William Earl Caplin, Cadence: A Study of Closure in Tonal Music, New York: Oxford University Press 2024

Tian-Yan Feng

Though cadences are ubiquitous in tonal music, systematic analytical examination of this fundamental musical element remains relatively limited in scholarly literature. William Earl Caplin’s Cadence: A Study of Closure in Tonal Music (hereafter Cadence) addresses this gap by providing a comprehensive exploration of cadential practice and its theoretical complexities.

Caplin’s Cadence presents a systematic theoretical framework for analysing musical closure in tonal music from the common-practice era. The work’s central thesis positions cadence not as mere cessation of sound, but as a sophisticated conventional structure that articulates completion through coordinated melodic, harmonic, and formal procedures. Caplin’s principal objective involves establishing rigorous theoretical criteria for cadential identification, extending his earlier contributions to classical formal analysis. He provides a detailed examination of fundamental cadence types whilst addressing their variations and extensions, drawing primarily upon Classical-period works by Haydn, Mozart, and Beethoven. The theoretical framework subsequently encompasses four chronologically distinct stylistic periods, including Baroque, Galant style, early Romantic, and mid-to-late nineteenth-century repertoires. Caplin contends that cadential understanding remains indispensable for formal analysis, as cadential articulation fundamentally governs musical expression, and shapes listener perception of structural resolution (xiv).

This monograph demonstrates Caplin’s continued engagement with his earlier work, Classical Form,[1] whilst addressing broader scholarly discourse in the field (xviii).[2] As Caplin notes, Classical Form established numerous exemplary cases from the Classical period that generally provide an adequate foundation for basic formal analysis. His new monograph, Cadence, extends this foundation by examining more intricate and sophisticated cadential structures. Caplin recognizes that a comprehensive understanding of cadential function requires detailed consideration of style, including melodic, harmonic, and rhythmic elements, as well as the specific musical language operating within particular historical, geographical, and cultural frameworks. The publication of this monograph thus represents a natural progression from his earlier scholarship, with the two works functioning as complementary contributions to the field.

Caplin’s study develops its entire theoretical framework through the single concept of “cadence.” Drawing upon interdisciplinary approaches including literary criticism (2–4), Caplin demonstrates how temporal art forms share fundamental structural principles governing expectation, continuation, and resolution, with cadential practices serving as the primary mechanism for achieving formal closure in tonal music.

Building upon these interdisciplinary foundations, Caplin consolidates conceptual frameworks proposed by various scholars to systematically establish and explain once more the theoretical foundation for the book’s central focus on cadence, this time in a music-theoretical context. According to Caplin the literature demonstrates a fundamental shift from purely syntactic conceptions of closure towards theoretical frameworks that recognize closure as a multifaceted phenomenon operating simultaneously across harmonic, formal, semantic, and rhetorical domains: Leonard B. Meyer’s foundational work established the crucial repetition/terminal-modification paradigm and distinguished between mere cessation and meaningful closure, whilst subsequent scholars, including Kofi Agawu, Robert Hatten, and Patrick McCreless (5–7), expanded this foundation by demonstrating that effective musical closure emerges from the complex interaction of multiple parameters beyond harmonic resolution alone. Caplin points out, that a persistent theoretical tension pervades the scholarship between temporal conceptions of closure as an “in-time” process of arrival and spatial conceptions of closure as “out-of-time” structural completeness, with Mark Anson-Cartwright’s tripartite model attempting to reconcile these perspectives through simultaneous operation across different temporal scales (8).[3] We learn that the collective scholarship fundamentally challenges the traditional equation of closure with cadence, establishing instead that cadential processes represent merely one mechanism within a broader ecosystem of closure strategies that must be understood holistically.

As previously established, Caplin has addressed the significant theoretical challenge of distinguishing between the conceptual ambiguities and definitional overlaps amongst closure, ending, and cadence, particularly regarding their application within literary discourse and classical music theory. Caplin’s structural organization reveals a sophisticated pedagogical strategy that progresses from theoretical foundations to practical applications across different historical periods, demonstrating the evolution and adaptation of cadential practice within tonal music. The division into two primary parts establishes a methodical approach: Part I (11–302) concentrates exclusively on the classical cadence as the theoretical and analytical foundation, systematically building from general concepts through basic types, deviations, and expansions, whilst Part II (303–582) extends this framework chronologically to examine how cadential practices transformed across different stylistic eras from the High Baroque through the late nineteenth century. This organizational logic reflects Caplin’s theoretical position that the classical cadence represents the normative model upon which all other tonal practices arguably build their developments and variations, placing the Classical period not merely as one historical phase among others, but as a theoretical cornerstone that provides analytical tools and conceptual frameworks for understanding cadential practice across the entire tonal tradition. The progression from morphological description through functional analysis to historical variation demonstrates Caplin’s commitment to complete theoretical coverage, ensuring that readers develop both detailed technical knowledge and a broader historical perspective before encountering the complexities of stylistic deviation and evolution. Most significantly, this structural arrangement reflects Caplin’s theoretical proposition that cadence functions as the primary mechanism of formal closure throughout tonal music, with the systematic treatment of deviations, expansions, and historical variants serving to reinforce rather than undermine the centrality of cadential practice to tonal musical syntax and formal organization.

The author commences his essential exploration of the cadential domain by examining the three most widely recognized types of cadences. Caplin begins with the perfect authentic cadence (PAC), imperfect authentic cadence (IAC), and half cadence (HC), classifying them within two fundamental categories: authentic and half cadences (56–57). His definition of cadences specifies the two primary musical elements that scholars commonly acknowledge: harmony and melody.

What distinguishes Caplin’s harmonic approach, however, is that unlike many general music theory textbooks, he provides a more precise account of how a cadence is approached and prepared. He terms this the concept of cadential stages, or simply stages. From a harmonic perspective, delineating a PAC proves considerably more complex than initially anticipated. Caplin delineates four distinct stages in the cadential progression (57–60): the “initial tonic function” (stage 1), the “pre-dominant function” (stage 2), the “dominant function” (stage 3), and the “final tonic resolution” (stage 4). He stresses – contrary to widespread assumption – that analytical attention to cadence must not be confined to its point of arrival; rather, one must meticulously consider how the music approaches the cadence. Few theoretical studies provide such a constructive account of the preparatory cues that signal the approach of a cadential event, demonstrating that cadences constitute processes rather than mere endpoints.

Caplin’s approach to melodic analysis of cadence (62–78) proves particularly noteworthy in that he extends his examination beyond the soprano line, as is customary in many theoretical texts, to incorporate the alto and tenor voices. His treatment of cadential detail demonstrates remarkable comprehensiveness, employing a broad analytical framework that meticulously addresses the nuances of each voice-leading strand. In this regard, Caplin’s methodology reflects an exceptional degree of precision and attention to detail seldom observed in cadential discourse. This analytical model is applied consistently to other cadential types, including the IAC (82) and the HC, also termed the “semicadence” (101). In his discussion of the half cadence, for instance, Caplin again explains stages 1 through 3: Initial Tonic, Pre-dominant, and arrival on the Dominant (104). This demonstrates how his stage-based analytical framework adapts to different cadential types whilst maintaining its fundamental principles.

The scope of Caplin’s analytical approach becomes immediately apparent. In examining cadences, he extends beyond traditional harmonic and melodic content to incorporate metre (129, including metrically weaker cadences and hypermetrical placement), texture (139, covering textural types and the relationship between texture and cadence), and function – both at the level of phrase functionality and thematic functionality (116). His treatment of the half cadence (HC) exemplifies this comprehensive approach: “The HC is used to close a wide variety of phrase and thematic units, from a simple four-measure antecedent to a highly complex developmental core, one that can stretch to thirty or more measures” (116). Caplin thus seeks to account for the complete range of cadential types across different formal contexts, with particular attention to the duration of the musical unit. Regarding phrase length, he examines cadential behavior in structures including sentential forms, periodic forms, small ternary, and small binary. Concerning thematic function, cadences are analysed in relation to the main theme, transition, subordinate theme, pre-core of the development, core of the development, and early sections of a coda.

However, when analytical objectives prioritize exhaustive coverage of every thematic context, particularly compelling musical moments risk receiving insufficient attention. For example, in Caplin’s discussion of the dual functional levels – phrase and thematic – of the half cadence (HC), he notes, “a transition is characteristically marked by its closing with a half cadence (HC), typically in the newly achieved subordinate key but sometimes in the home key” (119). This topic receives only cursory treatment, addressed in merely a few lines.

Here, one might reasonably expect more sustained discussion of the retransition and its interaction with the HC, particularly given significant analytical precedents in the literature. Roman Ivanovitch’s Mozart study provides a pertinent example: his analysis of the retransition in the second movement of the Piano Concerto in C major, K. 503, where Mozart sustains the dominant chord for nearly a full minute – reportedly the longest such prolongation in his oeuvre – creating intense listener expectation before the main theme’s return.[4] This extended dominant prolongation functions analogously to a half cadence, serving as a moment of heightened anticipation. The passage’s extraordinary quality lies not merely in its harmonic stasis, but in Mozart’s capacity to animate the prolonged dominant through continuous variation in melody, figuration, rhythm, texture, modality, and timbre, thereby producing what might be characterized as the aesthetics of waiting.

This example illuminates a potential limitation within Caplin’s otherwise comprehensive framework: systematic analytical coverage of all thematic contexts may compromise depth in certain critical areas. Ivanovitch’s exploration of the expressive complexity of the retransition, the dramatic function of the extended dominant, and the aesthetic richness of the quasi-HC moment represents precisely the analytical subtlety that proves difficult to accommodate fully within Caplin’s structural taxonomy. This observation raises a broader methodological question: might future scholarship benefit from isolating and examining in greater depth the internal structures and cadential strategies of sonata form? Such an approach could complement Caplin’s foundational contributions whilst addressing the more intricate expressive possibilities that emerge within specific contexts.

This recalls another instance of what might be termed an overambitious analytical project, one in which the aspiration to provide full coverage inadvertently obscures an inherent limitation: that not all phenomena can be explained with equal effectiveness. As previously noted, Caplin allocates considerable space to defining and illustrating each cadence type – its process, structure, and requisite criteria. However, given the considerable breadth of this undertaking, his examination of how specific cadential types operate within particular formal designs or genres frequently lacks analytical depth. Whilst the implications of how individual forms or thematic units tend to favour certain cadential strategies are acknowledged, they are seldom developed with comparable analytical precision.

This limitation became more apparent upon reading Benedict Taylor’s recent and perceptive article, “Closed, Closing, and Close to Closure: The Nineteenth-Century ‘Closing Theme’ Problem as Exemplified in Mendelssohn’s Sonata Practice.”[5] Taylor’s examination of Mendelssohn’s distinctive approach to closing themes illuminates precisely the type of nuanced cadential analysis that Caplin’s framework, despite its systematic rigour, fails to accommodate adequately. Taylor demonstrates how Mendelssohn’s characteristic avoidance of decisive cadential closure and his tendency to reintroduce primary-theme material towards exposition endings create what he terms “apparent C-zones in the absence of an EEC”[6] – a phenomenon that challenges conventional theoretical boundaries. Most significantly, Taylor identifies “a latent terminological ambiguity over whether the word ‘closing’ indicates ‘already closed’ or ‘in the process of closing’”[7] – a distinction that relates directly to one of Caplin’s most valuable theoretical contributions.

Caplin’s insistence on analysing not merely the moment of cadential arrival but the entire trajectory towards closure represents precisely the analytical sophistication required to address Taylor’s terminological concern. However, this strength becomes a limitation when applied to such complex formal contexts as sonata form. Whilst Taylor can trace the subtle interplay between rhetorical and harmonic factors in determining cadential function within specific repertoire, Caplin’s necessarily broad definitional approach, despite its processual insights, allows insufficient opportunity for such contextually sensitive analysis of how different formal designs employ his carefully delineated cadential processes. The result is paradoxical: having developed theoretical tools capable of distinguishing between closure achieved and closure deferred, Caplin provides inadequate space to demonstrate how these distinctions operate within the most cadentially complex of all Classical and Romantic formal designs, making meaningful dialogue between his processual framework and specialized formal studies surprisingly difficult to establish.

However, having established these three fundamental cadence types – and having shown in detail how the PAC, IAC, and HC operate through his stage-based model of harmonic preparation, melodic design, and formal placement – Caplin then advances a more controversial argument: his rejection of contrapuntal and plagal cadences as genuine cadential phenomena, a position grounded in his categorical distinction between prolongational and cadential harmonic progressions.

Caplin’s primary objection to the contrapuntal cadence centres on his strict definition of cadential function. He argues that authentic cadences require root-position dominant and tonic harmonies to achieve the requisite stability and proper bass-line organization necessary for true cadential closure. The contrapuntal cadence, which typically involves inverted dominants (V6, V) or leading-tone harmonies (VII7, VII

), fails to meet these morphological criteria. Crucially, Caplin contends that contrapuntal cadences inhabit “the world of harmonic prolongation” rather than genuine cadential articulation (143). These progressions “propose a potential tonality, but they do not confirm it,” functioning internally within broader thematic processes rather than providing definitive closure (143). He proposes the alternative term “prolongational closure” to distinguish this phenomenon from true cadential function (143). His empirical evidence demonstrates that in Classical style, complete thematic units are rarely closed with such progressions, being instead “generally confined to ending phrases that are internal to broader thematic processes” (143).

Regarding the plagal cadence, Caplin’s dismissal is even more emphatic, describing the disconnect between theory and practice as “perhaps the most egregious” in music-theoretical discourse (146). He argues that “for all practical purposes there is no such thing as a plagal cadence in music of the eighteenth century and the first decade or so of the nineteenth” (146). The fundamental issue lies in the confusion between cadential and postcadential functionalities. When plagal progressions (I-IV-I) appear in Classical repertoire, they almost invariably function as codettas following authentic cadences rather than as independent cadential closures (147). Harmonically, Caplin argues that the plagal progression is “essentially prolongational,” as evidenced by the tonic scale degree held in common between subdominant and tonic harmonies (147). This renders it unsuitable for genuine thematic closure, positioning it instead as a specific type of prolongational closure employing subdominant rather than dominant subordination to the tonic. Through detailed analysis of exceptional cases, including Beethoven’s “Ghost” Trio Op. 70, No. 1, Caplin demonstrates that apparent plagal cadences typically emerge from deceptive cadences that redirect expected authentic closures into postcadential territories, further supporting his argument that these progressions lack genuine cadential function in Classical style.

In the sections that follow, Caplin applies this methodology to two additional cadential types: the evaded (169) and abandoned (178) cadences. He treats each with comparable analytical precision, providing definitions, functional descriptions, and notated examples that demonstrate the cadential process – specifically, how each type is approached and realized within its musical context. Particularly noteworthy is Caplin’s anticipation of broader theoretical issues arising from these cadential types, including cadential ambiguities (209) and cadential expansion (223), which he addresses with considerable analytical rigour. At this point in the text, it becomes apparent that individual musical passages may exhibit multiple, overlapping cadential functions. This creates an increasingly sophisticated understanding of structural and expressive complexity, whereby cadences function not as isolated events but as integrated components within a broader framework of formal articulation.

In the second part of the book, Caplin extends beyond the core composers of the Viennese Classical tradition, shifting his focus to a stylistically segmented discussion organized by historical period. He proceeds chronologically, beginning with the Baroque and Galant styles before advancing through the Romantic and late-Romantic eras, outlining the cadential characteristics particular to each style. Caplin’s primary strategy in this section involves identifying patterns of cadential deviation and exploring prolongational closure – topics that transcend stylistic boundaries and constitute shared concerns throughout the various periods. Only after establishing these commonalities does he focus his discussion on cadence types more closely associated with particular stylistic contexts. In the Romantic era, for instance, Caplin devotes greater attention to issues including chromaticism, dissonance (433), and the increased use of root-position harmonies in cadential contexts (435). The result is a broader framework in which the detailed typology developed in Part I resonates with the stylistic analyses of Part II. The discussion of cadences thus achieves structural and conceptual coherence, linking his definitions with their historical manifestations across a wide stylistic spectrum.

What makes the second part of the book particularly impressive is not only its exploration of cadence within various stylistic periods, but also the systematic and well-curated case studies, which can be viewed as an application of the cadential categories and typologies introduced in Part I. For example, in the discussion of the Baroque era, Caplin focuses on the cadence in fugue, selecting exemplary works from J. S. Bach’s Well-Tempered Clavier and offering in-depth analyses of the fugues in D major (367), E major (370), and G

minor (372), each serving as a detailed case study. For the Romantic period, Caplin turns to Chopin’s Préludes Op. 28 and – remarkably – analyses all twenty-four preludes in their entirety (472–494), a move that reflects both analytical ambition and pedagogical value. Finally, the section titled “Cadence in the Mid- to Late Nineteenth Century” presents four additional case studies that further demonstrate the application of cadential principles in increasingly chromatic and complex harmonic contexts. These later case studies read almost like model classroom demonstrations, making Part II particularly well-suited for pedagogical use, especially in advanced theory or analysis courses.

At this point, we have more or less reviewed and evaluated the overall structure of the book, yet one might begin to wonder: given the scale of Caplin’s ambition, covering cadential types across virtually the entire history of tonal music, is it too much to hope that he might also offer a concise yet insightful account of cadences prior to the Baroque era? As readers who are perhaps equally ambitious, we may expect at least a brief acknowledgement that, before the emergence of functional harmony in the Baroque period, cadences were primarily conceived through melodic motion, with voices moving towards a point of repose, typically resolving on the modal final, or the first scale degree of the mode. Whilst this lies outside Caplin’s stated parameters, recognizing this historical shift would have further contextualized his otherwise comprehensive typology of cadential functions. For instance, one might ask what melodic motion signifies in shaping closure in late fourteenth-century Florentine music, or how the “double leading-tone cadence” found in Machaut’s works foreshadows later developments in cadential practice. Similarly, the music of Binchois and his fifteenth-century contemporaries, the so-called “Landini cadence” is likewise defined by the characteristic movement of melodic lines, whilst even in Palestrina’s sixteenth-century polyphony, whose use of the plagal cadence marks a distinctly modal sense of closure, the sense of finality is again closely tied to melodic shaping. Given these historical precedents, one wonders how Caplin might have further enriched his discussion by drawing clearer connections between these pre-tonal cadential types – based largely on melodic behavior – and the emergence of cadential norms in tonal music. For readers whose ambitions mirror the scope of Caplin’s own project, such contextualization could have offered a more continuous and satisfying narrative of how the expressive function of cadences evolved over time, thereby enhancing the historical depth of this already substantial volume.

Caplin’s insistence on “quadratic syntax” in Classical Form remains contentious. His framework maintains that the four-bar “phrase” forms an inviolable foundation, with presentation phrases never closing cadentially – contradicting traditional theories requiring cadential closure for every phrase.[8] Warren Darcy challenges this premise through Beethoven’s Piano Sonata Op. 2, No. 1, where bars 1–4 (ending on V) lack cadential closure whilst bars 5–8 prolong the tonic.[9] Caplin defends his position by defining “phrase” as a “four-bar group,” a conceptualization that continues to generate scholarly debate.

Given such criticism of his approach to phrase division and cadential function, we must examine whether Caplin’s new publication revises his theoretical position. Preliminary exploration suggests he maintains his stance, though more comprehensively than in Classical Form. In section 2.2.1, Caplin carefully defines the phrase-cadence relationship, drawing upon Janet Schmalfeldt, Ann K. Blombach, Roger Sessions, Fred Lerdahl, and Ray Jackendoff. Echoing Classical Form, he observes: “Cadence and phrase are so intimately connected that the two terms are frequently defined in reference to each other” (16). However, he identifies two problems with conventional understanding: first, some phrase endings are labelled cadences despite lacking proper harmonic criteria; second, “phrase” sometimes encompasses both short groups (4–8 bars) and extensive thematic regions with multiple subgroups (16–17). These critiques enable Caplin to reassert his framework whilst challenging traditional phrase analysis.

Caplin’s framework positions harmony as the principal determinant of formal function, following Arnold Schoenberg’s directive: “Watch the harmony; watch the root progressions; watch the bass line.”[10] However, Floyd K. Grave notes this harmony-centred approach “can limit our analytical purview if it downplays the often prominent role of other elements, including register, dynamics, timbre, surface rhythm, and melodic profile.” [11]

Readers might reasonably expect Cadence to adopt a more multifaceted approach to musical structure and closure, given Caplin’s previous theoretical contributions. This expectation is partially fulfilled. Melodically, Caplin examines alto, tenor, and bass lines systematically alongside the soprano, seeking cadential markers across all registers – demonstrating analytical precision that transcends surface-level observation. Whilst register receives less emphasis than harmony or melody, Caplin acknowledges its significance. Although he maintains that cadential closure operates at the four-bar phrase level rather than in motives or single-bar fragments, he recognizes that “similarities and changes of texture, dynamics, articulation, timbre, register” contribute to our perception of smaller groupings (28). Thus, whilst these elements do not establish cadential function directly, they remain significant to understanding musical structure. This balanced position demonstrates sensitivity to both analytical rigour and the multidimensional nature of musical experience.

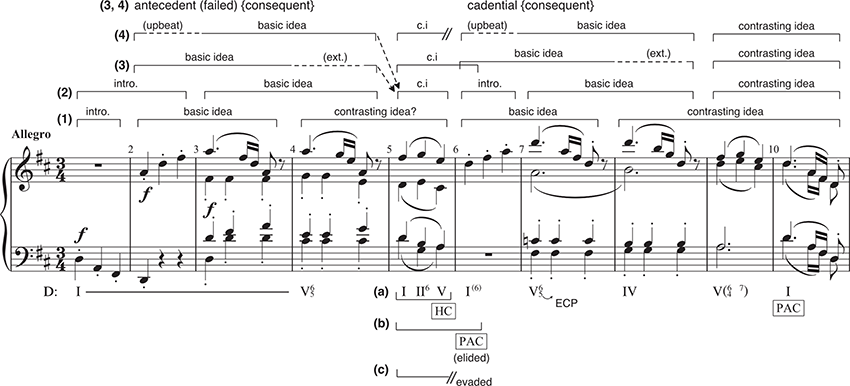

Caplin incorporates rhythmic considerations within his examination of interpretative ambiguities, drawing upon L. Poundie Burstein’s analysis of a Haydn minuet theme to demonstrate how multiple parameters create competing analytical readings (Figure 1, originating from page 220).[12] The opening bars 1–6 yield different interpretations depending on whether bar 1 functions as introduction, bars 1–2 as thematic introduction, or bar 2 as extended upbeat – each producing distinct formal boundaries. Burstein proposed three cadential readings at bars 5–6: half cadence at bar 5’s conclusion, elided PAC at bar 6’s downbeat, or evaded cadence at the same point. Whilst Caplin questions hearing a half cadence on bar 5’s weak third beat, he acknowledges its historical precedent. He favors the evaded cadence interpretation, concluding that the theme’s sophistication lies in sustaining multiple coherent readings simultaneously (220–222).

Figure 1: Multiple analytical interpretations of phrase structure, cadential articulation, and formal function in Haydn’s String Quartet in D major, Op. 71, No. 2, iii, mm. 1–10 (after Burstein’s analytical framework)

Whilst Caplin’s exhaustive treatment of cadential morphology and function represents a significant contribution to music-theoretical discourse, one notes that the monograph does not extensively engage with broader questions relating to musical closure since the late twentieth century, particularly issues of temporality. This represents a potential avenue for further exploration, especially given the author’s detailed examination of cadential practices across multiple style periods, from Baroque to late Romantic, each of which embodies distinct temporal orientations. This opportunity for temporal analysis might be observed in Caplin’s treatment of Baroque cadential practices, where the focus centres primarily on morphological patterns rather than the temporal implications of these structures. Karol Berger’s seminal work Bach’s Cycle, Mozart’s Arrow[13] demonstrates how Johann Sebastian Bach’s cadential procedures reflect fundamentally different conceptions of musical time – cyclical rather than linear, recursive rather than teleological. Berger’s analysis reveals how Bach’s cadences often function as points of return rather than closure, creating what he terms “circular time,” where musical events exist in eternal recurrence rather than irreversible progression. Caplin’s treatment of Bach’s Well-Tempered Clavier fugues, whilst technically accomplished, might have benefited from consideration of how these cadential formations participate in non-linear temporal structures that offer alternatives to conventional notions of beginning, middle, and end.

Similarly, Jonathan Kramer’s influential theorization of musical temporality offers insights that could complement Caplin’s analysis across all the historical periods he examines.[14] Kramer’s distinction between linear and non-linear musical time, where linear time involves goal-directed progression whilst non-linear time creates what he terms “vertical temporality,” could illuminate how different cadential practices generate distinct temporal experiences.[15] The deceptive cadences that Caplin catalogues so thoroughly, for instance, function not merely as harmonic substitutions but as temporal disruptions that challenge linear expectation. Kramer’s concept of “moment time,” where musical sections achieve self-containment without functional dependencies on adjacent material, privileging present-moment awareness over directional progression, could have provided valuable analytical leverage for understanding how certain cadential techniques create temporalities that resist conventional teleological flow.[16] According to Kramer, such moments exist as independent entities that belong to their compositional context through non-linear relationships rather than causal progression, fostering an experience of concentrated present-moment awareness that transcends conventional measured duration. Whilst Kramer primarily applies this concept to twentieth-century composers such as Karlheinz Stockhausen, Igor Stravinsky, and Olivier Messiaen, the underlying temporal principles could illuminate how certain nineteenth-century cadential practices – particularly techniques of evasion and expansion – create moments of temporal suspension that privilege present-moment awareness over directional progression. Such analysis might reveal how specific cadential innovations anticipate the radical temporal disruptions that would later characterize modernist compositional practice.

Moreover, recent scholarship in cultural temporality suggests that cadential practices may reflect broader historical shifts in temporal consciousness. The move from Baroque formulaic closure to Classical teleological drive, and subsequently to Romantic temporal expansion, arguably mirrors larger cultural transitions from cyclical to linear conceptions of historical time. Caplin’s meticulous documentation of these stylistic changes might benefit from engagement with this temporal-cultural framework, particularly in understanding how nineteenth-century composers like Richard Wagner and Franz Liszt employ cadential deferral to create what Carolyn Abbate in her Unsung Voices: Opera and Musical Narrative in the Nineteenth Century[17] terms “narrative suspension” – moments where forward musical motion seems suspended despite the continuation of sound.

The temporal dimensions of cadential function become particularly pronounced when considering how twentieth- and twenty-first-century compositional approaches have fundamentally challenged traditional notions of closure itself. The minimalist procedures of composers such as Steve Reich and Philip Glass, with their employment of additive processes and circular repetitions, suggest alternative models of musical closure merely stopping that question whether conventional cadential structures remain viable analytical categories. Such analysis of how contemporary composers have moved beyond traditional cadential frameworks represents another significant lacuna in Caplin’s study, highlighting temporal territories that remain largely uncharted in cadential theory. This oversight is particularly regrettable given Caplin’s stated ambition to provide a theory of cadential function. Without engaging temporal dimensions, the analysis remains confined to structural description, to the detriment of phenomenological understanding. Future research into musical closure would benefit from synthesizing Caplin’s morphological insights with the rich theoretical resources of temporality studies, generating a more holistic understanding of how cadences function not merely harmonically but as temporal events that shape our fundamental experience of musical time and meaning.

In conclusion, Cadence succeeds admirably as a theoretical textbook, providing educators, students, and researchers with an exceptionally rich collection of analytical examples and methodological frameworks. From the perspective of this review, the volume represents an invaluable contribution to music-theoretical pedagogy and merits a strong recommendation. Caplin’s scholarly ambition in tackling such an expansive topic is commendable, though the very breadth of this undertaking inevitably leaves certain theoretical territories unexplored. One anticipates with considerable interest Caplin’s future contributions to cadential studies, which may well address the comprehensive analytical framework that this foundational work has begun to establish. Fittingly for a study of endings, Cadence closes by opening: it equips us to ask how modern music fashions closure once cadential convention relaxes its hold.

Notes

Caplin 1998. | |

In fact, Cadence builds upon foundations that extend well beyond Classical Form, incorporating insights from Caplin’s earlier scholarship, notably his contribution to What Is a Cadence? – a collection devoted entirely to cadential analysis – and “The Classical Cadence: Conceptions and Misconceptions.” See Neuwirth/Bergé 2015. Caplin also incorporates extensive references to prior scholarship on cadential theory, which are documented in his acknowledgements. | |

Anson-Cartwright 2007. | |

Ivanovitch 2011. | |

Taylor 2024. | |

Ibid., 264. The two terms employed here – “C-zones” and “EEC” – denote the closing zone and the essential expositional closure, respectively, as established by James Hepokoski and Warren Darcy in Elements of Sonata Theory. See Hepokoski and Darcy 2006, xxv–xxvi. | |

Ibid., 263. | |

Caplin 1998, 45. In brief, Caplin acknowledges that traditional theories typically assume every phrase must conclude with a cadence. However, he maintains that the “presentation phrase” within a sentence “in principle, never closes with a cadence.” This assertion has subsequently drawn challenges from several theorists, including Warren Darcy. | |

Darcy 2000, 123. Darcy’s analysis reveals that bars 1–4, ending on the first inversion of the dominant seventh, do not constitute a half cadence, whilst bars 5–8 form part of a tonic-prolongational progression. This reading directly contradicts Caplin’s requirement for phrase boundaries at four-bar intervals, as the harmonic structure suggests a different grouping structure altogether. | |

Caplin 1998, 2. | |

Grave 1998. | |

Burstein 2014, 212. | |

Berger 2007. | |

Kramer 1988. | |

For comprehensive discussion of linear and non-linear musical time, including instances where these temporal modes intersect, see Kramer 1988, 20–65. | |

For extensive analysis of moment form, see Kramer 1988, 50–62 and 201–212. | |

Abbate 1996. |

References

Abbate, Carolyn. 1996. Unsung Voices: Opera and Musical Narrative in the Nineteenth Century. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

Anson-Cartwright, Mark. 2007. “Concepts of Closure in Tonal Music: A Critical Study.” Theory and Practice 32: 1–17.

Berger, Karol. 2007. Bach’s Cycle, Mozart’s Arrow: An Essay on the Origins of Musical Modernity. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Burstein, L. Poundie. 2014. “The Half Cadence and Other Such Slippery Events.” Music Theory Spectrum 36/2: 203–227.

Caplin, William Earl. 1998. Classical Form: A Theory of Formal Functions for the Instrumental Music of Haydn, Mozart, and Beethoven. New York: Oxford University Press.

Darcy, Warren. 2000. “Reviewed Work(s): Classical Form: A Theory of Formal Functions for the Instrumental Music of Haydn, Mozart, and Beethoven.” Music Theory Spectrum 22/1: 122–125.

Grave, Floyd Kersey. 1998. “Book Review: ‘Classical Form: A Theory of Formal Functions for the Instrumental Music of Haydn, Mozart, and Beethoven,’ by William E. Caplin.” Music Theory Online 4/6.

Ivanovitch, Roman. 2011. “Mozart’s Art of Retransition.” Music Analysis 30/1: 1–36.

Kramer, Jonathan D. 1988. The Time of Music: New Meanings, New Temporalities, New Listening Strategies. New York: Schirmer Books.

Neuwirth, Markus / Pieter Bergé, eds. 2015. What Is a Cadence? Theoretical and Analytical Perspectives on Cadences in the Classical Repertoire. Belgium: Leuven University Press.

Taylor, Benedict. 2024. “Closed, Closing, and Close to Closure: The 19th-Century ‘Closing Theme’ Problem as Exemplified in Mendelssohn’s Sonata Practice.” Music Theory Spectrum 46/2: 263–287.

Dieser Text erscheint im Open Access und ist lizenziert unter einer Creative Commons Namensnennung 4.0 International Lizenz.

This is an open access article licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.