An Uncertain Perception

Notation in the Age of Human-Computer Interaction

Benjamin K. Bacon

This article surveys the intertwined nature of contemporary notation practices and ideas from the field of human-computer interaction. Current approaches towards notating music are in a phase of divergent exploration, embracing a wide variety of technical and artistic interpretations using combinations of new technologies and graphic display techniques. Each application yields within itself an array of potential choices which can then greatly impact the abilities of the reader to clearly interpret what the score, and more importantly the composer, is trying to communicate. By tracing recent approaches in notation design practices through the lens of human-computer interaction, we can locate where creative opportunities appear as well as where important trade-offs are being made, and which frameworks for composing result from the integration of interactive design thinking with the notation itself.

Der Beitrag untersucht Zusammenhänge zwischen zeitgenössischen Notationspraktiken und Ideen aus dem Bereich der Mensch-Computer-Interaktion. Gegenwärtige Ansätze zur Notation von Musik werden aus unterschiedlichen Perspektiven erörtert und dabei technische wie künstlerische Überlegungen, die von der Kombination neuer Technologien und grafischer Darstellungsmöglichkeiten angestoßen werden, einbezogen. Jeder Notationsansatz impliziert Entscheidungen aus einer Reihe von Möglichkeiten, die sich erheblich auf die Auffassung dessen, was das Notat vermitteln soll, auswirken können. In der Betrachtung jüngerer Ansätze zu Fragen der Notation aus Perspektive der Mensch-Computer-Interaktion werden kreative Spielräume wie auch einzugehende Kompromisse ausgelotet, um zugleich aufzuzeigen, welche Rahmenbedingungen für das Komponieren gelten, wenn Denkansätze aus dem Bereich interaktiven Designs mit der Notation zusammengeführt werden.

Follow the Score

Perhaps it comes as no surprise to those engaged with contemporary music notation and scoring practices to observe that we are currently moving steadily—if not accelerating—along a path of divergent strategies driven by technological change. Creative programming tools, such as Max,[1] exemplify this trend, continuously expanding notational capabilities through advancements in graphical processing and specialized notation-focused libraries for advanced interactive scoring.[2] In the academic discourse, offshoots from human-computer interaction (HCI) research venues, such as the leading annual CHI Conference,[3] have split off, now forming musically focused companions such as the NIME Conference[4] (focused on musical instruments), and most recently the TENOR Conferences,[5] which specifically focus on music notation and representation. These communities have driven forward critical discussions about what it means to notate in the twenty-first century, while offering a platform for emerging technologies, including their application in new creative works.

While each of the aforementioned institutions offers ample space for participating in and observing new trends in contemporary music notation and scoring practices, the online organization Score Follower[6] stands as a unique focal point specializing in the presentation of contemporary scores synchronized with their own music. Due to their open submission approach and independence from academia (although they maintain many partnerships), the Score Follower catalogue cuts across the academic, festival, and independent artist landscapes, offering a unique snapshot of modern-day notation practices. This is further bolstered by its self-proclaimed mission to diversify and provide access to a field of music that has historically been confined to predominantly academic spaces. Spread across several social media platforms (YouTube, Instagram, Discord, etc.), Score Follower has emerged as one of the few community-driven archives of contemporary music of the past decade. The most visible public-facing entity of Score Follower is its YouTube page, where one can view over one thousand videos of synchronized scores and music. While the oldest videos were created several years ago, the Score Follower YouTube-catalogue contains many pieces written as far back as the early 2000s, with a few pieces written in the 1990s. The majority of Score Follower’s collection, though, consists of pieces posted within one year of being written,[7] rendering their library particularly representative of present-day trends in notational and other representational strategies. By simply scrolling through and observing the past eight years of uploads, these trends become visible, as the thumbnails evolve from predominantly displaying the traditional black and white scatter of noteheads, staff lines, and clefs, to including gradually more and more colorful bursts of contoured lines, strange glyphs, and graphics, which seem to appear more like user interfaces rather than music notation.

The various changes occurring across the compositional landscape are made apparent by Score Follower, even over such a short span of musical history. This sentiment is not lost on the curators themselves. By scrolling further down the “call for scores” on their 2024 season webpage, a FAQesque conversation between Score Follower and a hypothetical—and somewhat reluctant—composer appears. Score Follower’s own FAQ shows that although the word “score” is in their name, the very term itself is in a period of flux. After just a few words, the discussion reveals how the very boundaries of what does or does not qualify as a score exist as a concern for many young composers:

YOU: I want to submit my piece to follow my score but there’s not really a score to it; it’s more like a list of instructions

SF: It’s cool, we do that ➝ https://youtu.be/zghFcRt7C54

[example of an instruction-based piece with minimal or no traditional notation]

YOU: Yeah, but there’s like video footage too

SF: Yeah I mean we do that too ➝ https://youtu.be/qyB97pqyR40

[integrates performance video as part of the score experience]

YOU: OK! but I’m worried because the instructions are asynchronous

SF: Umm, have you seen our vid of Jennifer Walshe’s EVERYTHING YOU OWN HAS BEEN TAKEN TO A DEPOT SOMEWHERE? ➝ https://youtu.be/ZgZfD3JogT8

[multilayered, performative score using text and voice in asynchronous form]

YOU: WOAH, ok I’ll send my piece! For the second piece I’m thinking of submitting, it’s already audio-visual format.

SF: FAB! We love featuring non-static visual mediums AS the score itself… like this ➝ https://youtu.be/kh1pVXVLTB4 and this ➝ https://youtu.be/zpc-2cVliCk

[score rendered entirely through animation] [real-time generated visuals as notation]

YOU: NICE, but it’s more like a video game

SF: boom ➝ https://youtu.be/_wScl3xKZxo

[interactive, game-based environment acting as the score]

YOU: oh wow, but the video game isn’t really a score, it’s just like I built this interactive instrument, and I kinda just want to show that

SF: Oh like this ➝ https://youtu.be/NgBU6ASE-Cw

[instrument demonstration presented through an interactive interface with gestural mappings][8]

Figure 1: A screenshot of Score Follower’s YouTube page showcasing their emphasis on novel notation design in contemporary music[9]

The uncertainties of the fictive composer in this exchange (which continues further) on Score Follower’s website reflect a wider sense of questioning currently occurring within music compositional circles. A closer reading also indicates how central technological change, including its opportunities, drives the conversation. From the computer music side of the discussion, the questioning of notation’s role can be even more blunt. For example, in a February 2025 call for papers addressing notation for electro-acoustic music, the journal Organised Sound asked: “Given the consensus amongst many electronic musicians that common practice notation […] is no longer fit for purpose, what is?”[10]

Questioning the function of traditional notation within the score, or what even qualifies as a score, is a trend emblematic of the digital age. Within library and archival sciences, fields specifically concerned with the organization and cataloguing of creative human artifacts, critical inquiries into what defines a particular media format, including its categorization and preservation, remain central topics of research and discussion as well.[11] In many ways, Score Follower’s status as a de facto community archive of recently notated music, situates them uniquely within this problem space. Fortunately, one may find some inspiration in confronting these challenges by examining the terminology used by the fictitious composer in the aforementioned FAQ discussion. While notions of “asynchronous instructions” and “audio-visual formats” are uncommon in textbooks of traditional music theory, they do reflect the language of software developers, interaction designers, and digital instrument builders—a vocabulary rooted in the multidisciplinary field of human-computer interaction (HCI).

The Instrumental Blackbox

The modern field of what we now consider HCI has many roots, stemming from computer science, engineering, cognitive and behavioral sciences, oriented around the study of ergonomics and human factors, and reaching its modern form in the early 1980s.[12] In other words, HCI is focused on how computational systems and environments can be designed to enhance human well-being, safety, and performance by aligning them with our behavioral and perceptual capabilities and limitations. This also includes how creativity can be bolstered by technology, which falls specifically within the performance context. Of course, when it comes to music, electronic or computational technology has long been a subject of intense interest from a creative standpoint, and HCI-led research has been a key component in developing numerous centers for interdisciplinary research (e. g., IRCAM in Paris, CIRMMT in Montreal [13]) around the world dedicated towards enhancing our understanding of how systems of interaction in music can be developed, from new instruments to sound synthesis and spatialization methods.

Within the first decade of the post-war period, Karlheinz Stockhausen’s Studie II (1954) demonstrated how the parameters of electronic sound could be notated so that a work could be reconstructed in the studio. Likewise, Rainer Wehinger’s 1970 listening score for György Ligeti’s Artikulation (1958) mapped perceived timbral events to precisely timed color symbols, revealing the finer details of the work’s sonic architecture. These early examples model the explanatory power of well-designed graphics when the complexities of visual form and musical information work in harmony. Yet, given the breakneck speed of technological breakthroughs, there remains a broad sense in wider society that the speed with which we are integrating these new tools for our performative capabilities is outpacing our ability to understand the way in which we are affected by them. Thus, the predicament voiced by the unnamed protagonist in the Score Follower FAQ is perhaps met with some empathy.

The burgeoning sense of uncertainty regarding the way forward for notation in compositional circles has not slipped under the radar, particularly within HCI’s musical frontier, otherwise known as music technology. Thor Magnusson offers a framework for understanding the relationship between instruments, scores, and their performers in his book Sonic Writing.[14] Here, he argues that the very definitions we use to describe our work, including the values which imbue our creative practices with meaning, are deeply shaped by technological interaction as musical epistemes.[15] In this case, each episteme constitutes a larger period of musical history where the music-making tools at our disposal largely influence what we claim to express in the music itself.

Using the nineteenth-, twentieth-, and twenty-first centuries as historical touchpoints, Magnusson addresses these periods as marked by acoustic, electronic, and digital technologies. The episteme of the nineteenth century was formed by the wide-scale standardization of acoustic musical instruments and the ocular centrism of their performance behavior (one can clearly see how they work).[16] In terms of Peircean-semiotics[17], acoustic instruments are iconic in that their interface and sound source are one in the same. The depiction of a cello represents its sound, as the body of the instrument is what physically produces what we hear. In the twentieth century, electronic instruments furthered a kind of relationship which can be seen as indexical. There are certain forms of connection visible between sound source and sound production.[18] For example, moving a fader up on an analog piece of hardware will generally increase the signal’s strength; an intuitive interaction governed by the principles of electrical engineering. The current and most recent episteme guiding the instrumental practices of the twenty-first century is tied to the blackbox that is digital technology. Despite the fact that one could theoretically “know” how each step functions in the chain reaction of processes triggered when a digital musical instrument is performed, it is impossible to verify through direct observation. One popular digital musical instrument known as the “T-Stick” (Figure 2), is quite ambiguous in shape and could resemble from afar any number of cylindrically shaped acoustic instruments, but the sounds it produces are completely separated from the controlling device.[19] A T-Stick could equally sound as close to a bassoon as it could to a rainstick, or even to something in between, further emphasizing how our current episteme is defined by the disconnect between sound and gesture, instrument and performer.

Figure 2: The “T-Stick” digital musical instrument developed by Joe Malloch[20]

When it comes to composing in a time where technology is blurring long-held lines of thinking, Magnusson makes a few suggestions as to where we are headed. This includes the embracing of live-coding and animated-scores as new forms of notating a composition, where he warns that composers will need to become comfortable with the dissolving boundaries of traditional composer-performer relationships.[21] As such, composing for digital instruments in particular presents a unique problem space for understanding the role of notation going forward. As opposed to “idiomatic”[22] scoring for new instruments (i. e., developing a notation to suit the specifics of an instrumental design), the concept of “supra-instrumental” interaction is posited by Magnusson as another compositional strategy towards developing a notation system. In this way, composers write for a wider scope of musical interactions aiming to speak beyond the fast-approaching waves of innovation and obsolescence which often envelop electronic and digital musical instruments. Supra-instrumental composition is predicated on ergotic gesture, where “forces, displacements, exchanges of energy between a human body and material objects or a material environment” take place.[23] Supra-instrumental interaction allows us to essentially zoom out and view the relationships between body and object as a continuous energetic exchange. Such a perspective can serve as a map for the abstraction and ultimately transposition of interaction between real and virtual spaces. Theoretically, a controller capable of reproducing similar multi-sensory feedback (e. g., haptic, audio-visual) can access the gestural knowledge of the performer, and in such cases, instrumental skill can be transferred to new input devices and synthesis engines.[24]

Magnusson’s exploration of supra-instrumental composition delves into broader gestural and behavioral aspects inherent in a musical performance, yet this approach suggests a potential trade-off: sacrificing instrumental specificity for conceptual longevity. On the other hand, Claude Cadoz describes the supra-instrumental concept as a pathway to achieving a kind of “absolute writing,”[25] wherein a composition’s notation would encapsulate an instrument’s physical attributes, gestures, sounds, and behaviors. This perspective hints at a more granular form of compositional specificity, perhaps tracking closer towards designing notations which would satisfy American philosopher Nelson Goodman’s controversial theory of an authentic representation of a creative work.[26] These dual interpretations of supra-instrumental composition underscore a tension between abstraction and specificity. With the evolving landscape of electronic instruments (digital and analog) and their fluid control mappings, it becomes evident, as Magnusson observes, that integrating technology, notation, and performance will inevitably entail friction. Concurrently, many composers, as evidenced by Score Follower, are embracing new technologies in their compositional and notational methodologies. While these innovations promise exciting creative prospects, an HCI perspective urges careful consideration of the potential trade-offs involved. Essentially, the act of design inherently intertwines with the act of critique, reminding us to approach technological integration with a mindful eye. Filtering our decision-making processes in developing any new notational strategy can be quite daunting. Overlapping dependencies and a massive range of creative opportunities make the matter no simpler. Fortunately, though, the analytical lens of interface and user-interaction design—another important subset of HCI—offer important lessons for us to observe.

Locating Trade-Offs

In his examination of music creation within the digital audio workstation environment, musicologist Michael Anthony D’Errico describes the challenges of “technological maximalism” in music technology, where the cumulative nature of options presented in software can overwhelm our ability to navigate it.[27] This in turn leads to a “crisis of the control surface,”[28] leading many to adopt self-imposed limits in order to clarify any available options and reconstitute a sense of creative agency. This phenomenon is evident in digital audio workstations (DAWs), which are becoming an increasingly important part of many composers’ creative toolkits. Applications which had once started out as simple multi-track editing platforms, have since evolved into fully fledged generative musical ecosystems, often laced with legacy interface components which act as reminders of the software’s functional origins. Once more, as many DAWs now follow aggressive release cycles, new features and capabilities are constantly announced as a lure to upgrade. Ableton’s[29] software capabilities have become so extensive—particularly with the integration of the Max programming language—that they offer a book dedicated to helping newcomers navigate the wide array of creative choices for creating electronic music.[30] Through rapidly advancing technology, one of the major challenges facing composers is not only how to represent their music in notational form but also how to create it in the first place. Navigating these creative expanses can be quite difficult, especially as the guiding clarity of simple, intelligible limitations can become lost. This can lead to a musical form of the fictional game known as “Calvinball,” where the constant opportunity to rewrite the proverbial rulebook feels as though there is no rulebook at all.[31] The DAW example illustrates how new notation systems can be potentially strained in a similar fashion by technological maximalism. The limitless number of representational options, whether through virtual reality headsets, animation, or artificial intelligence augmentation, further burdens the designer (i. e., composer, notator, and/or performer) with endless options.

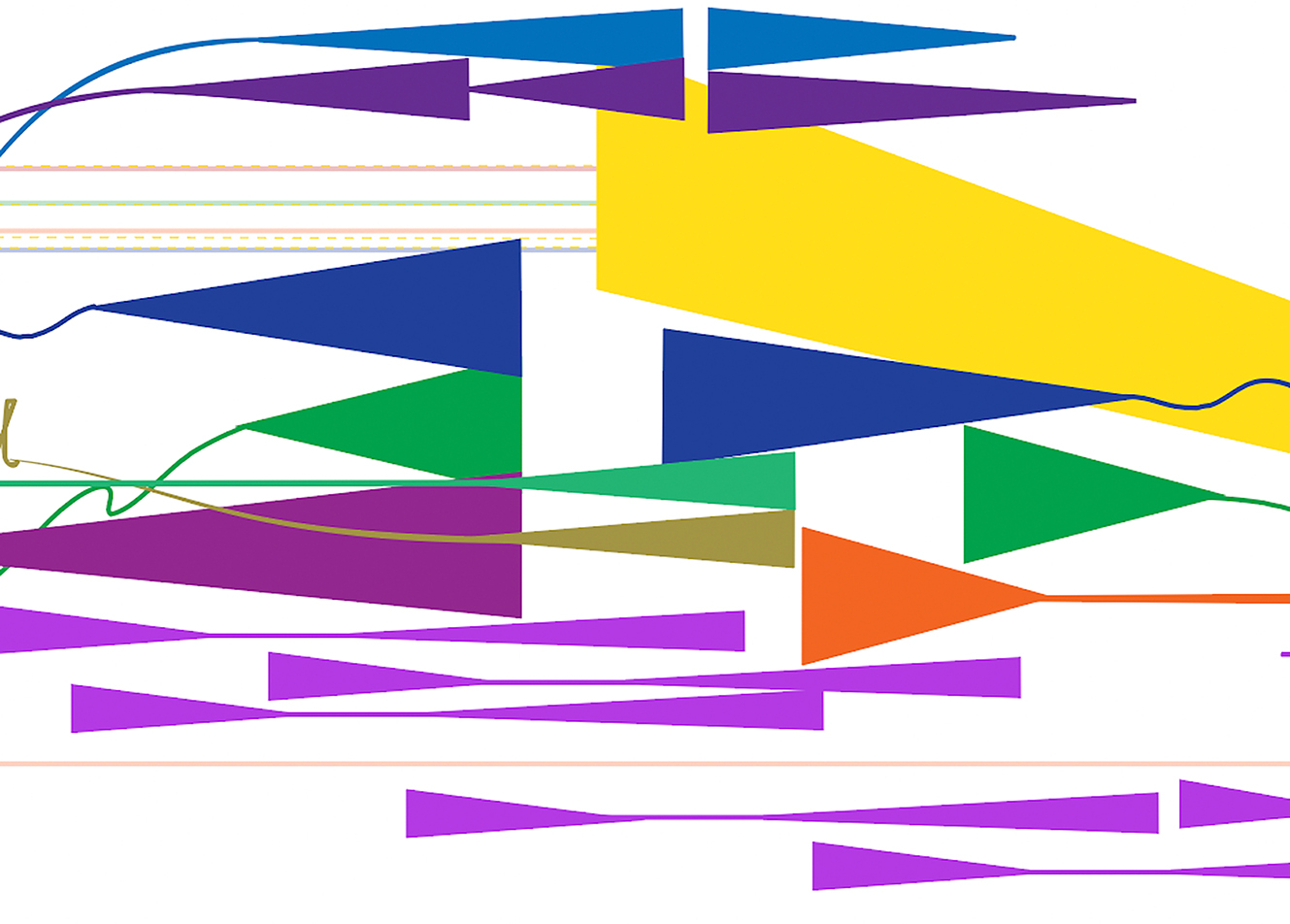

Australian composer Catherine Anne “Cat” Hope (born 1966) manages to capture the mood of many composers interested in augmenting their scores with technology. In an article for the Computer Music Journal,[32] Hope elaborates on the opportunities presented by bringing scores to life with movement. The ability to map musical instruction across the visible trajectory of a notation offers novel forms of interplay between the performer and score, including new approaches to aleatoricism and spatialization. For example, the dynamic spatial relationships between entities in a score can be depicted by animating their precise trajectories, thereby making the specific behavioral patterns visible to the performer. For composers like Hope, the creative opportunities offered by new technology are primarily seen as tools for communication. While this intention seems straightforward from a compositional standpoint, it sometimes includes variations in how other forms of information are presented. Hope articulates that although her scores are meticulously crafted with the express purpose of “transmitting musical information”, she also makes deliberate choices about the notation’s appearance that “are not driven by any sonic imperative, such as the colors” she chooses.[33] Considerations such as these often surface when a composer develops new notational systems, raising the question of how aesthetic aims and functional requirements can be brought together. In Hope’s 2018 piece Speechless (Figure 3), the selected color palette balances vivid primary hues that produce a visual field with contrasts that help distinguish instrumental groups. Such decisions are undoubtedly within the composer’s prerogative and carry their own weight relating to the expressive elements of the score. Yet, when viewed through a perceptual lens, as is common in HCI practice, it may be worth exploring the role of color more closely given its role in conveying visual information. Human-computer interaction design principles can provide useful lessons for creatively applying color within visual displays, allowing it to serve both aesthetic and instructional purposes concurrently. This perspective underscores the unique opportunities which present themselves when visual-perceptual elements are integrated into the creative compositional process.

Figure 3: Catherine Anne “Cat” Hope, Speechless (2018), animated graphic score (excerpt)[34]

In response to a famous quote by the painter Paul Klee, “To paint well is simply this: to put the right color in the right place,” the information design theorist Edward Tufte describes the proper use of color as a task of immense complexity.[35] So much so in fact, that Tufte’s first principle of working with color is “above all, do no harm.”[36] By this, he argues that the indiscriminate use of color can interfere with the ability of others to properly interpret information graphics. For example, starkly adjacent colors can, at times, trigger simultaneous color contrast effects, producing shifts in perceived hue even when those colors were chosen to increase visual clarity.[37] Producing visual clutter, or what Tufte has coined as “chart junk,”[38] can happen when dressing-up information with superfluous graphics. As a result, the primary meaning of what is shown is hindered in the service of aesthetic considerations. Color carries considerable weight given its status as a primary category of visual perception, and thus, needs to be carefully applied, especially when conveying conceptual information. Composers are always at liberty to use color in their compositions as guided by their inspiration, but they might also gain a valuable new communication tool by incorporating insights about principles of human perception in the design and application of new notational systems.

Cognitive dimensions

A clear way of judging a design choice within a given score is to ask how much information the performer needs to process. A team of human-computer interaction researchers led by Alan Blackwell has developed a system of evaluation for notation systems known as “cognitive dimensions,” which allows for more transparency in determining the strengths and weaknesses of a given design structure.[39] The primary goal of the cognitive dimension framework is to provide designers with a more robust vocabulary of descriptors for evaluating a notational system’s complexity and flexibility. Concepts such as “role expressiveness,” and “hidden-dependencies” allow for the gauging of a system’s taxation on the user to navigate its structure. Role expressiveness helps describe the ease by which one could understand “why the programmer or composer has built the structure in a particular way,”[40] while hidden-dependencies can help illuminate unseen chains of dependencies between entities in order to avoid any “unexpected repercussions”[41] within the system. Figure 4 supports this discussion by mapping traditional music notation through an “Entity-Relationship Modelling for Information Artifacts” (ERIMA) diagram,[42] exposing the system’s underlying structural assumptions and the cognitive load they generate. By visualizing how even the most familiar notational elements are anchored in a dense web of implicit relationships, the diagram grounds the need for cognitive dimensions as an evaluative tool capable of revealing where such complexity becomes burdensome for users.

An important aspect of the cognitive dimensions is that they are each designed to direct the attention of the system designer to the perceptual bandwidth of the user, while also suggesting “maneuvers” by which the system could be altered for more efficient use. Unfortunately, no particular list of corrective instructions can be prescribed for a given predicament, as the diversity of different notational systems is too broad for any evaluative framework to offer case-specific advice. Rather, the cognitive dimensions framework was created specifically to highlight behavioral characteristics of a notation which are known to be the root of unintended confusion upon interaction.

Figure 4: An example of “Entity-Relationship Modelling for Information Artifacts” (ERMIA) applied to western music notation, illustrating the cost of change through its interrelated dependencies[43]

One could criticize a framework like the cognitive dimensions for attempting to appeal too broadly in its utility. By engaging with it, music notation (especially of the experimental variety) is evaluated alongside information processing environments. This harkens back to the analytical approaches of human-factors research of the 1970s, an age where systems were optimized to increase output, regardless of user creative agency. Systems like this are known as being part of the “second paradigm” or “wave” of HCI, where interaction is framed squarely in terms of efficiently designed communication pathways.[44] Design thinking within this framework gravitates towards reducing errors and streamlining complex processes. When it comes to writing music, these concepts tend to produce feelings of discordance. It cannot be disregarded that notations may contain an aesthetic of their own, especially relating to the way in which Cat Hope explained her compositional methodology; not every graphic component of a notation is chosen solely for its functionality. Novel notation systems, including those augmented by new technology or those containing completely new graphic representational structures, must be able to strike a balance between art and science. Edward Tufte’s approach in designing information displays emphasizes the importance of revealing the natural aesthetics found in the information itself. The patterns made visible to the interpreter by a notation are themselves a source of profound beauty and elegance. Even the concept of narrative as Tufte demonstrates in his book Visual Explanations, is something which information graphics present quite powerfully.[45] Perhaps it is here, nestled within the forces of subjective perception and quantitative science, that we may ultimately find a sense of clarity for the direction of written music within the digital episteme.

Hybridization of Notation

In an analysis of the relationships and reciprocating influences of music and the visual arts, Simon Shaw-Miller focuses on the hybridization of music and other art forms, making distinctions between interdisciplinary, multidisciplinary, and cross-disciplinary practices.[46] In his book Visible Deeds of Music, he examines how principles of modernist thinking from the late nineteenth- and early twentieth centuries enforced the concept of media purity, or the search for the “essential” characteristics of a given art form. Through this lens, music is seen as being distinctly separate from painting, and painting from theater, etc.[47] In academia, this viewpoint is reflected in the curricula which separate conservatories of music from liberal arts colleges or schools of design. For those who have matriculated through these institutions, the essential divisions between artistic disciplines are often reinforced, giving us an altered perspective of what it means to be a practitioner of a given discipline. To counter this position, Shaw-Miller presents compelling evidence that for a majority of western history, divisions between the arts were far less strict than the essentialist boundaries enforced over the past 150 years. In actuality, the differences between music (temporal art) and the visual arts (spatial art) have been historically considered as a “a matter of degree, not of kind,” as it is aptly put by Shaw-Miller.[48] By taking the position that the arts exist on a continuum, we can create a freer pathway for embracing elements of different practices.

Exploring hybridity in the arts can help explain the relationships between two or more given art forms, allowing us to gain a sense of the priorities and functions of the materials at work. Shaw-Miller expounds upon the work of philosopher Jerrold Levinson (born 1948), who described the hybridity of art in terms of juxtaposition (reenvisioned as multidisciplinary), synthesis (interdisciplinary), and transformation (cross-disciplinary).[49] Multimedia installations such as the American pianist and composer David Tudor’s (1926‒1996) collaborative work Rainforest, premiered in 1968, can be referenced as an example of a multidisciplinary work, where sculpture, lighting, and sound are presented without an overarching narrative, and where the impression of whether the event was predominantly “visual art” or “music” is left to the individual’s personal experience. Interdisciplinary works are those which combine multiple art forms into something wholly new. Richard Wagner’s Gesamtkunstwerk is a classic example, especially with relation to song, poetry, and theater. More recent interdisciplinary projects appear in forms such as the light and sound installations of Robert Henke (born 1969)[50] in locations like Berlin’s Kraftwerk arts space. These works involve massive laser-light fixtures, moving sculptural components, and diffused ambisonic sound, blending together into one gigantic event while making any “primary” element virtually impossible to single out as the driving force behind its existence. Finally, cross-disciplinary works create an imbalance in the relationship between the involved art forms. Originally described by Levinson as transformative art, the imbalance of cross-disciplinary practices can also be seen as an augmentation of sorts.[51] One artistic discipline lends its abilities to another, thereby transforming it and amplifying its expressive capabilities. Music videos are indicative of cross-disciplinary works in many ways. First the music is produced, which then bonds with an unfolding visual narrative meant to elevate its emotional as well as structural characteristics. Yet, each medium tends to adopt either a primary or secondary role. Perhaps one can glean a feel of the uneven relationship between the two mediums with a little word play; are they music videos, or video music?

Graphic notations can also be included in the world of cross-disciplinary practices, where notation acts as the primary identifier, and graphics as the second. These lines typically hold in most cases but can, of course, be challenged. British composer Cornelius Cardew’s (1936‒1981) experimental score for his work Treatise (1967) treads that line carefully by existing as (highly subjective) musical instruction, but also as a captivating visual theme and variations on traditional notation’s graphic syntax. Other works, such as American composer Aaron Cassidy’s (born 1976) topographically oriented 2nd String Quartet (2010), engage with precise graphic vectors mapped across the body of a string instrument. The real challenge for composers lies in how they navigate this cross-disciplinary space. It seems clear (as evidenced by Score Follower) that within the current technological ecosystem—one saturated with the ubiquitous presence of graphical user interfaces—that visual display techniques can provide the composer with an extensive pool of enticing opportunities for novel notations and thus musical interactions. The pull towards new representations of music notation has even spurred the creation of conferences intended to unite engineers, designers, and composers alike to address what “notation” means in the twenty-first century (such as the TENOR conference which began in 2015). In the past, sharp criticisms of graphic notation emanating from voices such as Pierre Boulez have perhaps contributed to feelings of apprehension when attempting to employ graphics in a given notation, either partially or exclusively. In Orientations, a collection of Boulez’s writings on music composition (originally stemming from lectures given at Darmstadt in 1960), he makes a series of firm judgments on purely “graphic notations.”[52] He considered such systems (i. e., non-grid based structures, or other novel graphical mappings) as appealing to less complex mental processes which serve as a “regression”[53] of musical development. In essence, Boulez considered graphical constructs as existing outside an indexical information space provided by the grid of western notation, thereby avoiding higher-level structural organization and interpretation. What Boulez inadvertently dismisses (among other underlying cultural issues within his positions), is that any particular graphic channel of information (e. g., hue, width, curvature) is an opportunity for layering complex information more precisely, not less so. Balancing the importance of structural clarity and visual complexity is a central focus of information design theory.

Western notation primarily supports a particular quantized pitch-duration structure within a fixed instrumental timbre space. It is just one of many possible graphical-musical symbiotic relationships. An implied meaning gleaned from Boulez’s writing on notation could be that these “graphic” components are more difficult to assimilate into traditional notation structures, and thus, such techniques should be avoided. This is due to the absence of consideration for how carefully designed graphics can increase information bandwidth while maintaining one’s desired degree of information resolution. Doing so requires a nuanced understanding of the visual interplay between objects and a steady hand when adding new variables to the equation of perceptual clarity. While Boulez avoids rejecting the potential of such use cases, the absence of discussion around it is problematic. Lumping graphic notations into one broad (“regressive”) category suggests how these lines of thinking can work counter to developing meaningful relationships within a new notation system. A successful union of graphic elements and musical meaning requires an acknowledgement of the complexity of visual stimuli, and of how the realm of perception can play a crucial role in balancing these elements.

Cross-modal Interpretations

The compositions of American composer, improviser, and multi-instrumentalist Anthony Braxton (born 1945) occupy a unique space within the domain of graphic scores by providing an intrinsic link between visual perceptual phenomena and the notation’s design. Throughout his career, Braxton has often described his music as being “trans-idiomatic,”[54] or in other words, music which navigates relationships to, but not exclusively definable by, European and African traditions. By refusing to label himself as belonging to one tradition or another, Braxton sets his sights on creating an architecture for musical interaction—a space for musicians to enter, navigate, and explore. Journalist and lecturer Graham Lock summarizes Braxton’s approach by proposing that he is guided by the concept of the “synesthetic ideal,” a theory of the aesthetic and spiritual relationship between visual and musical constructs found in Braxton’s compositions.[55] This includes the use of graphic notations as representations of the mental imagery and possible synesthesia experienced by Braxton as a means of evoking spiritual connections between the performer and the score. In maintaining an openness towards the integration of more complex graphic elements, balanced by tradition and subjective experience, Braxton’s systems of notation carefully navigate how relationships manifest between the score and performer. The notion of the synesthetic ideal sheds light on several important characteristics central to Braxton’s conception of the role of musical notation, specifically relating to the dimensionality of its representational affordances. Here, western notation is referred to by Braxton as being “two-dimensional”[56] in terms of its pitch/time axis, which aligns closely with Trevor Wishart’s critique of the western “lattice”[57] structure (Figure 5) and the limitations it faces in adequately representing the complex timbral interactions (coined by Wishart as a “complex sound object”[58]) which often comprise the compositional grammar of electronic music.

Figure 5: An illustration of Trevor Wishart’s “lattice” structure[59]

In Anthony Braxton’s view, the communicative bandwidth of spoken and written language itself could arguably be found to be even more limited than music notation, where he often describes it as being “mono-dimensional.”[60] This goes along with his tendency to avoid naming his compositions verbally, opting for visual titles or diagrams which convey the spiritual and multi-perceptual dimensions of his work.[61] In Lock’s interviews with Braxton, the painter Wassily Kandinsky is often noted as an important influence on his compositional style and as another artist with synesthetic influences. Kandinsky’s conviction that music could serve as a spiritual conduit to new forms of art resonates with Braxton, serving as an affirmation of the deep and even sacred relationship between sound, vision, and the beauty of collaborative human creativity. At Weimar Bauhaus, Kandinsky developed a style working with distinct visual channels,[62] a key similarity to current information design practice where perceptual bandwidth is a guiding principle. While Braxton does not specifically reference any particular visual constructs found in Kandinsky’s work, he does seem to intuit (perhaps as a fellow synesthete) how visual perception can allow for specific musical-graphical associations.

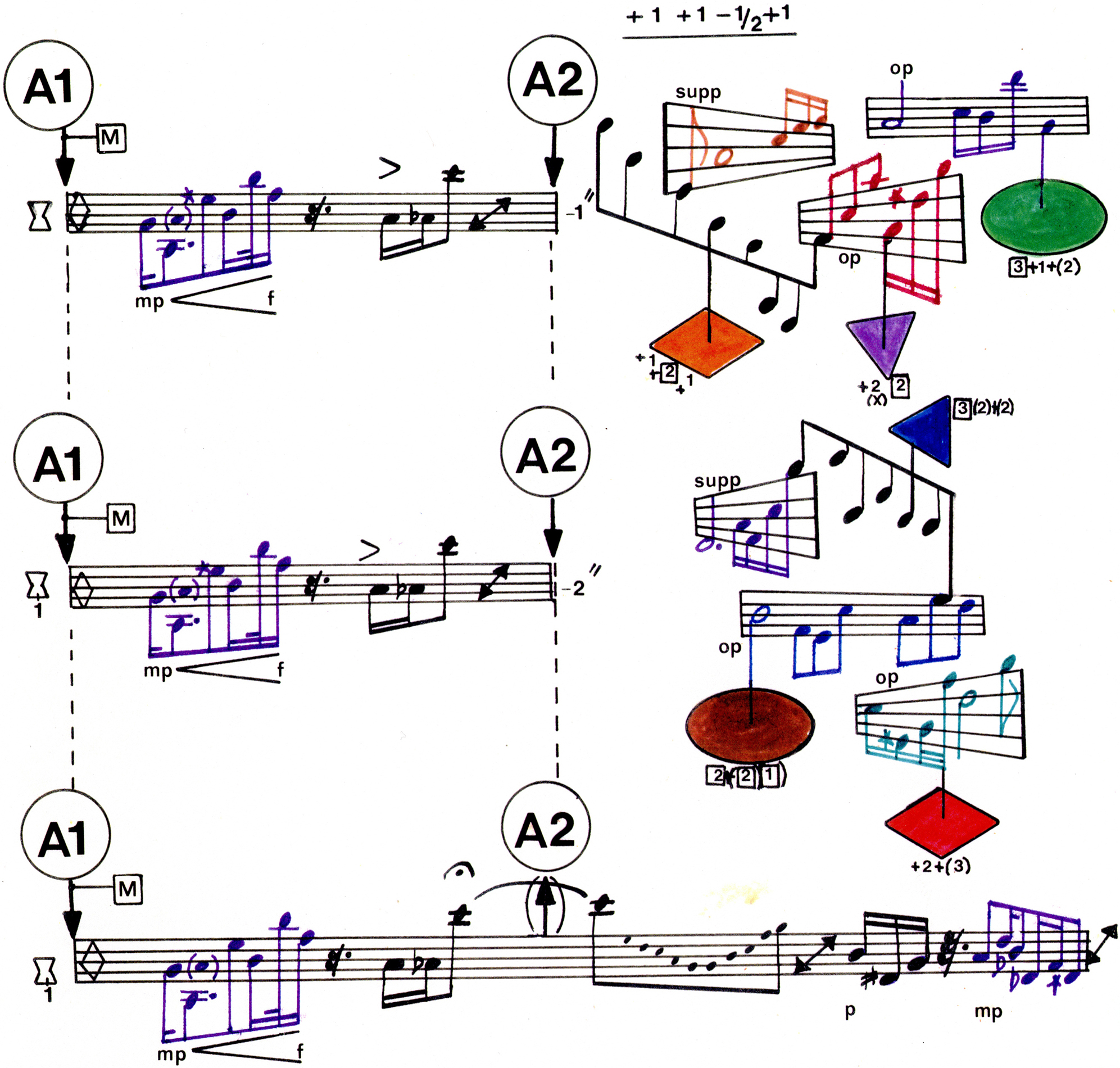

Figure 6: Anthony Braxton, Composition 76 (1977)[63]

When described in terms of information design, Braxton’s Composition No. 76 (1977) (Figure 6) maps luminosity and hue (i. e., shade and color) to an emotive musical phrasing scheme; green, red, and other hues are mapped to interpretations of low or high sentimental intensity, where the lightness or darkness (luminosity) of those hues indicates changes of dynamics or tempo.[64] Braxton’s unique understanding of the role that perception plays in cultivating expressive interactions between notation and performer is in many ways prescient, as current multisensory research has shown that not all relationships between sight and sound are as arbitrary as once thought.[65] This is evident within the field of multisensory perception, as it pertains to cross-modal interactions in the brain. Such activity allows the mind to synthesize information into a perceptual whole and facilitate abstract processes such as language and metaphor, but also to allow for phenomena such as synesthesia.[66] The “Bouba-Kiki effect,” where visual shapes are linked with specific sounds, illustrates these intrinsic connections in relation to visual and aural perception.[67] In synesthetes, such interactions can trigger “cross-domain resonance,” where one sense evokes another, highlighting the natural integration of multi-sensory aspects within the brain.[68] Understanding these processes offers valuable insights into visual-aural communication, specifically in relation towards new notational systems. This in turn carries with it significant lessons for the creative use of technology in the wider field of HCI, but also written music and the role of notation.

Making Meaning

When composers engage with traditional western notation methods in their compositions, they benefit from an audience with widespread familiarity and musical literacy. Western-derived compositional techniques still enjoy a form of cultural hegemony by offering specific support for many core and quantifiable parameters, ranging from micro features such as note values and tunings, to macro features such as instrumental arrangement. As described by composer and musicologist Mieko Kanno, western notation’s standardization allows it to operate “descriptively,” in that the symbols on the page essentially inform the player and the reader of what they should hear.[69] When notating a composition using this system, it is assumed that there are enough performers capable of interpreting a composer’s idea in a manner that both parties find worthwhile. These advantages, especially the descriptive properties of traditional western notation, offer a degree of predictability to its users, whereas any experimental notation bridging (especially those new technologies) can feel unmoored from common expectations. This sentiment runs the risk of generating less incentive for engaging with larger perceptual questions of creative interaction which are embraced within the fields of HCI and information design. However, as evidenced by the works found on Score Follower, there is a growing current of creative energy surrounding not only the interactive and expressive capabilities afforded by electronic and digital instruments, but also the new methodologies available for representing and structuring musical ideas.

The notion of uncertainty in contemporary music notation practices, while often framed as a consequence of technological innovation, can also be understood as a feature intrinsic to the history and function of notation itself. Traditional western notation, while containing prescriptive properties, also benefits from its interpretive flexibility. Performers regularly navigate the space between what is notated and what the score inspires, negotiating its many expressive features. This interpretive leeway is a core feature which is carefully calibrated by the composer to cultivate musical richness and engagement. In the context of HCI and contemporary notation practices, we might therefore distinguish between the uncertainty generated by interpretative openness, and the opportunities afforded by new representational formats. While the former has long been embedded in the performer’s role, the latter presents more structural challenges for both composers and readers of new scores. Interpretive uncertainty can also be reframed as interpretive freedom, something any score employing HCI display techniques will surely want to accommodate. The continued examination of how these two categories of change interact can provide creative practitioners with useful insights into how new systems of notation mediate their meaning and influence the performer’s agency. Integrating HCI practices offers a range of opportunities for addressing the timbral-representational challenges of the “complex sound object”[70] as articulated by Trevor Wishart.

A pathway forward may be found in a more recent “third wave” in HCI, one which extends beyond the efficiency-driven second wave previously discussed. Not all interactions with technology need to have a specific end goal, one which can be optimized for some kind of meaningful result for improving “performance.” Nor do all interactions have to be mitigated for possible “errors” or “unexpected” outcomes. Sometimes, people simply want to use technology for its creative and expressive affordances. This is precisely the realm of the “third wave” of HCI.[71] This framework[72] adopts the position that a user’s previous experiences, capabilities, and situational context matter just as much if not more than the mitigation of user mistakes.[73] In digital instrument design circles, research has been focused on not just the physical and ergonomic relationship a controller has with the performer, but also on the virtual mapping between the instrument and the synthesis of its sound.[74] Those mappings have the ability to change our physical relationship with the instrument, and thus play a large role in determining the success or failure of a given design. Success in this context is typically defined as one which promotes user creativity regardless of an individual’s skill level. New users can attain immediate results, while experts still find enough room to continuously expand their expressive capabilities through the instrument. It is here that user perception, physical abilities, and creative potential are all woven together in the design process of the instrument. To quote music interaction researcher Joseph Malloch, the third wave is where “ambiguity is celebrated, and enchantment or joy are seen as legitimate criteria of success.”[75]

By adopting third wave positions towards the analysis and creation of music notation, perhaps we can envision an exciting and innovative future for written music; one which becomes interlaced with traditional methods of composition and the expansive flexibility of new technology. The process of customizing a notation or designing one from scratch for a composition may stand to gain a great deal by being viewed in the same light as interaction design processes. Third wave principles of HCI ultimately seek to create effective spaces for making meaning, much in the same way as the scores of Anthony Braxton, but with the added potential for composers to home in on the resolution of performative information found within the score. By the same token, notations engaging with HCI principles and constructs may be contributing to an emergent form of standardization, guided by the perceptual boundaries of the human mind. Traditional western music notation is a monumental success in terms of information design, but it also came into being with very different musical possibilities and constraints than those which composers face today. With further studies exploring the perceptual impact of various visual-representational constructs for music notation, composers can exercise more nuanced control over the systems they create, while allowing for more sophisticated forms of analysis of the compositional process in music theory, especially in terms of action and gesture-based scoring. For composers considering a Score Follower submission, possibilities can extend from the established western tradition to graphic and interactive scores that make human perception a core element of their instructional design. Scores being created today may feel as though they occupy a space of one, especially when it comes to implementing new graphical-representational techniques. Soon, though, we may begin to see the emerging footprint of information design practices, shaped by HCI. By engaging with the mechanics of multisensory perception, information graphics, and musical interaction, powerful languages of musical expression can emerge. While navigating the digital episteme may feel challenging due to its reorienting effects, it offers us the rare opportunity to redefine the relationships we have between input-output, signified-signifier, and composer-performer.

Notes

Max (formerly Max/MSP) is a visual programming environment for music and multimedia developed by Cycling ’74. | |

Agostini/Ghisi 2012. | |

The Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems (CHI) is the flagship annual research conference hosted by the Association for Computing Machinery (ACM). | |

For more information on NIME, the International Conference on New Interfaces for Musical Expression, see: https://www.nime.org (11 Nov 2025) | |

The International Conference on Technologies for Music Notation and Representation (TENOR) is an annual meeting on state-of-the-art research and creative practices in notation and other music representational strategies. | |

Score Follower is a US-based nonprofit organization that curates and publishes synchronized score videos on YouTube; its scorefol.io platform is operated by Score Follower LLC. | |

See https://web.archive.org/web/20250806172550/https://www.scorefollower.org/ (11 Nov 2025) | |

https://web.archive.org/web/20240619210832/https://www.scorefollower.org/fms/ (3 Dec 2025) | |

https://www.youtube.com/channel/UCsCyncBPEzI6pb_pmALJ9Tw (11 Nov 2025) | |

See the call in Cambridge University Press of 2025: “New Strategies for Music Notation and Representation in Electroacoustic Music.” https://www.cambridge.org/core/journals/organised-sound/announcements/call-for-papers/call-new-strategies-for-music-notation-and-representation-in-electroacoustic-music (11 Nov 2025) | |

Mizruchi 2020. | |

MacKenzie 2024. | |

Institutions like the Institute for Research and Coordination in Acoustics/Music (IRCAM, Paris) and the Centre for Interdisciplinary Research in Music, Media, and Technology (CIRMMT, Montreal) are research-creation centers that join musical practice with science and engineering through the operation of studios, labs, and concert spaces. | |

Magnusson 2019. | |

Ibid., 6. | |

Ibid., 1‒14. | |

Houser 2010, 89–100. | |

Magnusson 2019, 184. | |

Malloch 2014. | |

Image courtesy of the IDMIL (Input Devices and Music Interaction Lab). For information on the “T-Stick” see: https://www.idmil.org/project/performing-a-piece-from-a-dmi-repertoire-case-study-with-the-t-stick/ (11 Nov 2025) | |

Magnusson 2019, 239–240. | |

Vasquez/Tahiroğlu/Kildal 2017. | |

Cadoz 2009, 217. | |

Giordano/Sinclair/Wanderley 2012. | |

Cadoz 2009, 226. | |

Miller 2017. | |

D’Errico 2016, 31. | |

Matthew Ingram cited after D’Errico 2016, 65. | |

Ableton Live is a digital audio workstation made by Ableton (Berlin), used for composition, production, and live performance. | |

DeSantis 2015. | |

Alfano 2023. | |

Hope 2017. | |

Ibid., 24. | |

Image courtesy of the composer. In addition to explaining the score for Speechless, Hope’s TENOR 2018 paper also outlines her development of the Decibel ScorePlayer, the tablet-based system that delivers the work’s synchronized animated notation; see Hope/Wyatt/Thorpe 2018. | |

Tufte 1990, 81‒96. For the quote from Klee, see ibid., 81. | |

Ibid., 81. | |

Goldstein 2010, 214. | |

Tufte 1983, 106. | |

Blackwell/Green 2003. | |

Ibid., 9. | |

Ibid. | |

Ibid., 17. | |

Adapted from ibid. Each notational element appears as an entity linked to others with the “1” and “M” markers indicating one-to-many relationships and the box colors grouping categories of symbols to clarify how these dependencies interact. For a guide to ERMIA notation, see Green/Benyon 1996. | |

Harrison/Tatar/Sengers 2007. | |

Tufte 1997. | |

Shaw-Miller 2002. | |

Ibid., 11. | |

Ibid., 4. | |

Levinson 1990, 26–36. | |

Henke is a German composer and sound artist, co-creator of Ableton Live; he releases as Monolake and is known for laser-based audiovisual works. | |

Levinson 1990, 30. | |

Boulez 1986. | |

Ibid., 84. | |

Braxton 2004. | |

Lock 2008, 6. | |

Ibid., 4. | |

Wishart 1996, 11. | |

Ibid., 26. | |

The figure demonstrates the quantized 2D space of pitch and duration, where complex timbre forms—beyond the capabilities of a single acoustic instrument—are notated by layering multiple instruments. | |

Lock 2008, 7. | |

Radano 1993, 137‒138. | |

See, for example, Vassily Kandinsky’s Gelb-Rot-Blau (Jaune-rouge-bleu) from 1925. https://www.centrepompidou.fr/en/ressources/oeuvre/cEpEKE (11 Nov 2025) | |

Score excerpt courtesy of Anthony Braxton and the Tri-Centric Foundation. Braxton’s notation employs color fields, shapes, and spatial groupings, illustrating how distinct visual channels can act as performance parameters in real time and support his trans-idiomatic practice. | |

Steinbeck 2018. | |

Ramachandran/Marcus/Chunharas 2020. | |

Purves 2004. | |

Ramachandran/Hubbard 2001 and Köhler 1929. | |

Ramachandran/Marcus/Chunharas 2020, 4. | |

Kanno 2007, 232. | |

Wishart 1996, 26. | |

Filimowicz/Tzankova 2018. | |

Beyond third-wave HCI, current discussions in HCI describe “Entanglement HCI,” which treats humans and technologies as inseparable sociomaterial systems and emphasizes relations, responsibility, ethics, and more-than-human perspectives; see Frauenberger 2020. | |

User mistakes can be thought of as everyday interaction errors: pressing the wrong control, being in the wrong mode, choosing the wrong item, or mistiming a step. | |

The term “virtual mapping” refers to the software layer that links controller inputs (sensors, keys, motion) to synthesis or processing parameters, specifying how gestures yield sound. See Hunt/Wanderley/Paradis 2003 and Wanderley/Depalle 2004. | |

Malloch 2014, 9. |

References

Agostini, Andrea / Daniele Ghisi. 2012. “Bach: An environment for computer-aided composition in max.” In International Computer Music Conference 2012 Ljubljana: 373–378. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/298980928_BACH_AN_ENVIRONMENT_FOR_COMPUTER-AIDED_COMPOSITION_IN_MAX (11 Nov 2025)

Alfano, Mark. 2023. “Hermeneutic Calvinball versus Modest Digital Humanities in Philosophical Interpretation.” Humanities and Social Sciences Communications 10/1: 1–9. https://doi.org/10.1057/s41599-023-02164-1

Blackwell, Alan / Thomas Green. 2003. “Notational Systems – The Cognitive Dimensions of Notations Framework.” In HCI Models, Theories, and Frameworks: Toward an Interdisciplinary Science, edited by John M. Carroll. San Francisco: Morgan Kaufmann, 103–134.

Boulez, Pierre. 1986. “Time, Notation and Coding.” In Orientations: Collected Writings. London: Faber and Faber, 84–89. First published 1985 as “Zeit, Notation und Kode” in Musikdenken heute II. Mainz: Schott, 63–69.

Braxton, Anthony. 2024. “My Conversation with Anthony Braxton.” [2001] All About Jazz. August 16, 2024. https://www.allaboutjazz.com/my-conversation-with-anthony-braxton (11 Nov 2025)

Cadoz, Claude. 2009. “Supra-Instrumental Interactions and Gestures.” Journal of New Music Research 38/3: 215–230. https://doi.org/10.1080/09298210903137641

D’Errico, Michael Anthony. 2016. Interface Aesthetics: Sound, Software, and the Ecology of Digital Audio Production. PhD thesis, University of California, Los Angeles. https://escholarship.org/uc/item/0mv9v64c (11 Nov 2025)

DeSantis, Dennis. 2015. Making Music: 74 Creative Strategies for Electronic Music Producers. Berlin: Ableton AG.

Filimowicz, Michael / Veronika Tzankova, eds. 2018. “Introduction: New Directions in Third Wave HCI.” In New Directions in Third Wave Human-Computer Interaction: Volume 1 – Technologies. Cham: Springer, 1–10.

Frauenberger, Christopher. 2020. “Entanglement HCI: The Next Wave?” ACM Transactions on Computer-Human Interaction 27/1: 1–27.

Giordano, Marcello / Stephen Sinclair / Marcelo M. Wanderley. 2012. “Bowing a Vibration-Enhanced Force Feedback Device.” In Proceedings of the 12th International Conference on New Interfaces for Musical Expression. https://www.nime.org/proceedings/2012/nime2012_37.pdf (11 Nov 2025)

Goldstein, E. Bruce. 2010. Sensation and Perception. Belmont: Wadsworth.

Green, Thomas R. G. / David R. Benyon. 1996. “The skull beneath the skin: entity-relationship models of information artifacts.” International Journal of Human-Computer Studies 44/6: 801–828.

Harrison, Steve / Deborah Tatar / Phoebe Sengers. 2007. “The Three Paradigms of HCI.” In Alt. Chi. Session at the SIGCHI Conference on Human Factors in Computing Systems, San Jose, California, USA. https://people.cs.vt.edu/srh/Downloads/TheThreeParadigmsofHCI.pdf (11 Nov 2025)

Hope, Catherine Anne “Cat.” 2017. “Electronic Scores for Music: The Possibilities of Animated Notation.” Computer Music Journal 41/3: 21–35. https://doi.org/10.1162/comj_a_00427

Hope, Cat / Aaron Wyatt / Dan Thorpe. 2018. “Scoring an Animated Notation Opera. The Decibel ScorePlayer and the Role of the Digital Copyist in Speechless.” In Proceedings of the International Conference on Technologies for Music Notation and Representation (Tenor 2018), edited by Sandeep Bhagwati and Jean Bresson. Montréal: Concordia University, 193–200. https://www.tenor-conference.org/proceedings/2018/25_Hope_tenor18.pdf (3 Dec 2025)

Houser, Nathan. 2010. “Peirce, Phenomenology and Semiotics.” In The Routledge Companion to Semiotics, edited by Paul Cobley. London: Routledge, 89–100.

Hunt, Andy / Marcelo M. Wanderley / Matthew Paradis. 2003. “The Importance of Parameter Mapping in Electronic Instrument Design.” Journal of New Music Research 32/4: 429–440.

Kanno, Mieko. 2007. “Prescriptive Notation: Limits and Challenges.” Contemporary Music Review 26/2: 231–254. https://doi.org/10.1080/07494460701250890

Köhler, Wolfgang. 1929. Gestalt Psychology: An Introduction to New Concepts in Modern Psychology. New York: Liveright.

Levinson, Jerrold. 1990. Music, Art, and Metaphysics: Essays in Philosophical Aesthetics. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press.

Lock, Graham. 2008. “‘What I Call a Sound’: Anthony Braxton’s Synaesthetic Ideal and Notations for Improvisers.” Critical Studies in Improvisation 4/1: 1–23.

MacKenzie, I. Scott. 2024. Human-Computer Interaction: An Empirical Research Perspective. Cambridge, MA: Morgan Kaufmann (Elsevier).

Magnusson, Thor. 2019. Sonic Writing: Technologies of Material, Symbolic, and Signal Inscriptions. London: Bloomsbury Academic.

Malloch, Joseph. 2014. A Framework and Tools for Mapping of Digital Musical Instruments. PhD thesis, McGill University. https://escholarship.mcgill.ca/concern/theses/ht24wn370 (11 Nov 2025)

Miller, Daniel. 2017. “Are Scores Maps? A Cartographic Response to Goodman.” In Proceedings of the International Conference on Technologies for Music Notation and Representation (Tenor 2017), edited by Helena López Palma, Mike Solomon, Emiliana Tucci, and Carmen Lage. A Coruña: Universidade da Coruña, 57–67. http://tenor-conference.org/proceedings/2017/07_Miller_tenor2017.pdf (11 Nov 2025)

Mizruchi, Susan L., ed. 2020. “Introduction: Libraries and Archives in the Digital Age.” In Libraries and Archives in the Digital Age, Cham: Palgrave Macmillan, 1–9.

Purves, Dale. 2004. “The Association Cortices.” In Neuroscience, edited by Dale Purves, George J. Augustine, David Fitzpatrick, William C. Hall, Anthony-Samuel Lamantia, James O. McNamara and S. Mark Williams. Sunderland: Sinauer Associates, 613–636.

Radano, Ronald M. 1993. New Musical Figurations: Anthony Braxton’s Cultural Critique. Chicago: University of Chicago Press

Ramachandran, Vilayanur S. / Edward M. Hubbard. 2001. “Synaesthesia – A Window into Perception, Thought and Language.” Journal of Consciousness Studies 8/12: 3–34.

Ramachandran, Vilayanur S. / Zeve Marcus / Chaipat Chunharas. 2020. “Bouba-Kiki: Cross-Domain Resonance and the Origins of Synesthesia, Metaphor, and Words in the Human Mind.” In Multisensory Perception: From Laboratory to Clinic, edited by K. Sathian and V. S. Ramachandran. London: Academic Press, 3–40.

Shaw-Miller, Simon. 2002. “Ut Pictura Musica: Interdisciplinarity, Art, and Music.” In Visible Deeds of Music: Art and Music from Wagner to Cage. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1–35.

Steinbeck, Paul. 2018. “Improvisation and Collaboration in Anthony Braxton’s Composition 76.” Journal of Music Theory 62/2: 249–278. https://doi.org/10.1215/00222909-7127682

Tufte, Edward R. 1983. The Visual Display of Quantitative Information. Cheshire, CT: Graphics Press.

Tufte, Edward R. 1990. Envisioning Information. Cheshire, CT: Graphics Press.

Tufte, Edward R. 1997. Visual Explanations: Images and Quantities, Evidence and Narrative. Cheshire, CT: Graphics Press.

Vasquez, Juan Carlos / Koray Tahiroğlu / Johan Kildal. 2017. “Idiomatic Composition Practices for New Musical Instruments: Context, Background and Current Applications.” In Proceedings of the International Conference on New Interfaces for Musical Expression (NIME 2017), Aalborg University Copenhagen, 174–179. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.1181424

Wanderley, Marcelo M. / Philippe Depalle. 2004. “Gestural Control of Sound Synthesis.” Proceedings of the IEEE 92/4: 632–644. https://doi.org/10.1109/JPROC.2004.825882

Wishart, Trevor. 1996. On Sonic Art. Edited by Simon Emmerson. New York: Routledge.

Technische Universität Berlin

Dieser Text erscheint im Open Access und ist lizenziert unter einer Creative Commons Namensnennung 4.0 International Lizenz.

This is an open access article licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License.