nach einer kurzen Phase, während der er am Prager Konservatorium lehrte, verbrachte Janeček die folgenden drei Jahrzehnte seiner Karriere an der Akademie für Darstellende Künste (AMU) in Prag, wo er die Musiktheorieabteilung leitete. Seine Arbeit als Lehrer von Musiker*innen, Dirigent*innen, Musikdirektor*innen und insbesondere Komponist*innen diente ihm als Experimentierfeld für die Grundsätze, Konzepte und systematischen Prinzipien, die er in seinen wichtigsten Büchern und Essays formulierte. Von weitreichender Bedeutung sind seine drei Hauptschriften Základy moderní harmonie [Moderne Harmonie] (1965), Hudební formy [Musikalische Formen] (1955) und Tektonika – nauka o stavbě skladeb [Tektonik – Eine Theorie über die Struktur musikalischer Kompositionen] (1968). Im Zentrum von Janečeks Unterrichtstätigkeit an der AMU standen zwei musiktheoretische Kurse, deren Konzepte er bündelte und in die Praxis umsetzte, darunter die Kompositionstheorie, die später in Studium von Kompositionenumbenannt wurde. Mit der Veröffentlichung seiner theoretischen Schriften diente Janečeks Kompositionstheorie zunehmend als obligatorische Ergänzung zu allen weiteren musiktheoretischen Disziplinen. Sie zielte auf drei Bereich ab: a) moderne Harmonie, b) Melodie sowie c) Tektonik.

Die vorliegende Studie beschäftigt sich mit zwei wenig bekannten Aspekten von Janečeks theoretischem Wirken. Zunächst geht es um frühe Studien aus den 1930er Jahren, in denen Janeček an der Pilsener Musikschule lehrte. Frühzeitig spezialisierte er sich auf dem Gebiet der modernen Harmonik, und die meisten Arbeiten aus dieser Zeit sind Vorbereitungen der ersten Monographie Moderne Harmonik von 1949. Janeček entwickelte eine spezifische Systematik des harmonischen Materials von Zweiklängen (Intervallen) bis hin zu Zwölftonharmonien im Rahmen der gleichschwebend temperierten Stimmung. Seine Klassifizierung und Bezeichnung dissonanter sowie konsonanter Klangeigenschaften gilt sowohl für die Akkorde der traditionellen klassisch-romantischen Musik als auch für die der Moderne des 20. Jahrhunderts. In dieser Phase widmete er sich überdies der Analyse von Bedřich Smetanas Musik. Seine Analysen zeigen Ansätze eines völlig neuen Konzepts von tektonischer Analyse.

Der zweite Gegenstand der Studie ist eine kritische Analyse von Janečeks unbekanntem Textbuch Kontrapunkt, das in den 1940er Jahren entstand und hauptsächlich für Studierende an Konservatorien bestimmt war. Diese leider unvollendet gebliebene Schrift dokumentiert den ursprünglichen Ansatz von Janečeks Kontrapunkt-Unterricht. Sein Hauptanliegen war, essentielle sowie individuelle kontrapunktische Techniken zu erklären und zu zeigen, ›wie es gemacht wird‹. Daher gab er historischen Gesichtspunkten nur begrenzt Raum und wandte seine eigene analytische und kompositorische Methode an, um die Grundlagen des Kontrapunkts zu erklären.

Introduction

Karel Janeček (1903−1974) was, in the true sense of the word, the founder of modern Czech music theory. His most important writings not only influenced all Czech scholarship on music in his own time, but also the theorists of future generations. Despite this state of affairs, there are hardly any critical assessments of Janeček’s work: there are only a few brief reviews of his books, written by Janeček’s collaborators and teachers.[1] In the 1980s, Marta Ottlová published a list of Karel Janeček’s compositional and theoretical works, and in the 1990s Jaroslav Smolka published a brief monograph with a basic overview of Janeček’s work.[2] The most valuable, but also the oldest, critical reflection on Janeček’s theoretical writings is Karel Risinger’s book entitled Vůdčí osobnosti české moderní teorie (Leading Personalities of Czech Modern Theory), which was written in the late 1950s.[3] For these reasons, this book does not contain a critique of Janeček’s major works, which were published only later.

The author of this study has explored Janeček’s theoretical work for many years and his published studies are the result of a systematic research of Janeček’s estate. Unfortunately, none of Janeček’s writings have yet been translated into English or German, so his work and opinions are unknown abroad. The study has two main objectives:

1. a critical reflection on Janeček’s early writings from the 1930s and 1940s, dealing with issues of harmony and musical analysis. These studies form a kind of preparatory work for his later large writings.

2. a critical analysis of an unknown and unfinished work on counterpoint, containing a number of original insights on the systematics of counterpoint and its teaching.

So that the reader can understand the context in which Janeček’s ideas developed, the study also contains a brief description of Janeček’s most important and original theoretical works on modern harmony and musical tectonics.

In the 1920s, Janeček studied composition at the Graduate School of the Prague Conservatory with Vítězslav Novák. Even as a student, he was characterized by a broad intellectual outlook, which was made possible by his knowledge of five European languages.[4] His studies at a technical school and certain personal character traits shaped his specific systematic thinking. His tendency toward theoretical research, which was present even when he was a student, found an outlet in his journalistic writings. In the period between the two world wars, the only two respected music theorists in Czechoslovakia were Alois Hába and Otakar Šín. However, their importance and contributions were thematically and temporally limited.

The theoretical works under discussion here relate to the time when Janeček began his career as a teacher of music theory at the Music School in Plzeň. His thoughts were based on the tradition of Classical-Romantic music, but we find a clear orientation toward modern music of the twentieth century, and thus toward modern harmony. Janeček’s theoretical development intensified in the 1940s, when he became a professor of composition at the Prague Conservatory. Janeček’s activity increased after the Second World War through important theoretical and pedagogical work, which he conceived as the head of the Department of Music Theory at the Faculty of Music of the Academy of Performing Arts in Prague (from 1946 to 1974).

Figure 1: Karel Janeček around 1970. Reproduction from the archive of Miloš Hons

Theoretical writings from the 1930s (harmony, music analysis)

Janeček was steered towards a professional career in teaching by his father-in-law, at whose instigation he chose, after completing his Graduete School studies, to apply for the job as a theory teacher at the Bedřich Smetana Municipal Music School in Plzeň. Beginning September 1929, he was given a teaching assignment of twenty-four hours per week, divided between several areas of music theory, with the largest share being taken up by the theory of harmony. His teaching assignment prompted Janeček to engage in pedagogical research.

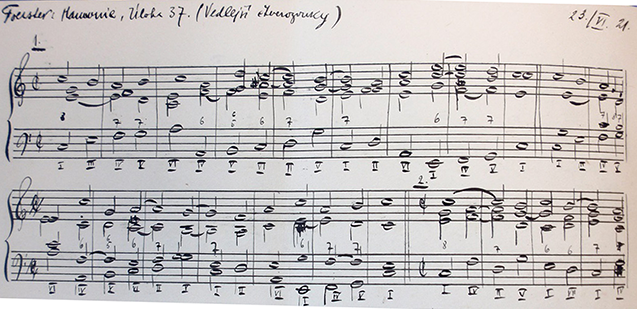

The focus of his attention was harmony, which he taught himself, even while at the Prague Conservatory mainly from textbooks by Josef Förster, Zdeněk Skuherský, and by the composer Leoš Janáček. He studied Förster’s textbook in its entirety and developed many exercises in general bass. As a composer and pedagogue, Janeček realized that the teaching of harmony needed to be modernized both in terms of content and methodology. He generally criticized old textbooks for the lack of illustrative material from music literature and thus the omission of analytical practice. This view became the central theme of most of his studies from the 1930s; the following quotation from 1944 is representative:

Förster’s Theory of Harmony, although excellently compiled from a pedagogical point of view, was limited almost exclusively to elaborating a general bass, while the harmonization of the melody was addressed only in a few paltry pages somewhere at the end; in its own theoretical material it provided regulations without a deeper interpretation of the essence of music. As a whole, it became so old that only in the most primitive questions could it provide support to an advanced composition student. Skuhersky’s forgotten handbook was a bold experiment that could not be used as a textbook. The same goes for Leoš Janáček’s Harmony.[5]

Figure 2: Janeček’s examples from the textbook of harmony by J. Förster (1921). Reproduction from the archive of Miloš Hons

Before characterizing the early studies of harmony, we can present the basic postulates, toward which Janeček gradually worked, and which form the basic pillars of his later systematics of modern harmony:

1. The starting harmonic material is a twelve-tone tempered series in which all altered tones have an equal position.

2. The default harmonic unit is the interval, i.e., the relationship between two sounds.

3. Chords may be composed of intervals other than thirds.

4. Inversions of chords represent separate harmonic units.

5. The classification of chords is based on the number of dissonances that they contain.

6. The semitone, whole tone, and tritone are dissonant intervals; the augmented triad is a special type of dissonant chord.

7. The only consonances are major and minor triads.

In the early 1930s, Janeček wrote several methodological articles for the education department of the magazine Tempo, whose editor was Adolf Cmíral. The article “Směrnice pro účelné rozvržení látky v harmonii” (Instructions for a Rational Structuring of Subject Matter in the Teaching of Harmony),[6] from September 1931, remained unpublished. Its content makes it obvious that he had already come to believe that the teaching of music theory ought to be divided into two qualitative categories: namely, those of teaching for composers, and teaching for performers. The basic criterion of acquiring a theoretical knowledge of harmony was its applicability, i.e., students ought to accumulate theoretical information about something they had already known from practice. This premise became central to Janeček´s approach and recurs in his writings throughout the rest of his life. He first conceived his version of the methodology of harmony in accord with the possibilities then offered by his posting at the Městské hudební škole v Plzni: he taught two lessons per week fortwo academic years. The course was divided into stages, starting with acquaintance with chordal forms and their dissonant character, to harmonization of soprano melody, to combinations of chords, modulations, and free harmonic connections without tonal bindings. There, he called for focus on the internal tension and motoric energy of harmonies.

Already these early studies reveal the influence of the opinions of the representatives of the so-called dynamism led by Hugo Riemann. Like Riemann, Janeček understood music as a process, that can only be grasped retrospectively, as it takes place in time and is organized in a form. He considered the eight-bar period to be the foundation of compositional structure. The dynamic conception of melody, harmony, form, and structure appears through Janeček’s entire theoretical work. This is evidenced by the fact that, in Musical Forms (1955) and especially in Tectonics (1968), Janeček paid considerable attention to the issue of musical time and the temporal arrangement of a composition. In addition, in Tectonics, Janeček took a rather negative view of Riemann’s analyses of Beethoven’s piano sonatas and considered them to be a frightening example of one-sided focus on form. On the contrary, in Melody (1952), Janeček agreed with Riemann that every melody is periodic, but often with deviations, such as widening, narrowing, or metric reassessment. Riemann’s dynamic conception of form was reflected in Janeček’s functional interpretation of the form, arrangement, and structure of compositions (see main and secondary tectonic functions below).[7]

As for figured bass, he proposed its teaching should be reserved for students preparing for the state examination in music, where he was often present as a member of the board of examiners. For chord symbols, he preferred functional ones (T, S, D, TVI, DVII), to the use of mere scale degrees. To obtain basic information about the harmonic material used in modern music, he recommended an extensive body of harmonic analyses with examples of non-tertian chordal texture.

In 1931, he published another didactic article, “Rozvoj harmonické představivosti jako otázka pedagogická” (The Development of Harmonic Imagination as a Pedagogical Issue).[8] He regarded harmonic imagination as the most reliable capacity conducive to the understanding of all harmonic phenomena. To him, the concept combined three premises pivotal to the teaching of harmony. He called the first of these the formal premise, consisting of an objective and systematic explanation of harmonic principles and rules, including the knowledge of basic terminology. The prerequisites of an adequate understanding of this premise are the students’ mental maturity and corresponding age. To make the subject matter readily accessible, the teacher should choose a historical period in music whose harmonic material offers the potential of a maximum degree of understanding by a learner at a given stage. Janeček believed this was best exemplified by Classical and Romantic music from the period between c. 1780 and 1890, which makes possible deductions about the elementary principles for the first stage of teaching the theory of harmony. The second principle of harmonic imagination lies in the psychological basis, i.e. in the gradual development of a sense of harmonic relationships. The third premise of imagination was determined by the historical framework, or the criterion of historical perspective encompassing the development of harmony, which is a crucial prerequisite of understanding stylistic features. As regards the explanatory aspect of lecturing, he required the presentation of multiple examples from musical practice, a requirement he revised in subsequent years, for the sake of artificially created examples instrumental in explaining a phenomenon under discussion with sufficient clarity:

Theoretical principles ought to be demonstrated through examples selected specifically from music literature, since only immediate interconnection between theoretical study and practical observation can guarantee at least to some extent that gifted students will continue to follow the harmonic aspect of music even after completing their studies, thereby also cultivating their hitherto immature capacity of imagination.[9]

The development of Janeček’s trend towards the systematics of twentieth-century harmony is demonstrated by a study entitled “Moderní harmonie” (Modern Harmony).[10] He based his interpretation of the developmental laws of modern harmony on the classical tonal system. He identified two basic principles that had contributed to the increasing complexity of harmony in the twentieth century: (1) gradual expansion of chordal species from triads to include up to twelve tones and (2) deformation, i.e., the alteration of existing chordal structures. According to Janeček, the impetus for the development of modern harmonic means was hidden kinetic energy, or rather the tendency for its stabilization and release in various directions. Harmonic freedom was not a manifestation of creative anarchy, but a proof of the growing subjectivity of contemporary music. In the above-mentioned study, we also encounter for the first time Janeček’s important theorem − imaginary tones (imaginární tóny).

If we play a melody or a sequence of chords continuously (legato), one or more real tones sound in any vertical cross-section. If we play the same melody or sequence of the same chords by separating the individual tones or chords with pauses, then even during each pause, the tones that sounded just before - these are just imaginary tones.[11]

According to Janeček, imaginary tones are one of the most distinctive features of modern harmony. In harmonic connections, in addition to real tones, certain imaginary tones also survive in memory. These then contribute to the melodic-harmonic conclusion of the phrase. With perfect harmonic connections and conclusions, it is necessary to cancel these imaginary tones. It is canceled by the onset of a real tone at the distance of a semitone or a whole tone.

Janeček was aware that the existence of imaginary tones is a matter of inner ideas, a real phenomenon whose existence can be heard, but not seen in notation. He also provided a theoretical interpretation of this phenomenon in his article “O významu imaginárních tónů v harmonii” (On the Significance of Imaginary Tones in Harmony) from 1932.[12] When describing the harmonic field, Janeček leaned towards his own opinion that even a monophonic melody has its own harmonic content, hidden (latent) harmony, and that, conversely, harmony is a vertical abbreviation (sometimes a complete summary) of the melodies of a given material.

He returned to this issue in another study “Vznik, stavba a ráz nových souzvuků” (The Origin, Structure, and Character of New Harmonies),[13] in which he broadened his analytical view of non-traditional chord formations found in styles, being historically distant from each other − in the works of Perotin, Machaut, Monteverdi, Bach, Mozart, Beethoven, and Novák. He identified Jean-Philippe Rameau as the founder of the theory of modern harmony and paraphrased one of his key ideas in the study:

At first, harmony seems to have its origin in melody, in that the melody created by each voice becomes their union of harmonies; but each of these voices first had to be given a way so that they could resonate properly [...] So harmony leads us and not melody.[14]

According to Janeček, the harmonic cadences so usual in every classical harmonic sentence, gave rise to so-called basic harmony, and the harmonic formations arising from the movement and suspension of voices gave rise to so-called passing harmony: “Passing harmonies have become a model for the creation of new basic harmonies, this process continues to this day.”[15]

In the unfinished study Třídění harmonického materiálu[16] (Classification of Harmonic Material, 1932), he proposed a modernization of the pedagogy of harmony, both for composers and as a supplement for performers. He emphasized the need to acquaint students with contemporary harmonic material, including non-tertian chords. Further, he described a need toreimagine traditional views of dissonance and consonance, the kinetic energy of chords, alterations, and modulations. He solved the quarrel in the field of chord marking, i.e., step and combination (referring to relationships between chords), with his own concept based on the awareness of tonal functionality. He designed markings for individual stages – T, SII, TIII (or DIII), S, D, TVI, DVII.

In the study “Rozvrat diatoniky” (Disruption of the Diatonic System),[17] Janeček also commented on contemporary reactions to recent work, specifically Schönberg’s twelve-tone composition. He considered the expansion of the diatonic system to twelve-tone to be a positive phenomenon. However, this does not mean that the establishment of a twelve-tone system implies a complete denial of diatonic system and its melodic-harmonic possibilities.

In the following theses, Janeček also theoretically refuted some of the most common rumors and errors promoted by opponents of Schönberg and his music:

1. It is not true that twelve-tone music is expressively poor and monotonous. A certain monotony of the whole is required by the constructional functions of the parts, but a general lack of contrasts is a manifestation of poorness in every type of music. Unlike diatonic music, twelve-tone music provides broader and more efficient harmonic possibilities and not just a few constantly changing types.

2. It is not true that twelve-tone music is chromatically creeping and is thus incapable of energetic harmonic motion. A twelve-tone composition is not free-flowing, chromaticized diatonic music. Its harmonic content includes the meaningful combination and deformation of chordal shapes.

3. It is not true that twelve-tone music is an expression of spiritual anarchy and acts as a “sticky caustic at the healthy roots of diatonic music.”[18] For Janeček, a complete return to the diatonic music of the “past” was historically impossible.

Among his theoretical-analytical studies of the 1930s, the third “Forma a sloh Mé vlasti” (Form and the Style of Má vlast)[19] occupies a leading position. At the time, it was the most mature and theoretical work about Smetana, following Josefa Hutter’s analyses of Smetana’s Swedish symphonic poems[20] and Otakar Zich’s analyses of Smetana’s symphonic poems.[21]

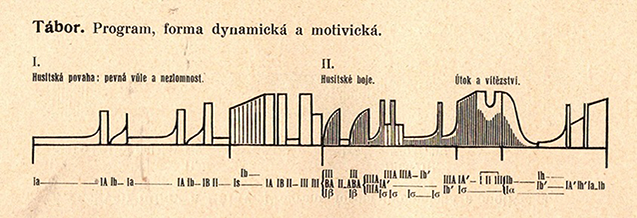

Zich’s analyzes were clearly influenced by the dynamic concept. In the overall form of the work, Zich distinguished two types: thematic form (which he also referred to as motivic) and dynamic form (force movement), which manifests itself in two basic principles: contrast (the musical stream forms and breaks) and gradation (viewing the music through accumulating tension and its release). The following picture is Zich’s graphic expression of the motivic and dynamic form of the symphonic poem Tábor by Bedřich Smetana. In the upper part of the graph are program headings, in the lower part the course of motivic material; the dynamic graph is complemented by cross-hatching of varying densities, which shows the overall movement of the music. Janeček adopted a similar method of visualization and developed it further in his later analytical writings.

Figure 3: Otakar Zich, Symphonic poems of Smetana, graph of the motivic and dynamic form of the symphonic poem Tábor by Bedřich Smetana

Janeček worked on the book Tectonics from 1964–1966, and with this work he created the theoretical systematics of a de facto new discipline, separated from the science of musical forms. He found inspiration both in Zich’s analyses and, for example, in the opinions of the composer and theorist Leoš Janáček, who distinguished the concepts of the internal and external forms. In the 1950s, when he was writing Musical Forms, he was already well aware that, the analyst must pay attention to the constructive aspects of the work in addition to its formal scheme and distribution of musical ideas. From sonic perception and how the composition is perceived by the listener, he came to the central concepts of musical blocks and tectonic functions. Janeček distinguishes the main functions, which represent the functions of music of an expositional or evolutionary nature. Secondary functions include introductions, intermediate sentences, codes, episodes, and also reminiscences. Form, in the classical sense of the word, is to be understood as structure, distinguishable by the contrast of thematic or tonal material or through applied work of expositional or evolutionary character. Tectonics is a whole work divided into so-called blocks, characterized by immediately perceptible sound properties, i.e., timbre, dynamics, position and pitch of the pedal tone (sound stream), its density, texture, and stratification, kinetic properties, etc. In the sequence and course of the blocks, Janeček addresses their construction, gradations, and descents.

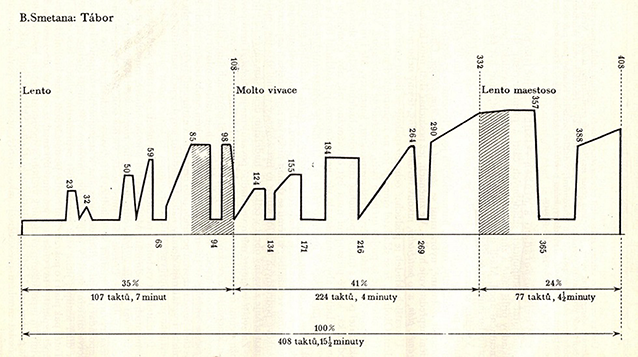

The following example provides a brief comparison with Janeček’s tectonic graph of the same composition (Tábor) in Tektonics, published in 1968. For orientation, here is some basic information about the graph:

• A dynamic line shows the main tectonic blocks; the approximate sound power of the block is expressed by its dimension on the vertical axis.

• The numbers above the curve indicate the measures in which major sound changes occur.

• The horizontal axis indicates the time range, i.e., the sum of the length in cycles and the duration in minutes.

• The sonic peak extends between measures 332 to 357.

• The theme is exposed for the first time in the split vertex in measures 85−98, which is marked by crosshatching the block; the return of the theme is then at the main peak.

• It is clear from the graph that the tectonic center is found in the return of the theme that dominates the whole composition.

Figure 4: Karel Janeček, Tektonics, tectonic graph of the symphonic poem Tábor by Bedřich Smetana

Theoretical writings from the 1940s (Modern Harmony, Counterpoint)

Janeček´s theoretical and pedagogical activities at the Prague Conservatory from 1941 to 1946 were substantially influenced by the presence of Otakar Šín (1881–1943), and by becoming acquainted with Šín´s concepts of music theory in general and harmony in particular. Otakar Šín began teaching at the Prague Conservatory in 1920, at the same time as Janeček became a student. The start of Janeček´s career at the conservatory corresponds to Šín’s decline and eventual death in 1943, and Janeček taught similar courses − harmony, counterpoint, and musical form. We could find similar parallels in their lives and creative contexts, and Janeček described Šín’s position as follows:

Otakar Šín was an excellent theorist whose theoretical discoveries were the result of a compositional-empirical type of musical perception. He was a representative of pedagogical music theory, the main purpose of which was to create working methods for mastering a certain system.[22]

Janeček highly valued his work on harmony Úplná nauka o harmonii (A Complete Theory of Harmony),[23] but he considered it unfinished in the most urgent area − that of modern harmony. The main reason why Šín set about writing on harmony was the fact that he did not find a functional aspect of harmony in the writings of his predecessors. He was critical of Hugo Riemann’s systematics of harmonic phenomena, which he felt was overly complicated and schematic. Riemann’s terminology, the so-called parallels of tonics, subdominants, or dominants (Tp = VI, Sp = II, Dp = III), was interpreted by Otakar Šín as a representative of these main functions (Tz, Sz, Dz). The expansion of dissonances in contemporary harmony challenged Šín to explore their theoretical implications, and he therefore divided them into movement dissonances, the essence of which is harmonic-kinetic tension and the pursuit of divorce, and affective dissonance, the essence of which is the induction of a static emotional affect. Šín’s knowledge of the significance of the metrorhythmic and formal aspects of harmony was absolutely essential for the new systematics of modern harmony. He extended the older system with Phrygian and Lydian chords and thus included all possible chromatic chords. He then crowned his concept with a combination theory – by combining subdominants and dominants with Lydian and Phrygian chords, he could explain all the altered chords of modern harmony.

As a teacher, Janeček was confronted with a new task: namely, that of teaching composition. In this field, he aspired to continue the legacy of his teacher, Vítězslav Novák. As a teacher of composition and theoretical subjects, Janeček focused on the theory of harmony and aspects of modern harmonic devices, a field which was not charted by Šín. For Janeček, the theory of harmony was the most important aspect of the theoretical training of musicians. His previous experience as a teacher had convinced him that teaching through memorization was ineffective. He felt teachers should do more than simply impart knowledge of figured bass. Apart from all this, his Conservatory teaching practice also contributed in setting something of an equal balance between his views of modern and classical harmony.

Since joining the conservatory, Janeček’s theoretical activity followed a targeted and systematic research agenda; the resulting partial studies later became chapters in his first large monograph, Modern Harmony.[24] This is evidenced by the words from the study, in which he briefly characterized the essence of his many years of theoretical research:

I became convinced that the complex problems of modern harmony [...] cannot be solved by occasional studies focused on randomly observed phenomena. [...] I learned that it will be necessary to look broadly, explore the past, and not lose ground. Today, I am glad [...] that out of the unmistakable confusion, an order has emerged that approached the topic with a new idea − finding a way in which it would be possible to classify and characterize the harmony of classical and modern music.[25]

Most studies from the 1930s and 1940s then became partial chapters in the monograph Modern Harmony.[26] The following paragraphs thus represent some of the most interesting passages in Janeček’s systematics of modern harmony.

Janeček began his search for the system by researching harmonic inversion.[27] This switches the old with the new.

Janeček’s studies from the 1930s had already started with this broad view, but at this point he had discovered a phenomenon, that leads to completely new and different sounds in music. Examining the inverse shapes led Janeček to think about their sound quality and degree of dissonance. To express this immeasurable quality, he began to use adjectives such as sharp, irritating, intrusive, and dull; further, he classified harmonic material by key into major, minor, major−minor, and without major–minor. According to Janeček, the inverse relationship between chords is manifested mainly in the ratio of their consonance and dissonance. Janeček formulated the principle of harmonic inversion as follows: “The inversion of a chord is as consonant or has the same degree of dissonance as the original chord.”[28] The inversion of the triad in minor is the triad in major, and they are equally consonant; the inversion of the dominant seventh chord (D7) is a diminished seventh chord (VII7), and they are equally dissonant, etc.

Only in the studies “Harmonické možnosti chromatiky” (Harmonic Possibilities of Chromatic Chords)[29] and “Systém charakteristických akordů” (System of Characteristic Chords)[30] did he work towards a fundamental and final solution of the systematics of harmonic material.

Janeček created a complete summary of all 350 chord types from double sounds (intervals) to twelve notes within the equal-tempered chromatics. The chords are classified into chord classes (according to the number of tones) and into chord types (allowing for adjustments and transpositions). Each chord has its own orientation scheme, which express its interval structure; this can only be determined after the chord is compressed to the smallest extent. For example, the four-note chord c-d-e-g has an orientation scheme 223.

To express the harmonic scheme and dissonant characteristics, Janeček used numbers again to help. He declared the major consonant chords to be a major and minor triad, and based the classification of all dissonant chords on the presence of one or more so-called dissonant elements: semitone (1), whole tone (2), tritone (6) and augmented triad (44 or 0). On this principle, he created four hierarchical levels of so-called dissonant classes − the first contains only one of the dissonant elements, the second contains two dissonant elements, the third contains three dissonant elements, and the fourth contains all four (1,2,6,0).

Counterpoint (1945–1948, unfinished text)

In September 1941, Karel Janeček became a professor of composition and theory at the Prague Conservatory. At this time, the most prominent figure in Czech music theory was Otakar Šín, who had published Nauka o kontrapunktu, imitaci a fuze (Counterpoint, Imitation, and Fugue) in 1936.[31] Until the publication of Šín’s book, all Czech literature on counterpoint was represented by two pedagogically-oriented publications: a half-century-old textbook by F. Z. Skuherský from 1880–1884, and a handbook by Arnošt Kraus and Vojtěch Říhovský from 1921, which, however, did not contain treatises on imitation, canon, and fugue. The lack of works on counterpoint can be explained by the fact that, in the interwar period, Czech music had only two theorists able to write such textbooks, Otakar Šín and Alois Hába; Hába was busy with theoretical reflections on microtonal music. Šín had long been concerned with the issue of harmony, which he felt to be more urgent. Janeček also made every effort to complete his book Základy moderní harmonie (Modern Harmony),[32] and after leaving for the newly founded Academy of Performing Arts in Prague, he did not return to counterpoint; instead, he devoted his other great theoretical work to melody, musical forms, and tectonics.

A characteristic feature of the first Czech writings on counterpoint was the connection to German literature, which, for example, Otakar Šín openly admitted in the introduction to his book, but without specifying which authors and writings he had in mind.

Despite a number of differences, the writings of Skuherský and Šín had one common feature − as composers, they wanted to conceive the issue of counterpoint as a set of compositional rules, but with different degrees of complexity. We can also include Janeček’s Kontrapunkt (Counterpoint) in this line.

Janeček’s unfinished work on counterpoint, which was written between 1945 and 1948, contains 150 typescript pages. The material is divided into 68 chapters, and the first two parts of the general theory of counterpoint and vocal counterpoint are completed. Six introductory chapters from the third part dealing with instrumental counterpoint have been completed. In the text we find several specific references to literature, i.e., to Luigi Cherubini’s counterpoint textbook. [33] Janeček’s broad view of contemporary and older literature and source material is evident from the whole concept of the work and in the surviving drafts, in which the Oxford History of Music[34] from 1932 and other German and Italian publications from the 1930s occupied a leading position in connection with the issue of vocal counterpoint.[35]

His explanation of vocal and instrumental counterpoint relies on a total of 130 examples; of these, Janeček created 116; he adapted and modified 14 examples from the work of Renaissance polyphonists and from fugues by Johann Sebastian Bach. At first glance, it is clear that Janeček’s main concern was to explain the essence of counterpoint and its basic compositional principles − how it is done. Already in his first large work he applied his specific analytical-compositional method, which was to form the methodology of all his major works.

In Janeček’s opinion, the basis for mastering counterpoint and linear thinking was mastering the double voice, and therefore he paid it the most attention. Janeček minimized historical information and proceeded traditionally from simpler to more complex examples − from two voices to polyphony and imitation techniques and the canon. Similarly, in dealing with counterpoint he proceeded from note against note style (1:1) to non-equal counterpoint, to syncopated and, finally, florid counterpoint, the last of which he considered to be ultimate goal of the whole contrapuntal method.[36] Unlike most textbooks, he did not discuss in detail all variants of the ratio of votes, i.e., 1:2, 1:3, 1:4 and 1:6, but only explained the essence of unequal counterpoint and freely combined the mentioned variants in the examples.

Examples that were intended to facilitate the understanding and practical mastery of counterpoint are of three types.

A. Short, one- to two-measure schemes:

• These represent the correct or incorrect movement of voices and the treatment of consonances and dissonances.

• They show correct or incorrect harmonies, cadences (at the end of a harmonic sentence), etc.

B. Longer, comprehensive examples:

• These form separate compositional exercises for a specific type of counterpoint technique in a specific mode.

• In some examples, alternative solutions for difficult passages are presented.

• At the end of individual chapters, Janeček presented and time analyzed several examples representing exemplary compositional solutions.

• A great peculiarity are the examples in which the traditional relations between cantus firmus (c.f.) and counterpoint are mutually exchanged, i.e., the c.f. is composed in shorter values and the subsequently formed counterpoint uses only long values; these solutions are more compositionally demanding and often do not provide a melodically satisfactory result.

C. Examples from the compositions by masters of vocal and instrumental counterpoint:

• These show a masterful mastery of counterpoint and compliance with the rules of strict style and deviations from it and freer treatment of polyphonic invoices.

• By analyzing these examples, Janeček revealed working procedures, e.g., in the composition of canons or complex polyphony.

It is necessary to mention other essential characteristics of all examples:

• They are musically simple, not condensed, and proportional in scope.

• They are composed in basic modes (Dorian, Phrygian, Lydian, Mixolydian, Aeolian) on white keys, with only a few examples in transposition.

• Although these examples of vocal counterpoint represent historically distant modal music, they sound nice. Janeček had a good ear for selecting historical examples that would be pleasing to contemporary listeners.

• They are notated only in modern treble and bass clefs, but Janeček did not deny the need for good knowledge and orientation in scores written in old C clefs.

• Examples of so-called light dissonance, i.e., passages and alternating tones, are consistently circled.

• In most examples, dissonance are indicated by slashes and wavy lines.

• The so-called empty consonances of unison, octave, and fifth are marked with the numbers 1, 5, 8.

• Parallel movement of hidden fifths, octaves, and unisons is denoted by the numbers 5, 8, 1.

• The occurrence of the tritone is indicated in both the melody and in the chords, i.e., in diminished triads.

• Possible tone alterations are indicated by sliders above the notes or sliders in parentheses.

• Bass numbers (5, 6, 6/4, 7, 9) and letters (T, S, D) draw attention in some examples to the harmonic side of polyphony.

Structure of Counterpoint

It is clear from the preserved text that the Counterpoint was to consist of at least three large sections: 1) General theory of counterpoint, 2) Vocal counterpoint, 3) Instrumental counterpoint.

The conceptual peculiarity of Counterpoint is the appearance of a separate theoretical treatise before the chapters. This treatise is entitled “Obecná nauka o kontrapunktu” (General Theory of Counterpoint) and focuses only on specific counterpoint techniques. The first part of the “General Theory of Counterpoint” was to summarize and generalize the postulates valid for any style of Western music, and Janeček emphasized at the outset his emphasis on the practical nature of his book at the expense of a relatively small scope of theoretical material − the general theory of counterpoint actually only gives the technical possibilities of the material.

The influence of Otakar Šín is already indicated by the introductory theoretical postulates, which revolve around a central problem − the relationship between polyphony and harmony. In defining the basic characteristics of counterpoint, Janeček based his approach on Šin’s formulation, but replaced the harmonic element with musical logic: “Counterpoint is a separate melody that forms a coherent and musically logical whole with another simultaneously flowing separate melody.”[37]

According to Janeček, two basic requirements must be met in counterpoint − the melodic independence of the voices and the harmonious integrity of the resulting polyphony. However, the requirements of melodic independence and harmonic integrity are contradictory and complete independence of melodies is not possible − it is influenced by the “harmonic result,” which is most asserted in the cadences. Thus, harmony is not superior to polyphony, although in each polyphonic sentence the harmonic element remains a separate factor. Polyphonic thinking is of a higher degree than “harmonic (homophonic) thinking,” even though it is historically older. Harmonic logic can only be discovered by examining harmonic shapes that arose as necessary by-products in the connection of two or more melodic lines.

Although the independence of melodies varies according to style, it is possible to set general conditions for their necessary contrast. Rhythmic contrast stands out best in a two-voice texture, and the requirement for contrast is met most in mutually syncopated voices. Contrast can be enhanced by metric contrast. Melodic contrast is created by the movement of the voices, which takes place according to the size of the intervals, steps, and jumps, and the voices can proceed by similar and parallel motion, or by oblique and contrary motion; independence can strengthen the crossing of voices and is often associated with differences in dynamics and timbres. The harmonic contrast of voices is related to their latent harmony.

Janeček’s attention to the basic conceptual apparatus led him to differentiate terms: “voice − melody; opposition voice – counterpoint.” In his definition of melody, he referred to the dynamic concept, according to which the essence of melody lies between tones, i.e., in the forces driving the development of melody from one tone to another. A voice is a continuous series of tones that do not necessarily form a melody. In a four-voice texture, the inner voices are usually mere opposites voices that do not form counterpoint. It follows that voice and opposition voices are broader terms than melody and counterpoint − each melody is a voice and each counterpoint is an opposition voice, but the contrary is not always the case.

The remaining passages of “General Theory of Counterpoint” discuss the types of contrapuntal constructions in theoretical terms. Before characterizing them, Janeček reflected on the problem of the constructive nature of polyphony, which he did not perceive as a negative feature − in practical training most works have a technically constructive character, which discourages many students of composition. However, the significance of these contrapuntal exercises also lies in the possibilities of a diverse interpretive concept of polyphonic creation: We can only appreciate all its qualities of technical and musical beauty in an analytical way, by breaking it down into individual components, thus imitating the composer’s actions.[38]

Like Šín, Janeček briefly touched on the history of counterpoint. In its development, he recognized “personal and historical (representative) styles.” According to him, the purpose of the theory of counterpoint was to get acquainted with four historically related representative styles: (1) the a cappella style culminating in Palestrina, (2) the advanced Baroque style culminating in Bach, (3) Classical and Romantic style and (4) modern style. As a modern-minded theorist, he saw his Counterpoint not only in the light of old counterpoint techniques, but also in their application to contemporary music. Even in this section of the interpretation, Janeček did not forget to touch on his fundamental position: “After completing a technical study of counterpoint, it is then easy to penetrate the style in all its breadth and diversity through detailed analyses of contemporary work.“[39]

This historical view of polyphonic music inspired Janeček to consider what was original and unique in the given literature. It concerned the issue of so-called contrapuntal forms, i.e., not only the traditional enumeration and characteristics of musical genres, but also their formal schemes. He mentioned the canon and the fugue as a representative of forms of an explicitly contrapuntal character, because without imitative work they could not be created. However, the term canon does not refer to form, but to a compositional technique. For example, if a melody has a canon in a two-part form, the canon is also two-part or three-part. Longer and clearly divided canons were usually composed of several sub-canons connected to each other, as the following diagram suggests:

Table 1: Karel Janeček, Counterpoint, scheme of a longer canon with sub-canons

However, the form of the larger canon can be solved differently. For example, a canon on the form scheme A – B – A can be repeated at the end of the first canon, or elaborated as a double canon, in which the order of voices is reversed.

Special types of canons whose form results from the compositional technique include infinite and circular canons. In the infinite canon, there is a multiple repetition that affects the vocal part and must be followed by a code. Janeček expressed the scheme of the infinite canon as follows:

Table 2: Karel Janeček, Counterpoint, scheme of the infinite canon

The terms fugue, fughetta, fugato, ricercar, moteto, passacaglia, and ciacona are explained in the “General Theory” only in words, no doubt because Janeček wanted to deal with them in more detail only in the third part on instrumental counterpoint.

The conclusion of the “General Theory of Counterpoint” contains reflections on the most general concepts of polyphony, homophony, and contrapuntal styles. According to Janeček, the polyphonic or homophonic nature of a composition is determined by its overall character, while some works in which polyphony is used in less than half of its content are still considered polyphonic. The seriousness and density of the polyphonic texture is balanced by a larger homophonic area, which always looks more transparent and is easier to perceive by the listener. The relationship of melodies in polyphony can be variable, and some melodic lines can overshadow others with their structural meaning. In non-imitative polyphony, the leading position of a melody is determined by either its melodic quality or motivic structure, i.e., relative melodic value verified by other places in the composition. A truly polyphonic phrase provides in some places several solutions for classifying voices into melodic and less significant ones.

The treatise on “Vocal Counterpoint” forms the second, most complete part of the work. At the beginning, Janeček briefly expressed several starting points and the essence of vocal counterpoint:

• Characters (as in characteristic figures) and compositional techniques are associated with high Renaissance a cappella music and especially with the work of Giovanni Pierluigi da Palestrina.

• The main feature of Renaissance polyphony is horizontal (linear) musical thinking; therefore the study of vocal counterpoint serves as an introduction to contrapuntal thinking in general.

• The treatise on vocal counterpoint includes both (a) the historical-stylistic aspect (i.e., setting norms and rules of a more general nature) and (b) the pedagogical aspect (i.e., arranging the material from simpler to more complex).

• To understand counterpoint, it is better to compose melodies at first, regardless of rhythm; after mastering the basic techniques of two-voice counterpoint, it is useful to add other specific stylistic features of Renaissance polyphony.

After explaining the techniques of counterpoint of equal, unequal, syncopated, and mixed rhythmic values, Janeček discussed the characteristics of free counterpoint in two voices. He really considered it to be the first living compositional technique, in which the free rhythmization of both voices allows a clear distinction of melodic lines. The previous techniques therefore consisted of preparatory work for free counterpoint. In order to bring the practice as close as possible to the technique of the old masters, he required transitions from one mode to another during the counterpoint. Therefore, in this chapter, he included excerpts of Renaissance polyphony among the analyzed examples.

In free counterpoint, the relationship between cantus firmus and counterpoint was balanced − both voices formed freely rhythmic melodies based on the principles of counterpoint in equal, unequal and syncopated rhythmic values. For sections in which other counterpoint techniques are used, Janeček introduced a new concept that he called tact areas. Janeček used the term “tact areas” in connection with syncopated counterpoint. A tact area consists of sections of varying lengths, which can be defined by the following characteristics:

• When using equal counterpoint (1:1), each tone lasts one measure.

• When using unequal counterpoint (1:2, etc.), the longer tone in the upper or lower voice lasts one measure (longer values here represent a whole or half note).

• When using the syncopated counterpoint, the clock area forms tones extended by the ligature into descending delays.

In most Czech textbooks, imitation is discussed as part of instrumental counterpoint. Janeček logically discussed it as part of vocal counterpoint, as most of his examples from the compositions of Renaissance masters were based on imitations. His discussion of imitation thus precedes the extensive and popular topic of canon. In the chapter on imitation and canon, instead of cantus firmus and counterpoint, the concept of so-called proposta and risposta plays an important role. The general introduction briefly explains the commonly occurring types of imitation: strict and free; simple and artificial; and imitation in diminution, augmentation, and inversion. In describing the characteristics of imitation, he emphasized its tectonic function:

Imitation is of great importance in compositional technique because it allows divergence, inherent in the very essence of polyphony, to be mitigated as a unifying element that combines otherwise independently conducted voices into a united whole.[40]

The originality of Janeček’s treatise lies in the distinction between traditional invertible counterpoint and movable counterpoint. While invertible counterpoint is concerned with intervals of an octave or more, movable counterpoint deals with intervals smaller than an octave. Movable is a broader concept than invertible − in movable counterpoint, it is not important to change the order of the voices, because in specific cases they will not be reversed. In invertible counterpoint, the transmission changes the spatial order of the voices.

Janeček defined movable counterpoint as a melody (voice, counterpoint), which melodically and harmonically conforms to the given cantus firmus, both in its original position and in a position shifted up or down by a certain interval. It is thus a kind of melodic transposition, referred to as transposition by the second, the third, the fourth, etc., up to the seventh.

In the composition of this counterpoint, we must avoid those chords that would become inadmissible after the transposition − we must therefore avoid the free onset of dissonances on accented and unaccented beats in a bar. Similarly, we must avoid consonances that would become dissonant upon transposition.

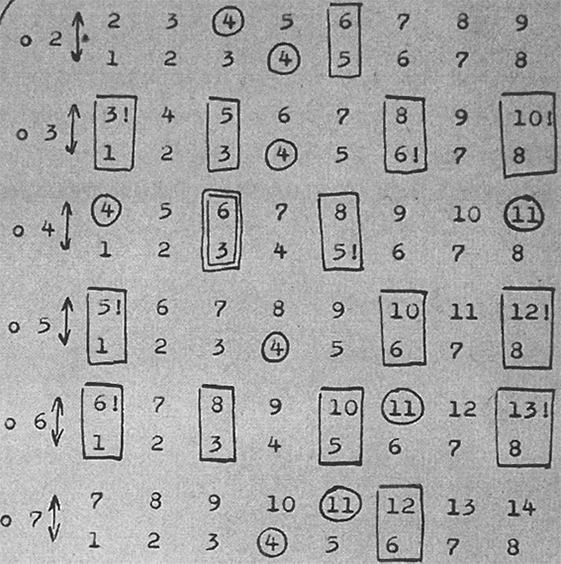

For clarity, Janeček prepared the following table, in which:

• A simple box indicates consonances, one or both of which are empty (1, 5, 8).

• A double box indicates full consonance (3, 6).

• Intervals that are not in the frame must be considered dissonant, as they would be in movable counterpoint, even if they appear consonant.

• Circled fourths and elevenths (4, 11) indicate the possibility of using these intervals if they are added to the sixth chord in the lower voice.

Figure 5: Karel Janeček, Counterpoint, interval transmission table in movable counterpoint

• In movable counterpoint up or down a second, we can freely use only fifths as consonances, while still of course avoiding parallel motion.

• In movable counterpoint at the interval of a third, we are free to use all consonances except the fifth, but still avoiding parallel motion. In the downward direction, sixths become fourths; again one should avoid parallel motion.

• Parallel movement of thirds or sixths can be used only in movable counterpoint at the fourth.

The following musical example is an example of movable counterpoint a sixth below, with the cantus firmus located in the upper voice.

Figure 6: Karel Janeček, Counterpoint, movable counterpoint a sixth below

For comparison, we also present an example of invertible counterpoint in decima and duodecima.

Figure 7: Karel Janeček, Counterpoint, invertible counterpoint in decima and duodecima

Janeček concluded the entire second part of the work, devoted to vocal counterpoint, with a didactic chapter, in which he followed up on the ideas from the first part of the “General Theory of Counterpoint.” The doctrine of vocal counterpoint is a grammar of the old representative style. If we do not deal directly with the work of Palestrina or compositional phenomena close to him, it is necessary to realize that Renaissance vocal work was also influenced by elements of instrumental music, which was necessarily reflected in the structure of the compositions.

Knowledge of the technique of vocal counterpoint is an excellent preparation for the study of the following styles that grew out of it. To understand counterpoint, it is necessary to study the compositions many times; follow the guidance of individual melodic lines and the relationships between them; pay attention to the harmonic aspects of the composition, its division, conclusions, and possibilities of alterative enrichment. After proper preparation in harmony, vocal counterpoint can be practically mastered in half a year. But the purpose of this study is not to acquire a routine, which would then be used for practical polyphonic creation. Rather, the goal is to develop a firm grasp of polyphonic thinking.

As a composer, Janeček believed that contemporary music was overly dependent on harmonic and therefore homophonic processes. Polyphony was a secondary subject in contemporary music, which resulted in the common experience of composition teachers that: “[...] the derivative compositions by untrained students suffer from a complete lack of polyphonic knowledge.”[41]

Modern imitations of Renaissance polyphony can only result in trite commonplaces, not original works. Adequate knowledge of the technique of vocal counterpoint is an essential part of a comprehensive theoretical music education. And the practical mastery of counterpoint is an invaluable preparation for one’s own compositional work; it is, in essence, an exercise in polyphonic thinking, which opens up new horizons for students and provides knowledge that they can use and transform in their own ways in their work.

Janeček completed only six introductory chapters on instrumental counterpoint. He traditionally based his analytical material on the work of Johann Sebastian Bach, specifically fugues from Das Wohltemperierte Klavier. For Janeček, instrumental counterpoint started in the mature Baroque era, and the shift in the development of counterpoint occurred with the development of harmonic thinking, i.e., the style of harmonic homophony.

Janeček divided the regularities of instrumental counterpoint into three working rules:

A. Rules of vocal counterpoint, which could be applied in full to instrumental counterpoint.

These rules were no longer the norm and in instrumental counterpoint they were applied occasionally and only in short passages. This included all vocal counterpoint techniques except for the rules listed in Group B.

B. Rules of vocal counterpoint, which no longer applied in instrumental counterpoint.

These rules had a completely negative meaning and can be summarized in the following theses:

• Instrumental counterpoint was based mainly on major and minor keys; old modal scales had disappeared.

• In instrumental counterpoint, neither voice-crossing nor pauses could be used to disguise parallel unisons, fifths, or octaves.

• Transverse parallels of perfect consonances were not used in the guidance of voices.

• Empty fifths above the tonic were not used at the beginning or end of the phrase.

C. Special rules of instrumental counterpoint that do not apply in vocal counterpoint.

These rules were the most important and were to be the main content of the third unfinished volume of the file.

Conclusion

All Janeček’s major works are characterized by a clear methodological principle: each text is divided into self-enclosed theoretical and practical sections. Their introductory chapters are devoted to theoretical definitions and systematic descriptions of a given phenomenon. These parts are followed by two practically conceived chapters facilitating its understanding and outlining its creative application in analysis and composition. This pattern is exemplified by Základy moderní harmonie (Modern Harmony, analytical practice – compositional practice, 1965), Melodika (Melodics, melodic analysis – compositional goals, 1956), and Hudební formy (Music Forms, composition and analysis, 1955). Another two books, which served an explicitly pedagogical purpose, were conceived along the lines of a specific approach: namely, analysis (Harmonie rozborem [Harmony by Analysis, 1963]), and composition (Skladatelská práce v oblasti klasické harmonie [Compositional Works in the Field of Classical Harmony, 1973]). An exception to this rule was made in Tektonika (Tectonics, 1968), in which he omitted a separate analytical part. Janeček considered the development of compositional and analytical methods to be commensurate with the attainment of the highest level of compositional skill. Paraphrasing the relationship between the two methods, he noted: “[…] having a skill implies being instructed.”[42] An analytical method aiming at the professional level should be as elaborate as possible. Thus it can deal with the ultimate refinements of its matter, including nooks and crannies that are not necessarily within the scope of interest of the compositional method, including the material and characteristic features of marginal styles, unique processes, experiments untested by common practice, and the like. A full comprehension of the analytical method presupposes the intrinsic cohesion of theoretical topics (harmony, counterpoint, forms, etc.), paving the way to understanding the correlations, hierarchies, and general rules defining analytical knowledge. At the same time, the choice of a particular method and its degree of complexity also depends on the type of student to whom it is addressed. The type of individual endowed with an intuitive musicality usually has a tendency towards ignoring the rational aspect of the art, whereas on the contrary, the type characterized by a piercing intellect tends towards relentless problem solving.

Janeček had an instinct for making his books readable, so that they would not only be understandable to composition students. In stylistic terms, his essays took a critical approach to scholarly work. His books remain popular even among non-musical readers and music lovers. In the unfinished Counterpoint, we already find these aspects. Understandable language, logical connections between ideas, the division of the topic into a few focused lessons, and especially the clarity created by the connection between analytical and compositional methods give this document enduring value even after many years.

Janeček saw the meaning of education in the field of counterpoint in two dimensions:

• The first was the methodology of counterpoint for performers. This arose from analysis and from composition itself. An additional goal was to develop acquaintance with contrapuntal thinking and the technical aspects of composition, to facilitate independent study and shape artistic intelligence.

• The second was the counterpoint methodology for composers.

This provided guidance for the creative process and led to an intellectual approach to creative work. Compositional work, even in a modern style, was more important than analysis.

The practical approach is clear from a number of Janeček’s statements that guide the whole text: “In the practical doctrine of counterpoint, almost all the more complex work has a constructive technical character, which discourages many composers from studying it, to their detriment.”[43]

In conclusion, if we are to assess Janeček’s Counterpoint from the point of view of contemporary stimuli and influences, then Šín’s work stood closest to it:

• Both works had a distinctly creative focus, which presupposed a full knowledge of the theory of harmony.

• Both works eliminated the historical approach, which was perceived by contemporary critics as a negative feature.

The basic differences of Janeček’s work can be defined in several basic aspects:

• Janeček based his work on an analytical interpretation from the very beginning, an approach that Šín adopted only in instrumental counterpoint.

• Unlike Šín, Janeček included the issue of double counterpoint, imitation, and canons in the first part of vocal counterpoint, which he demonstrated through specific examples.

Janeček’s work also contains some interesting reflections on the meaning of teaching counterpoint today. From variously scattered considerations, we can reconstruct the following theses:

• The study of vocal counterpoint remains the subject of musicological and theoretical education even today, as it allows a detailed understanding of historical compositional techniques.

• The study of vocal counterpoint makes sense; however, because the historical distance of this music, it is necessary to involve the intellect in its practice.

• The study of vocal counterpoint by composition students increases melodic ingenuity and prevents premature release of creative discipline.

• Knowledge of vocal counterpoint for composers is beneficial, as contemporary music emphasizes polymelodic thinking independent of the harmonic component.

Notes

See Risinger 1959 and 1964, Volek 1959, Jiránek 1972, 1973 and 1986, Hradecký 1967, and Dušek 1966. | |

Ottlová 1980 and Smolka 1995. | |

Risinger 1963. | |

In addition to Czech and Russian, Janeček was fluent in Italian, French, and English. He also had an overview of European musicological literature and sources of music of older stylistic periods, as well as the issue of modern transcriptions. | |

Janeček 1944, 35–36. “Foersterova Nauka o harmonii, byť byla z hlediska pedagogického výtečně sestavena, omezovala se téměř výlučně na základ k vypracování číslovaného basu, zatímco harmonizování melodie věnovala až někde v závěru několik skoupých stránek; ve vlastní teoretické látce přinášela pak předpisy bez hlubšího výkladu podstaty hudebního dění. V celku pak již zestarala natolik, že adeptu skladatelského umění mohla poskytnout oporu jen v nejprimitivnějších otázkách. Zapomenutá příručka Skuherského byla odvážným experimentem, jehož nebylo možno používat jako učebnice. Totéž platí o Úplné nauce o harmonii od Leoše Janáčka.” | |

The text has survived in Janeček´s posthumous papers in the Literary Archive of the Museum of Czech Literature, Litoměřice section, file sign. 631. | |

From Hugo Riemann’s vast body of theoretical work, Janeček cited the following works in his major writings: Riemann 1922b, 1919/29, 1902, 1883, and 1922a. | |

Janeček 1931/32. | |

Ibid., 33. ”Teoretické zásady musí býti demonstrovány na příkladech vybíraných přímo z hudební literatury, neboť jenom přímá souvislost teoretického studia s praktickým pozorováním dává aspoň částečnou záruku u nadaných žáků, že budou harmonickou stránku hudby i po ukončeném studiu sledovati a tím si i nevyspělou dotud představivost vypěstují.” | |

Janeček 1932a. | |

Ibid., 50. “Hrajeme-li melodii nebo sled akordů souvisle (legato), zazní jeden nebo více skutečných tónů v libovolném vertikálním průřezu. Pokud zahrajeme stejnou melodii nebo sekvenci stejných akordů tak, že jednotlivé tóny nebo akordy oddělíme pauzami, tak i během každé pauzy jsou tóny, které zněly těsně předtím - to jsou právě imaginární tóny.” | |

Janeček 1932b. | |

Janeček 1933. | |

Ibid., 164. “Zprvu se zdá, že harmonie má původ v melodii, a to tím, že melodie, vytvořená každým hlasem, stává se jejich spojením harmonií; ale každému z těchto hlasů musila být napřed určena cesta, aby mohly náležitě souznít [...] Tedy harmonie nás vede a nikoli melodie.” | |

Ibid., 165. “Průběžné harmonie se stávaly vzorem pro tvoření nových harmonií základních, tento proces trvá dodnes.” | |

Janeček 1932c. | |

Janeček 1935b. | |

Ibid., 228. “lepkavá žíravina na zdravých kořenech diatonické hudby‛.” | |

Janeček 1935a. See Janeček 1968, Risinger 1998 and 1969. | |

Hutter 1923. | |

Zich 1924. | |

Janeček 1944, 33. “Šín byl vynikající teoretik, jehož objevné teorie byly výsledkem skladatelsko-empirického typu hudebního vnímání. Byl reprezentantem ‚pedagogické‛ hudební teorie, jejíž hlavním smyslem bylo utváření pracovních metod k osvojení určitého systému.” | |

Šín 1942. | |

Janeček 1965. | |

Janeček 1961, 118. “Přesvědčil jsem se, že složité problémy moderní harmonie [...] nelze řešit občasnými studiemi, soustředěnými na nahodile vypozorované jevy [...] Poznal jsem, že bude třeba rozhlédnout se zeširoka, vmyslit se i do minulosti, a přitom neztratit půdu pod nohama. Dnes jsem rád [...], že z nepřehlédnutelného zmatku se vynořil řád spínající staré s novým.” | |

Within the main chapters of Modern Harmony, the following subchapters draw on studies from the 1930s and 1940s: Main chapter I, subchapters “The harmonic scheme of consonances; inversion of consonances; symmetrical and asymmetrical consonance, genera.” Main chapter II, subchapters “Consonances – Dissonances; The principle of harmonic inversion; Dissonance − Characteristics of consonance sounds.” Main chapter V, subchapters “Real and imaginary tones; The meaning of imaginary tones preventing resolution.” | |

Janeček 1943. | |

Janeček 1965, 49. ”Inverze souzvuku je stejně konsonantní nebo má stejnou míru disonantnosti jako souzvuk původní.” | |

Janeček 1947a. | |

Janeček 1947b. | |

Šín 1936. | |

Janeček 1965. | |

Janeček had a translation of Luigi Cherubini’s textbook by the Italian composer, pedagogue, and theorist Luigi Felice Rossi (1805–1863). | |

See Wooldrige 1932. I was able to study the music examples directly from authentic sources, as part of Janeček’s personal library is stored in the music library of the Academy of Performing Arts in Prague. | |

Wolf 1930, Schering 1931, Wagner 1913, Adler 1930, Della Corte 1928. | |

See the basic system of contrapuntal techniques in Fux 1966. | |

Janeček 1945–1948,2. The manuscript has survived in Janeček´s posthumous papers in the Literary Archive of the Museum of Czech Literature, Litoměřice section, file sign. 631. “Kontrapunkt jest samostatná melodie, jež tvoří s jinou současně plynoucí samostatnou melodií souladný a hudebně logický celek.” | |

Ibid., 15. “Všechny její kvality technické i hudební krásy můžeme ocenit teprve analytickou cestou, rozkladem na jednotlivé složky, čímž napodobujeme počínání skladatelovo.” | |

Ibid., 42. “Po skončení technického studia lze pak snadno podrobnými analysemi živé tvorby proniknout do slohu v celé šíři a rozmanitosti.” | |

Janeček 1945–1948, 22. “Imitace má velkou důležitost ve skladebné technice neboť umožňuje, aby rozbíhavost, tkvící v samé podstatě kontrapunktického vícehlasu, byla jí mírněna jako prvkem scelujícím, který slučuje jinak samostatně vedené hlasy v myšlenkově jednolitý celek.”

| |

Ibid., 136. ”[...] napodobivé skladatelské projevy neškolených adeptů trpí naprostým nedostatkem polyfonie.” | |

Janeček 1969. “[…] umět zahrnuje v sobě býti poučen.” | |

Ibid., 15. “V praktické nauce o kontrapunktu téměř veškerá složitější práce má ráz technicky konstruktivní, což mnohé adepty skladatelského umění k jejich vlastní škodě odradí od studia.” |

References

Adler, Guido. 1930. Handbuch der Musikgeschichte, Part 1. Tutzing: Schneider.

Della Corte, Andrea. 1928. Scelta di musiche per lo studio della storia. Milan: Ricordi.

Dušek, Bohumil. 1966. “Janečkovy základy moderní harmonie.” Hudební rozhledy 19/18: 562–563.

Förster, Josef. 1887. Nauka o harmonii. Prague: Cyrillo-Methodějská tiskárna.

Fux, Johann Josef. 1966. Gradus ad Parnassum. A facsimile of the 1725 Vienna edition. New York: Broude.

Hradecký, Emil. 1967. “Janečkova kniha o moderní harmonii.” Hudební věda 4/3: 468–473.

Hutter, Josef. 1923. Bedřich Smetana: Richard III, Valdštýnův tábor, Hakon Jarl. F. A. Urbánek a synové, Prague: Urbánek a synové.

Kresánek, Jozef. 1994. Tektonika. Bratislava: Asco.

Janáček, Leoš. 1912. Úplná nauka o harmonii. Brno: Píša.

Janeček, Karel. 1931/1932. “Rozvoj harmonické představivosti jako otázka pedagogická.” Hudba a škola 4/3, 33–35; 4/4: 58–60.

Janeček, Karel, 1932a. “Moderní harmonie.” Tempo 11/2: 46–52.

Janeček, Karel. 1932b. “O významu imaginárních tónů v harmonii.” Hudební výchova 13/1, 8–9: 22–25.

Janeček, Karel. 1932c. “Třídění harmonického materiálu” (Classification of Harmonic Material). [Unfinished study. Manuscript preserved in Janeček´s posthumous papers in the Literary Archive of the Museum of Czech Literature, Litoměřice section, file sign. 631].

Janeček, Karel. 1933. “Vznik, stavba a ráz nových souzvuků.” Tempo 12/5: 164–172.

Janeček, Karel. 1935a. “Forma a sloh Mé vlasti.” Tempo 14/9–10: 261–275.

Janeček, Karel. 1935b. “Rozvrat diatoniky.” Tempo 14/56: 151–154, 191–195, 227–231.

Janeček, Karel. 1943. “Princip harmonické inverse.” Rytmus 8/5: 54–57.

Janeček, Karel. 1944. Otakar Šín. Prague: Pražská konzervatoř.

Janeček, Karel. 1945–1948. Kontrapunkt (Counterpoint). [Manuscript preserved in Janeček´s posthumous papers in the Literary Archive of the Museum of Czech Literature, Litoměřice section, file sign. 631].

Janeček, Karel. 1947a. “Harmonické možnosti chromatiky.” Rytmus 11/2: 21–23.

Janeček, Karel. 1947b. “Systém charakteristických akordů.” Rytmus 11/3: 66–69.

Janeček, Karel. 1955. Hudební formy. Prague: Státní nakladatelství krásné literatury, hudby a umění.

Janeček, Karel. 1956. Melodika. Prague: Státní nakladatelství krásné literatury, hudby a umění.

Janeček, Karel. 1961. “Harmonický materiál temperované chromatiky.” [Written 1942–1949 (chapter reprinted in Modern Harmony, 19–44)], Hudební věda 4.

Janeček, Karel. 1965. Základy moderní harmonie [Modern Harmony]. Prague: Československá akademie věd.

Janeček, Karel. 1968. Tektonika. Nauka o stavbě skladeb. Prague: Supraphon.

Janeček, Karel. 1969. “Skladatelské stadium.” Hudební rozhledy 22/1: 8–9; 22/4: 105–107.

Jiránek, Jaroslav. 1972. “Smetanovské práce Karla Janečka.” Hudební rozhledy 25/10: 472–473.

Jiránek, Jaroslav. 1973. “Stěžejní teoretický čin Karla Janečka.” Hudební rozhledy 26: 278–281.

Jiránek, Jaroslav. 1986. “Teoretický odkaz Karla Janečka.” Živá hudba 9: 81–96.

Ottlová, Marta. 1980. “Soupis skladatelského a teoretického díla Karla Janečka.” Živá hudba 7: 157–179.

Riemann, Hugo. 1883. Neue Schule der Melodik: Entwurf einer Lehre des Contrapunkts nach einer gänzlich neuen Methode. Hamburg: Grädener & Richter.

Riemann, Hugo. 1902. Große Kompositionslehre 1: Der homophone Satz (Melodielehre und Harmonielehre). Berlin: Spemann.

Riemann, Hugo. 1919/1920. L. van Beethovens sämtliche Klavier-Solo-Sonaten: ästhetische und formal-technische Analyse mit historischen Notizen, I, II, III. Berlin: Hesse.

Riemann, Hugo. 1922a. Grundriß der Kompositionslehre: Musikalische Formenlehre. Berlin: Hesse.

Riemann, Hugo. 1922b. Musik-Lexikon. Edited by Alfred Einstein. Berlin: Hesse.

Risinger, Karel. 1959. “Hudební formy Karla Janečka.” Hudební rozhledy 12/16: 676–678.

Risinger, Karel. 1963. Vůdčí osobnosti české moderní hudební teorie. Prague: Státní hudební vydavatelství.

Risinger, Karel. 1964. “Harmonie rozborem,” Hudební rozhledy 17/17: 747.

Risinger, Karel. 1969. Hierarchie hudebních celků. Prague: Panton.

Risinger, Karel. 1978. Nauka o harmonii XX. století. Prague: Supraphon.

Risinger, Karel. 1998. Nauka o hudební tektonice 20. století. Prague: AMU (Hudební fakulta Akademie múzických umění).

Říhovský, Vojtěch/ Arnošt Kraus. 1921. Nauka o jednoduchém a dvojitém kontrapunktu. Prague: Mojmír Urbánek.

Schering, Arnold. 1931. Geschichte der Musik in Beispielen. Leipzig: Breitkopf & Härtel.

Skuherský, František Zdeněk. 1885. Nauka o harmonii na vědeckém základě ve formě nejjednodušší se zřetelem na mohutný rozvoj harmonie v nejnovější době. Prague: F. A. Urbánek.

Skuherský, František Zdeněk. 1880a. Nauka o hudební kompozici. I. O závěru a modulaci. Prague: F. A. Urbánek.

Skuherský, František Zdeněk. 1880b. Nauka o hudební kompozici. II. O jednoduchém a dvojitém kontrapunktu. Prague: F. A. Urbánek.

Skuherský, František Zdeněk. 1883. Nauka o hudební kompozici. III. O imitaci – o kánonu – o fuze. Prague: F. A. Urbánek.

Skuherský, František Zdeněk. 1884. Nauka o hudební kompozici. IV. O fuze. Prague: F. A. Urbánek.

Smolka, Jaroslav. 1995. Karel Janeček, český skladatel a hudební teoretik. Prague: Academy of Performing Arts in Prague (AMU).

Šín, Otakar. 1936. Nauka o kontrapunktu, imitaci a fuze. Prague: F. A. Urbánek a synové.

Šín, Otakar. 1942. Úplná nauka o harmonii. Prague: Urbánek a synové.

Volek, Jaroslav. 1959. “Karel Janeček − Vyjádření souzvuků. Kapitola ze Základů temperované harmonie,” Hudební rozhledy 12/11: 476.

Wagner, Peter. 1913. Geschichte der Messe 1: bis 1600, Leipzig: Breitkopf & Härtel.

Wolf, Johannes. 1930. Geschichte der Musik 1. Die Entwicklung der Musik bis etwa 1600. Leipzig: Quelle & Meyer.

Wooldridge, Harris Ellis. 1932. The Oxford History of Music. Revised by Percy C. Buck. London: Milford.

Zich, Otakar. 1924. Symfonické básně Smetanovy. (Hudebně estetický rozbor). Prague: Hudební matice Umělecké Besedy.

Academy of Performing Arts in Prague (HAMU)

Dieser Text erscheint im Open Access und ist lizenziert unter einer Creative Commons Namensnennung 4.0 International Lizenz.

This is an open access article licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.