“Punk rock can never be new again”

On the Horizons of Punk Music Scholarship

Bernhard Steinbrecher

Dieser Artikel zielt darauf ab, eine musiktheoretische Perspektive auf Punk zu entwickeln, die eng mit genretypischen Diskursen und Praktiken verknüpft ist. Musikwissenschaftlicher Ausgangspunkt ist die elementare Frage danach, wie sich analytische Beziehungen zwischen dem Klanggeschehen und den Arten und Weisen, wie es gemacht, gehört, erfahren und mit Bedeutung versehen wird, herstellen lassen. Am Beispiel von Punk wird reflektiert, inwieweit musikorientierte Interpretationen dabei helfen können, die Konstituierung und wiederholte Aushandlung von popularmusikalischen Genres besser zu verstehen. Dabei wird ein analytischer Bezugsrahmen entworfen, dessen Ankerpunkte – so die These – das Spektrum an Möglichkeiten eingrenzen, warum Punk so klingt, wie er klingt. Um die Rolle der Musik in diesen Zusammenhängen genauer zu beleuchten, werden die drei Analyseschwerpunkte Textur, Struktur und Spannungsgehalt vorgeschlagen.

This article develops a music-oriented punk theory in relation to genre-specific discourses and practices. In a step-by-step-manner, it reflects – with the example of punk – upon the fundamental question of what music analysis and interpretation can contribute to the understanding of how a popular music genre is negotiated and (re-)created, aiming to offer a new perspective on the analytical connection between the sounds and the ways in which they are made, listened to, experienced, and made sense of. The article proposes an analytical framework including different anchor points that hold together what punk tends to be like, examines the interrelations that delimit the range of possibilities for why punk sounds the way it does, and suggests three different and interwoven music-analytical focal points – texture, structure, and tensity – to illuminate the role of the music within this framework.

For almost five decades, the term “punk” has been a steady particular of popular music. With its preliminaries in the garage and avant-garde rock of the late 1960s and its broad public breakthrough with the Sex Pistols in 1976, punk, whether as an idea, genre, or aesthetic, has recurrently appeared both in countercultural realms and the mainstream frames of cultural debate. In academic discourse, punk left its marks early on as an important object of study, particularly in the cultural studies’ analytical endeavours, and has, as such, been an essential building block for the establishment of popular music studies. However, while its social, cultural, and political intricacies and visual and textual meanings have been strongly illuminated in scholarly discourse, there is relatively little analysis and contextual interpretation of punk’s actual sounds and musical makeup.[1] One reason for this neglect might be found in the – albeit ever weakening – musicological viewpoint that because of its (specific kind of) simplicity, a music is not worth closer musical examination (of any kind) – a fate that punk has come to share with chart-topping pop music. Nevertheless, perhaps an even more decisive claim explaining the lack of music-theoretical discussion is the general notion that punk is not necessarily a musical, or not even a music-related, phenomenon or field, but is rather, first and foremost, a specific attitude, stance, or lifestyle:

Punk isn’t punk because of the arrangement of chords, the speed of the songs, or a layer of crust in appearance, but in the way it breaks through the layers of social stagnation in everyday life and builds something else in its cracks.[2]

This musical foundation of punk – which I consider to be fundamental for grasping punk’s meaning – is avoided or undervalued by most writers, who tend to define punk instead primarily or even exclusively as an ‘attitude,’ a subcultural phenomenon, a youth movement or a political intervention.[3]

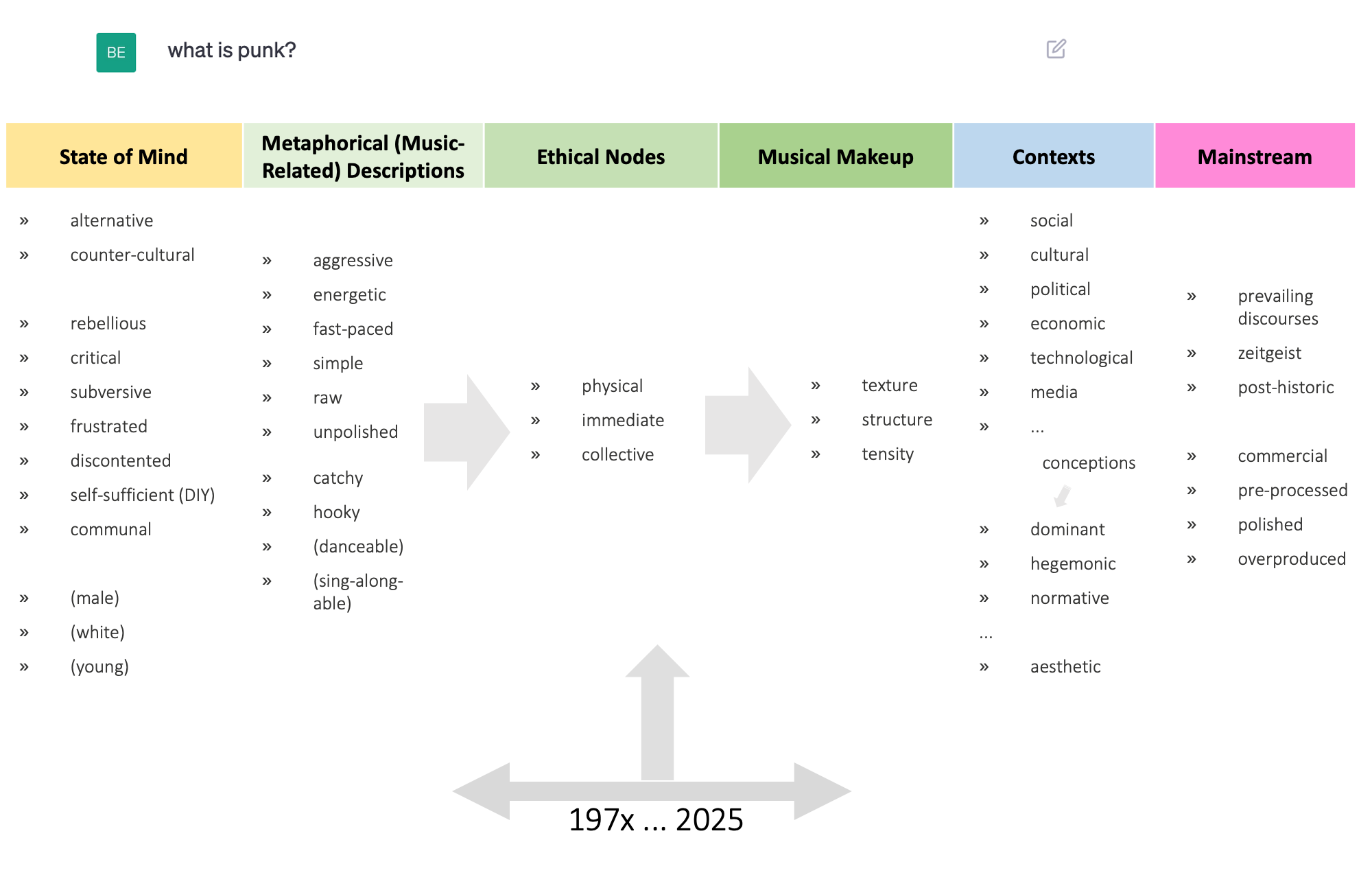

In this article, I approach the music of punk in a rather inverted manner, first by taking precisely the latter perspective as a starting point to theorize the genre’s sonic constellations and elaborate on the horizons of a music-oriented punk scholarship.[4] In doing so, my aim is not to comprehensively or exhaustively detail how punk sounds, but to elaborate on the interrelations that delimit the range of possibilities for why punk sounds the way it does. In a step-by-step manner, I will develop a theory of music’s place in the punk discourses and practices, reflecting – with the example of punk – upon the basal question of what music analysis and interpretation can contribute to the understanding of how a genre, understood as a discursive musical framework,[5] is negotiated and (re-)created. By taking this approach, I aim to offer a new perspective on a fundamental task of musicology concerning the establishment of a connection between the (analysis of the) sounds and (their interpretation in connection with) the ways in which they are made, listened to, experienced, and made sense of. The chart in Figure 1 shows a framework of the different analytical layers that I will leverage in my argument.

Figure 1: A punk framework

Punk as a State of Mind

To begin my reflections, I will begin very rudimentarily with the question of what punk actually is. Admittedly, at first glance, the question seems rather basic and unfruitful, and one might be inclined to leave definitional questions to “the consensus of users in the 1976–8 period, a consensus made up of the authors listed above together with musicians, journalists and other participants in published discourse.”[6] At second glance, however, it becomes clear that in hardly any other area of popular music, this overarching (and clearly exhausted) question is as powerful and inherently constitutive. This is particularly evident when it comes to the suspect notion that someone or something is not (any longer) punk. As the seminal German punk(-related) band Die Ärzte proclaim in their song “Ist das noch Punkrock?” (“Is that still punk rock?”):

But is that still punk rock

How your heart beats when she kisses you?

Is that still punk rock

When your favourite song is on the charts?

It’s just got the coolness factor

Of a garden tractor

Is that still punk rock?

I don’t think so[7]

The punk band Joseph Boys, on the other hand, finds that the term is, at least today, surrounded by some measure of arbitrariness: “Isn’t it outdated in 2022 to ask what punk is and what it is not? Can’t a gold foil be punk too?”[8]

To obtain a supposedly more unified notion of the punk idea, I consulted the “conversational AI model” ChatGPT to see which words and language patterns are most likely to occur in those contexts in which the term is used.[9] On 25 May 2023, I asked the free-of-charge version of ChatGPT the question, “what is punk?,” and in the first three paragraphs of the answer, the machine-learning algorithm provided me with the following information:

Punk is a subculture and music genre that emerged in the 1970s. It originated primarily in the United States and the United Kingdom as a rebellious response to the prevailing social and musical norms of the time. Punk is characterised by its aggressive and energetic music, often featuring short, fast-paced songs with simple progressions, raw and unpolished production, and confrontational lyrics that express frustration, discontent, and social criticism.[10]

In a renewed request on September 23, 2024, ChatGPT replied in a similar but more list-like way, adding at the very end of its answer that “Punk isn’t just about the music or fashion – it’s an attitude of defiance, self-expression, and resistance to the mainstream.”[11] This addition echoes the abovementioned core trope of punk, in that it is not just, if at all, about the sounds but “more than just music”: a way of life, a way of thinking, a mindset, an attitude, an ideology, a set of beliefs, or, as Laura Way discusses in her study of older punk women, it is conceived as a “state of mind.”[12] There are some common traits or “core values”[13] around which the state-of-mind nature of punk has been shaped, although all of them remain disputable in one way or the other.[14] Most importantly, it is closely tied to the idea that those who participate in punk are adopting a countercultural or, at least, alternative stance against prevailing norms and concepts.[15] This stance is expressed in a particular way – namely, through an openly critical, rebellious, and subversive attitude, often undergirded by frustration and discontent (rather than, for example, by peacefulness or hopeful thinking). Moreover, within this state of mind, independence and self-sufficiency are seen as central and are reflected in the do-it-yourself (DIY) narrative of punk;[16] or, as George MacKay puts it in his interrogation of this narrative, in the “DIY/punk nexus.”[17] And while the notion of individual freedom is an essential pillar of the punk trope, the shared values remain particularly powerful because of punk’s strong sense of community and the collective practices associated with it.[18]

Punk as a State of Mind in Context

Over the past five decades, punk’s core values have remained extraordinarily persistent, especially in comparison to many other popular music currents that have come and gone. As the Bad Religion singer and songwriter Greg Graffin put it at the end of his memoir, “What remarkable resilience, this punk thing!”[19] However, the circumstances or contexts in which these values have come alive and been charged with sense and meaning, time and time again, have certainly not remained in bloom. Since the first sparks of punk were lit, the social, cultural, political, economic, technological, media, and other contexts of which one might be critical and dismissive, or which may have tended to make one subversive and self-sufficient, have been subject to constant change. The same is true of the dominant conceptions and conventions within society that a punk might oppose in their rebellion against hegemonic power structures or certain ideas of what is or should be considered “normal.” This processuality entails that the abovementioned punk attitudes require constant adaptation and reshaping around their stable core.

For example, the reasons why a 16-year-old white male teenage punk in England might have been frustrated or rebellious in the late 1970s are likely to be very different from those of a 40-year-old female Black adult punk in South Korea in 2025. Nevertheless, both may share the same state of mind. Therefore, it becomes clear that there is a relationality to be considered. Laura Way argues in a similar vein when she notes the following, in relation to Mustafa Emirbayr:

Examining punk women’s past biographies as well as the present provided a deeper understanding of the relational nature of the attitudes and behaviours currently held/displayed and how (being) punk can be better understood as an unfolding, continual process (Emirbayer 1997).[20]

Following this, I would like to suggest a first grain of thought regarding the potential epistemic value of a more strongly pronounced music-oriented punk scholarship. It could be based on the following idea:

Studying punk helps us better understand the discursive and processual relationship between a community’s ingrained attitudes and a society’s dominant conceptions.

Within this perspective, there is much to be said for considering punk as a genre category, which would mean that it would refer to “a particular kind of music within a distinctive cultural web of production, circulation, and signification,”[21] in which “individuals and groups construct cultural boundaries.”[22] It could be considered as being defined through a socially accepted set of differently weighted and interdependent rules,[23] among them, formal and technical ones. What should strongly be considered in genre studies, however, is that genres are not monolithic historical phenomena that, once classified, remain immutable and self-actingly just there.[24] In their sociological reflections on genre work, Raphaël Nowak and Andrew Whelan note that,

Genre categorises and captures what we do and what we like. Genre is not, however, simply a disembodied referential point. Genre is cumbersome in verb form: ‘genre-ing’ describes the processes we are directing attention to as ‘genre work.’[25]

The fact is that punk, in particular, is a genre that is constantly in motion, or constantly being worked through. In Nowak and Whelan’s words, punk comprises “the practices which constitute both the music and the communities around it,”[26] and this becomes especially apparent when punk is viewed through the lens of the “developmental sequences” proposed by Lena and Peterson in their study of the types and trajectories of popular music genres. Punk is one of the few genres in their study (11 out of 60) to have gone through both the avant-garde, scene-based, industry-based, and traditionalist phases[27] – from its antecedents in the sixties, with its experimental, small-circle, and under-the-radar notions; through the late seventies/early eighties, when local and trans-local communities were quickly established, along with particular codes and demarcation mechanisms; to the early/mid-nineties, with what can be considered punk’s most commercially lucrative phase; and to the early noughties, when heritage preservation, nostalgia, and hyper-codification began to prevail. Not only has punk gone through this entire linear process, but it has also taken a more circular course, meaning that, although the traditionalist phase was reached two decades ago, earlier genre types continue to pop up here and there, across the globe, and initiate the trajectory over and over again in parallel (actually, the historiographies of punk are riddled with “generations” and “waves”).

With this circular perspective in mind, I would like to turn to the postmodern quote from the title of my article, which comes from a 2002 show preview for the band The Distillers: “Punk rock can never be new again.”[28] According to Lena and Peterson’s framework, punk can never be new again, because it has already completed the full course of a genre’s trajectory. However, this does not mean that the development is now frozen, and the genre is carved in stone. Rather, punk is constantly being reworked or repainted from a different starting point and context.[29] In this sense, I argue the following:

Studying punk helps us better understand the discursive and circular-processual relationship between a community’s ingrained attitudes and a society’s dominant conceptions by analyzing how the relationship is (re-)negotiated, stabilized, and renewed.

How and on what basis could this relationship possibly be studied? By what means do the protagonists of the punk community act within the mechanisms of their cultural frame and manoeuvre between their own state of mind and the current state of affairs? I think one of the main ways to address this gap can be found in the aesthetic forms through which these protagonists express themselves, and music is certainly one of them, if not the most important one. Then, how is the music shaped according to the discursive elements that “‘stick’ with it”[30] and the practices of production and reception? What are “the discursive and musical structures that concatenate into genre ideals and produce symbols of inclusion and exclusion?”[31]

What Punk is Negotiated With – The Role of the Music

Although there is the common perception that the music is not the most important element within the punk framework, I argue that it still has a fundamental, distinctive tone, and that the sonic makeup does not stray arbitrarily in any one direction. The punk band Joseph Boys, for example, whom I quoted at the beginning of my article, have expressed a critical/ironic attitude towards a clear definition of punk, even though they obviously have a pretty good idea of what punk sounds like. In the same interview, they were asked the following:

Plastic Bomb: “How would you categorise yourself? Are there any role models that are important for you?”

Joseph Boys: “It’s hard for me to assess this, and, to be honest, I always tell people that they should listen to it, it’s guitar music, it’s punk, that’s just what it is.”[32]

After all, “songs within a genre must share certain stable musical characteristics in order for the genre to be recognizable to consumers […].”[33] From a scholarly perspective, as indicated at my article’s beginning, only a few approaches have attempted to grasp punk from a musical point of view. As David Pearson puts it:

Scholars often assume that there is little more to say about punk music other than it is fast, loud, abrasive, and any amateur can perform it. Yet within the community of bands, fans, zine writers, concert organizers, and others constituting the punk scene, there is a robust discourse on punk musical style and the changes it has undergone throughout its now forty-year history. […] scholarship on punk has focused almost exclusively on its politics and culture without attempting substantive analysis of its music.[34]

To my knowledge, only a handful of English, German, or French monographs have an explicitly musical focus. These include Dirk Budde’s multi-dimensional music-analytical checklists of sixteen seminal punk and hardcore songs from the United States and the United Kingdom;[35] David B. Easley’s analysis of “style and sound” in early American hardcore punk;[36] my own work, where I use the post-hardcore band Fugazi as an example to which I apply my extended framework of popular music analysis;[37] Evan Rapport’s examination of musicality and race in early American punk;[38] and Sangheon Lee’s dissertation, which aimed to clarify “the music itself” of American hardcore punk and to decipher, through a musical lens, the “social dimension” of the music.[39] There have also been a number of articles on the musical aesthetics of punk, specifically on the rhythms, riffs, and timbres of 1990’s extreme hardcore punk;[40] the riff schemes and form in early American hardcore;[41] punk’s harmonic, melodic, and vocal-performative relationships to the blues;[42] and, with a process-oriented focus on a particular song, the gestural and textural features of the Sex Pistols’ song “Sub Mission,”[43] as well as the changing shapes and functions of riffs in Sonic Youth’s “Total Trash.”[44] Dave Laing also devoted a few pages to “voices” and “music” in his seminal book One Chord Wonders.[45]

I will incorporate some of these authors’ findings into my reflections below. First, however, it should be noted that when beginning to theorize the music within the discursive framework of punk, it would be unproductive to jump straight to the “musical structures”[46] in the narrower sense (a brief overview of this kind is provided by Pearson[47]), with the intent of obtaining an overview of the formative harmonic, melodic, or rhythmic aspects. To better understand how a certain state of mind is musically negotiated, it seems necessary to first consider what aesthetic criteria are in the playing field (i.e., what aesthetic claims are being made in punk music). As Henry Rollins pointedly asserted in the introduction of Don Letts’s documentary Punk: Attitude: “And all of a sudden, ‘fuck this’ has a backbeat.”[48]

In other words, what is especially interesting about punk is not the fact that power chords, distortion, or “skank”[49] beats are used, but rather why these devices lend themselves to being used within this particular framework. Repeating a distorted power chord at a fast tempo does not make you rebellious or subversive per se, and drumming a hardcore punk skank beat, even long before it had its specific adherence to punk or metal music, may simply be due to boredom, as Charlie Watts demonstrated in 1968 during the recording sessions for “Sympathy for the Devil.”[50] Therefore, I would like to add an intermediate level of analysis that includes more general musical descriptions that may be more directly related to the aforementioned punk attitudes.

Punk Music Metaphors

I hope I am not going out on a limb in supporting AI’s notion that punk is, according to popular belief, aggressive, energetic, simple, fast-paced, raw, and unpolished music.[51] I would also add that punk is inherently catchy and hooky, as the music makes strong affordances to be danced to and sung along to (although not in a conventional manner). These attributions need to be examined more closely and differentiated. First, from the perspective of cognitive psychology, they can be seen as embodied metaphors borrowed from the non-musical domains of human experience.[52] More specifically, they refer to a person’s experiential knowledge and impressions stored in their episodic memory, rather than to the general knowledge, including factual information, of their semantic memory.[53] Thus, while academia has often framed punk as an art form or socio-political phenomenon from the perspective of an abstract-conceptual system of references, punk music is apparently also very well describable by harking back to relative categories of a specific, near-stimulus kind that can only be assessed in terms of more-or-less[54] – there is, as far as I am concerned, no graded scale of aggressiveness, energy, or rawness.[55] The fact that we are dealing with relative categories here is also evident when we consider how the notions of aggressive or energetic, or more generally “hard” and “heavy”[56] music have changed drastically over the last fifty years.

Second, these attributions only work properly in terms of signifying punk through their interrelationships. For example, aggressive music can also be rather sluggish and slow, whereas the Hi-NRG (“high energy”) disco genre has little to do with punk music. Third, they point to different dimensions of the dynamic process of punk “musicking.”[57] The adjectives “raw” and “unpolished” generally refer to the working methods of those who make the music, “simple” and “fast-paced” to how they process the structural building blocks of the music, “aggressive” and “energetic” to what is to be conveyed and (physically) experienced, and “catchy” and “hooky” to how the listener is (mentally) drawn in.

Ethical-Aesthetic Criteria: Physicality, Immediacy, and Collectivity

Essentially, this bundle of metaphors not only contains translations of one’s auditory impressions or the images we may conceive of the musicians creating and playing, but also indicates the ethical criteria or ideal conceptions of the right or “correct” way to make and experience punk.[58] In the following, I propose three central anchor points or ethical nodes that structurally connect the (musical-)aesthetic criteria: physicality, immediacy, and collectivity. Together, these criteria interdependently contribute to the ways in which punk music constitutes itself or, more precisely, is expected to constitute itself and sound.

Physicality

Starting with the physical component of punk, I sense a dominance of bodily forms of creating, listening to, referring to, acting upon, or experiencing punk music to the detriment of theoretical or abstract thinking.[59] One discursive context in which this becomes apparent is when punk musicians discuss their relationship to musical theory or literacy. As I have discussed in detail elsewhere,[60] the inability to read or understand music from a (Western-)theoretical perspective is an essential part of the cultural legitimisation of one’s own creative practices in certain musical fields or genres; indeed, DIY and no-theory ethics are particularly popular in the punk context. I have argued that physical gestures (made with one’s arms, hands, and fingers) and the idea of feeling an instrument, rather than consciously reflecting upon what one is doing when playing it, are essential aspects of making rock music and its alternative, more phenomenally (gesturally, tangibly, and texturally) tied version of music theory.[61] This is especially true of the “no-holds-barred style”[62] of punk, which is most commonly played on physically manipulable instruments (e.g., guitar, bass, and drums) with a lot of body movement and intuitive, episodically remembered gestures on the fretboard or drums. Vocal delivery is also often the result of strong physical effort in shouting or screaming. In the reception of the music, the physical factor of feeling the sounds, moving to them excessively, and seeing or imagining how they are or were made is also fundamental.

Immediacy

Along with this dominance of physicality go notions of immediacy or, as Sangheon Lee has discussed at length, urgency.[63] A core narrative theme here is that punk has to get straight to the point and right in your face, without much physical distance: “‘Punk’ meant an attitude towards musical performance which emphasised directness and repetition […] at the expense of technical virtuosity.”[64] Punk has to be immediately perceptible rather than allusively thinkable; it has to be quickly created rather than conceptualized slowly on the drawing board, and it has to be played instantly without years of training and without aspiring to master an instrument or one’s own singing voice. Evan Rapport points to the sociocultural importance of this aspect, given that “[s]uch immediacy opened doors to many who otherwise might not have joined bands, dismantling the notion that music was the property of a select group of trained musicians.”[65] Immediacy became even more pronounced with the intensification of the genre in the form of hardcore punk, which “was and is a music of direct communication unencumbered by any musical excess.”[66]

Collectivity

Of course, these notions of physicality and immediacy only come into their own when performed or experienced collectively, rather than at home listening alone with one’s headphones on, noodling around on a guitar, or, these days, sitting in front of a computer screen and moving tiny blocks around in a digital audio workstation. Punk musicians most often interact and respond directly to each other when making music and when playing together in a conspiratorial gang, such as a band. Punk concerts are, almost by definition, spaces for reducing distance and making physical contact with others, including musicians, through pogoing, stage diving, sweating, spitting, or whatever else breaks down the barriers of peoples’ intimate zones.[67] The notion of collectivity is directly related to the community-oriented attitude of punk as a state of mind, which was mentioned earlier.

Taken together, these three ethical notions can be said to form a social acceptance framework for punk,[68] defining the extent to which something can be considered punk or perhaps no longer so. If a punk band, at some point in its career, no longer conveys the sense of an immediate and unadulterated artistic expression, because, for example, the use of studio technology becomes too obvious, the production time has become too long, there are too many people from the outside involved, the stages have become too big, and so on, then the band is likely to fall out of this framework of acceptance. Therefore, if we assume that the arcs between the ethical nodes of physicality, immediacy, and collectivity determine the direction of how punk should ideally be made and experienced, this may already limit or pre-determine the ways in which it actually sounds.

The musical interweaving within this complex interplay is aptly illustrated in a scene from the Danny Boyle-directed TV series about Steve Jones of the Sex Pistols,[69] in which bassist Glen Matlock tries to convince Jones (collectivity), with the help of music-theoretical vocabulary (no immediacy), of the intricacies of his harmonic idea (“C suspended 2nd”). Jones, however, accuses Matlock of being a “pensioner” rather than young, as a punk should be, and hits a loud distorted power chord (“C!”) on the guitar (physicality).[70] There is indeed a palpable pressure that comes from such a fifth chord being played at high volume, and there is also a strong gestural intuitiveness in moving this chord up and down the fretboard, as there is no need to change the shape of the hand. There is also no need to worry about major- or minor-scale relationships, as there is no third, and the vocalist can therefore shift into singing along quite easily and quickly. Similarly physical and immediate is the comfortable feeling of being enveloped in a cocoon of sound when hitting the drums with full force (or more force than usual). Dave Grohl of Nirvana and the Foo Fighters has spoken of this notion when asked about what punk drumming means to him, saying that it is “all about energy,” and that now, as a singer, he misses “the head in the middle of all that noise.”[71]

As the links between the internal nodes of my punk framework become stronger, I would like to expand my theory by adding the following:

Studying punk helps us better understand the discursive and circular-processual relationship between a community’s ingrained attitudes, its aesthetic forms of expression, and a society’s dominant conceptions by analyzing how the relationship is (re-)negotiated, stabilized, and renewed with regards to ethical notions of physicality, immediacy, and collectivity.

On the basis of this theory fragment, I would now like to finally delve deeper into the question that I have just touched on regarding how these different interrelations are musically negotiated or, conversely, how they determine how the music is built up.

The Shape of Punk That Came: Texture, Structure, and Tensity

To locate the musical makeup within the “praxis formation”[72] of punk, with its specific modes of collective thought and discursive instruments that enable listeners and musicians to negotiate musical value and make sense of the sounds they hear or produce,[73] I suggest that a musical analysis of punk might focus in particular on the relationship between idiosyncratic shapings of texture, structure, and tensity. Having said that, I think it is important to emphasize once again that it is not my intention, nor is it possible, to find or define universal principles that apply to every piece of punk music. Rather, my aim in the following is to describe and contextualize the basic layout and tools that help codifying a piece of music as punk (i.e., to integrate it into the punk framework). In fact, even the poppiest of pop punk, the most post of post-punk, or the most extreme of extreme hardcore punk must have, at least, a tiptoe on some common ground and use some common methods.[74] In the absence of any audible traces, the other “genre rules,” in Franco Fabbri’s terms (for example, semiotic, behavioural, social, and economic),[75] would theoretically form such a powerful combination that the negotiators of the genre community (musicians, audiences, critics, organizers, etc.) still agree to problematize the respective artist’s musical-aesthetic expression as punk. Or, to take up my argument from further above, that they can nevertheless interlock the sounds, somehow, between the punk framework’s different nodes.[76]

The idea of differentiating the analytical perspective into these three interrelated dimensions stems, in part, from the music-analytical framework that I have developed.[77] Their particular order here can be explained by the following questions: How does the texture feel, and what does it “look” like (texture)? What composite elements are encapsulated within it (structure)? And what effect does all of this have (tensity)? Another important aspect within these relationships, which I will not discuss further, is, of course, the lyrics of punk songs. The lyrics convey the aforementioned tropes content-wise, for example, through their typically fairly direct, unencrypted, and slogan-like speech, their call for (physical) action, and the us-against-them narratives; this conveyance is supported by how they are interwoven musically in terms of the “‘orationality’ of speech-like singing,”[78] the “sonorous quality” of rhymes, and the density and positioning of syllables within the verbal space.[79]

Texture

I use the idea of texture in its broadest sense, as representing the (or an) overall sound impression of a song characterized by its intensity and density caused by the formation and development of different streams and layers.[80] This approach goes beyond traditional, melody-centred notions of homophony or heterophony, as it also considers the effects of spectral and spatial distribution, articulation, and dynamics.[81] In The Poetics Of Rock, Albin Zak refers to texture as an inclusive quality of “composite sound images”[82] and classifies it as one of the five interdependent categories “that represent all of the sound phenomena found on records,” along with musical performance, timbre, echo, and ambience (reverberation).[83] Most generally, I agree with Wallace Berry,[84] who conceptualized texture as a comprehensive analytical category and pointed to the significance of texture for distinguishing between different kinds of music.[85]

The reason I consider texture to be a particularly fruitful object of study in relation to punk[86] is that the textural makeup of punk is intimately connected to the ways in which it is, or is ethically expected to be, produced and perceived. Similar to the metaphors discussed above that are used to describe punk’s musical aesthetics, texture is tied to embodied experience, specifically referring to “the quality of something that can be decided by touch.”[87] Although we cannot have such a tactile interaction with music – an epistemological entry point for methodological reflection may be found in the concept of audiotactile musicology formulated by Vincenzo Caporaletti[88] – we still translate the (touch) impressions from our experiential knowledge to categorize and make sense of the sounds we hear, for example, as “hard,” “rough,” “edgy,” “thick,” “dense,” or similar:

Texture always denotes some overall quality, the feel of surfaces, the weave of fabrics, the look of things. Words from visual and tactile sense modalities are often appropriated for descriptions of sounds and their combination: sharp, rough, dull, smooth, biting, bright, [...].[89]

Punk is strongly characterized by its peculiar texture, which can be defined in terms of its horizontal density and vertical homogeneity. Punk songs tend to have a high density of successive sound events that create a continuous layer over time – many fairly evenly paced, equally emphasized, and rapidly attacked down- and upstrokes,[90] or just downstrokes, on guitar and bass, occurring within short periods of time, merge with many rapidly alternating kick and snare drum strokes, as well as heavily hit, “sloshy”[91] open hi-hats with a long sustain. This particular density creates a constant, or “unbroken,”[92] flow that pervades the formal architecture, as there are usually no wide textural gaps or sudden dynamic changes throughout the songs.

The horizontal density goes along with a relatively homogeneous and tight vertical texture. In punk songs, there are usually not many independent sound streams criss-crossing the texture, but rather only a few that are unified, for example, by articulation, proximity, or direction of movement. The stringed instruments often form a common layer, but the vocals are also often multiplied into a layer of so-called “gang” vocals[93] or, especially in melodic hardcore or skate punk, of multi-part harmonies. Individual musicians’ contributions are usually not audible in all their detail, as the overall sound tends to be blurred and fused rather than split and defined.[94] An accompanying trope to this particular texture is that of the straightforwardness – “punks rejected slick production values”[95] – of the recording and mixing processes, which is linked to punk’s plug-and-play mentality or get-up-and-go immediacy. In this vein, Alan Moore has pointed to technological simplicity as a core element of punk:

Within the popular song of the last six decades, innovation has tended to come from two alternating tendencies. The first is greater simplification (‘folk’ was musically simple, ‘hit parade pop’ is lyrically simple, ‘punk’ was technologically simple).[96]

The specific texture makes the music seem like a collective group effort, with a corresponding collective power, rather than an individual act of self-expression or an “ostentatious display of ‘talent.’”[97] It thus represents the “collectivist enterprise” that David Easley and Steve Waksman ascribe to hardcore punk in particular:

In his study of punk and metal, Steve Waksman describes the performance of hardcore as a ‘collectivist cast’ in which all of the instruments – including vocalists – produced an effect ‘in which the various musical components were far less differentiated, and the players less individuated, than in other forms of rock’ (2009, 265). Although Waksman’s comment arises in a discussion of tempo, his observation is equally applicable to the role that riffs play […]. [R]iffs play a central role in the ‘collectivist’ enterprise found in hardcore.[98]

The fact that there are limits to what can be done with texture in punk is again evident when a band is denied to (still) being considered a punk band. This can happen, for example, when the horizontal density is too often interrupted by long notes and pauses or omissions of individual instruments, thus disrupting the constant flow of energy, or when the sound becomes wet and distant (so no longer punchy and urgent), due to features such as too much reverb. At the same time, the vertical texture can become too clear, widely-spaced, or thick due to too much top end, too much compression, and/or the addition of multiple accessory instruments and tracks.

There is a delicate balancing act between individualism and collectivity, as the individual musicians’ sound layers may become overly defined and disconnected from those of the others. For example, if one voice stands out too much from the texture, either in the mix or structurally, this can be to the detriment of the other voices, which are reduced to accompanying layers without any original contribution. As a result of these compositional, recording, or production choices, the musicians may have to live with the accusation that their music has become overproduced, too polished, or single-person-centred and thus too commercially driven to be punk.

Structure

Even though punk’s dense and tight texture is usually not supposed to make every little nuance audible, it still must leave enough space for structural clarity to redeem the above-outlined claim of immediacy – after all, punk is neither death industrial nor drone doom. From a cognitive point of view, punk tends to be a quick-to-grasp and strongly goal-oriented music. As a whole, punk songs are rarely longer than pop music’s standard three-and-a-half minutes (most often shorter) and typically formally adhere to the conventional verse-chorus scheme. Structurally, they are built upon short hooks or chordal riff patterns from the guitar, which, in their basic structure, often comprise just two bars, and are topped by four-bar vocal phrases. These elemental building blocks are collectively carried and strengthened by the bass guitar, which duplicates – or at least is strongly oriented towards – the guitar chords’ fundamental tones and a straightforward drum rhythm emphasizing heavy accents and a backbeat.

Moreover, punk is, against popular opinion, not dissonant music per se, but mostly, as David Pearson has pointed out,

harmonically and melodically consonant. Vocalists tended to deliberately eschew singing perfectly on pitch, though they did generally follow a melodic contour that matched the guitar chords and, as punk turned to hardcore, incorporated greater degrees of timbral distortion through yelling the lyrics. [...] Melodically, most punk riffs up until the 1990s stayed within the bounds of diatonic modality.[99]

The notion of dissonance does also not fully apply to the spectral characteristics of punk’s distorted guitar sounds. Even though the vertical texture of punk songs is overall somewhat indistinct, it is structurally not completely all over the place but rather still constructed in an orderly way. This is the result of the linear and full “chordy” sound of the fifth chord/powerchord, which, often complemented by the octave, includes many consonant overtones with simple ratios.[100] However, fortified with combination tones,[101] the heavily distorted powerchord remains one of the main drivers of punk’s foundational principles: energy and intensity.

Tensity

Eventually, the defining factor that bundles the textural and structural features of punk and makes them effective within the proposed framework, along with the metaphorical enclosures, ethical criteria, and core values of the state of mind, is the temporal tensity that these features create, which “works itself out aesthetically in the musical process”[102] and influences our aesthetic experience.[103] As noted above, the idea of texture inherently involves the processes of intensification and resolution, and also for Berry, texture is an essential element that functions “in processes by which intensities develop and decline, and by which analogous feeling is induced.”[104]

To interpret these processes in the specific context of punk, I adhere to the notion of an “imagined participation” with musical gestures, as proposed by Arnie Cox[105] and taken up by David Easley in relation to punk. Easley has pointed to intensity, energy, and aggression as the core tropes of hardcore punk and argues, with a focus on guitar riffs, for an “embodied understanding of these actions.”[106] He quotes Cox in saying: “Musical gestures are musical acts, and our perception and understanding of gestures involves understanding the physicality involved in their production.”[107] I propose that we foster such an understanding in a broader sense, with a view to punk’s defining texture and structure.

The highly taut horizontal texture of punk songs is a direct result of the physical effort involved in playing the music. This is important, first, for the audience’s embodied imagination of how the music is made, which distinguishes punk from similar textures found in electronically produced dance music, such as techno. The gestures embedded in this somatic “stomach-and-leg” oriented texture[108] convey punk’s abrasive “powerful affect,”[109] which can be considered the main method that punk musicians use for their specific kind of cultural negotiation. Since punk’s state of mind is constituted through the critical discursivization of dominant conceptions, it has to process them in some relational way in the sense of inverting its aesthetics as a negative that still remains identifiable. What punk musicians have effectively done, then, is to translate the structural immediacy of one of dominant society’s main cultural evaluation surfaces – pop music – into their own musical language,[110] making it energetic and aggressive by punk’s own, but already rather constricted and predetermined, means. As Pearson put it:

Early punk was not a qualitative increase in tempo beyond previous rock, but perhaps the feeling of speed was intensified due to the relentless energy of riffs, heavy hits on the drums, and the frantic style of singing.[111]

This translation is well illustrated by the main rhythmic backbone of both pop and rock music, which is, or was until a few years ago, the backbeat pattern in 4/4 time, with its higher frequency accents on 2 and 4. Punk drummers were early adopters of this pattern, creating a faster and louder version of it in different shades and with increasing intensity over time. Eric Sandin, the drummer of the pioneering punk band NOFX, has explained and demonstrated this development in a video snippet, where he shows how he invented the band’s trademark drum beat by learning the basic two-bar drum beat of Iron Butterflies’ “In-A-Gadda-Da-Vida” in a fast tempo (“I just got that kind of fluid and sped it up”).[112]

Considering the importance of these adapted drum beats as instant markers of a whole genre, it must be considered a blind spot that their peculiarities and evolution have rarely been scholarly analyzed.[113] I propose that we look at them not only as a steady rhythmic fundament or accompanying layer, but that we also analyse their role as (rhythmic) hooks, structural markers, movement generators, and tensity-regulating instances. From the very basic pattern with the kick drum on the downbeats 1 and 3, to the galloping doubled “skate punk” kick drum on 3 and 3+, and the more displaced 2+ and 3+ “d-beat,” as well as the downbeat “polka” beat (technically not a backbeat) – all of these beats, albeit encapsulated within a fairly rigid framework and “anti-syncopation tendency,”[114] provide different affordances for groove synchronisation, for example, through their constant down-and-up movement pattern gesturality,[115] as well as particular emphases and spaces to which the other voices can adjust, for instance, in the handling of small-scale tension-resolution patterns.[116]

This is a crucial point insofar as, within the already high level of intensity and forward drive, the dense and evenly composed horizontal texture, and the repeated short and structurally narrow units of punk songs, there are limited possibilities to influence the listener’s aesthetic experience through, as I have put it elsewhere with reference to Berry, the “dialectical balance between intensifying and resolving tendencies,”[117] or the arousal of embodied meanings through the creation of (un)certain expectations.[118] Since punk songs usually do not offer cross-phrase tension arcs, period-structure-like[119] build-ups, or massive dynamic changes (as best exemplified by 1990s grunge, with its verse-undistorted-quiet/chorus-distorted-loud dynamics),[120] I think it is worth looking at how intensity is punctually increased and decreased, for example, through processes of anticipation, contraction, acceleration, and deceleration.[121]

The vocal lines of punk song verses, for example, tend to be rather closural at the phrase level. The singers often mark the boundary of a phrase by returning to the root or initial note followed by a pause. To introduce some dynamics, the melodic cells within often start on the 1+ of a 4/4 beat, creating a slight sense of tension that is released when the motive is resolved with a stressed syllable on a strong downbeat.[122] Similarily, the cells sometimes also begin on the anacrustic 4+, allowing the singer to carry more energy into the subsequent 1.[123] In addition, the vocal lines tend to be rather straight and stay within a fairly small ambitus, as they interlock with the overall textural and structural linearity. As a result, tension is not created by large melodic leaps calling for stepwise resolution – such disjunctive melodic movement would also make singing/shouting along more difficult – but rather by short melodic bursts up or down[124] and/or by rhythmic and melodic nuances that create friction and ambiguity by, for instance, scooping – like when sliding down to a motive-ending note preceded by a chain of densely packed syllables –,[125] or rapid periodic “vibrato”[126] or constant “out-of-tune” pitch deviations.[127]

In punk, there are direct links between the high physical demands of playing the music, its structural-tensional culmination points, and its intonation and pitch-structure characteristics. For example, a fairly obvious reason why punk drummers regularly emphasize structural cornerstones, such as the heavy downbeat with strong cymbal shots, is to provide notable landmarks or target points within their forward-driven motion. However, the crash and ride cymbal emphases can also help the drummers take a short break while keeping the tempo up, by unobtrusively skipping a few notes on the hi-hat just before hitting the other cymbals. These short omissions may subtly increase the tension towards the anticipated downbeat, thus giving it more weight. Likewise, using the “shank-tip” technique on the hi-hat may not only help relieve the joints, but also create an additional heavy-light pattern within the long chains of eighth notes.[128]

As the latter examples show, punk’s musical makeup can also be considered the result of being economical in order to ensure longevity. Another example in this context concerns punk’s riff schemes. On the one hand (i.e., literally the right hand of a right-handed guitarist), punk guitarists often have to execute these riffs with rapid, successive downstrokes. In a video of their first public rehearsal with their new drummer Josh Freese, the members of the Foo Fighters ironically show how exhausting this can be after performing “Everlong” (“eighth-note city, man!”, “downstroke practice!”). The band’s lead guitarist, Chris Shiflett, formerly of skate punk band No Use For A Name, then explains: “That’s why all the 90s’ punk songs go like this (plays three times a fast sequence of two palm-muted eighth-note powerchords followed by an unmuted quarter-note powerchord). It gives you a little break (laughing).”[129]

The technique described by Shiflett, which can be heard in many variations in the punk cosmos,[130] not only gives the guitarist a short break, but also adds small cracks in the horizontal texture and thus brief fluctuations in tension and rhythmic accents. A similar but opposite effect of brief textural contractions and accelerations is achieved by interspersing sixteenth-note alternate pickings into the guitar riffs,[131] sometimes corresponding to the doubled kick drum or single stroke rolls on the snare drum.

On the other hand (i.e., literally the left hand of a right-hander), the pronounced physicality of punk certainly also sets limits to what can be played, in addition to the need to provide an effective means of engaging the audience through clear, familiar, and easy-to-process musical structures.[132] It is the speed of the music combined with its timbre- (rather than harmony-) oriented chordal riffing[133] that limits the range of motion on the guitar and thus the choice of scale degrees. Music theory YouTuber Cory Arnold makes this especially clear when he notes that the hand movements of punk guitarists must be very economical, because the movement of the single locked-down powerchord posture comes from the wrist rather than the fingers, which makes it difficult to attack distant positions on the fretboard. Metal (lead) guitarists, on the contrary, tend to play single-note lines and thus have more motor flexibility in using their different fingers to play “massive, sweeping riffs running all up and down the neck, using whatever notes they want.” Consequently, seconds and fourths, which are close together, are natural choices for punk songs.[134]

After all, since the live performance of the music must not differ significantly from the recorded sounds, the obligatory jumping, running, floundering, head-nodding, floor-crawling, and similar tension-raising activities that take place on stage are certainly not conducive to shredding wide-ranging, difficult-to-grasp harmony progressions or stacking polymetrically-nested tuplets.

Conclusion

In this article, I have suggested different anchor points that hold together what punk tends to be. I have also elaborated on the value of a music-oriented analysis of such a framework. My main point here is that there is a reason, or many interconnected reasons, for why punk sounds the way it does, and to complete my theory building, a music-oriented horizon of punk scholarship might read as follows:

Studying punk helps us better understand the discursive and circular-processual relationship between a community’s ingrained attitudes, its aesthetic forms of expression, and a society’s dominant conceptions, the latter mirrored in the mainstream frame of cultural debate, by analyzing how the relationship is (re-)negotiated, stabilized, and renewed with regards to ethical notions of physicality, immediacy, and collectivity and the associated aesthetic notions of texture, structure, and tensity.

What I have added in this iteration of my theory are the aesthetic notions described above, as well as the idea of mainstream popular music as a cultural mirror to “a society’s dominant conceptions.”[135] For punk protagonists in particular, the idea of or the attribute of “mainstream” is not only strongly evaluative in a negative sense (as the punk term was initially as well), but also integral for punk as an opposing concept – also, and perhaps especially, in aesthetic terms, because “[w]hat is constituted (and rejected) as music is an outcome of genre negotiations and conventions.”[136] In the case of punk, these negotiations are strongly bound up with (the rejection of) mainstream notions – but with brittle boundaries, as I have indicated a few times in the present work. As opposed to punk, mainstream popular music does not refer to a genre category, nor does it have a stable or enduring nature, but rather a processual one that is tied to the zeitgeist, prevailing discourses, and “fashions and trends of the day.”[137] Punk has established particular ethical and aesthetic concepts to challenge mainstream notions, including the idea that it should not become pre-processed, polished, cut-and-dried, overproduced, or mass-appealing music made solely out of commercial interest and without historical foundations. Due to its strong relationship to the mainstream frame, though, it is possible that punk may sometimes slip into these traps.

However, despite the importance of this relationship, it should not be forgotten that the pleasures of listening to or making punk music can certainly transcend its “political orientation” in the broadest sense. As Michelle Phillipov put it:

By centring studies on the political orientation of punk, music is subordinated to a function of these politics, rather than something which generates pleasures and meanings in its own right. These are not merely questions of identity and social location and resistance; these are things cultural studies already has a sophisticated vocabulary for talking about. It is the ‘other stuff’ of music, the specific pleasures of the sounds and textures of the music itself, that we have much more difficulty finding the language to express.[138]

It is my view that a music-oriented scholarship of punk may help us find this language.

Notes

In this article, I use the terms “punk” and “punk rock” synonymously, as the musical connotation is usually the same. I therefore agree with Dirk Budde, who in his book Take Three Chords also refrains from making a distinction between punk rock and punk: “To paraphrase David Laing, ‘punk’ also stands for the musical expression of the phenomenon that is the focus of this work. There is no need to discuss the fact that ‘punk’ can also be understood as an extra-musical phenomenon” (Budde 1997, 192; author’s translation). | |

Shukaitis 2012, 129. | |

Rapport 2014, 44. | |

I first presented my thoughts in this article in my keynote at the conference Horizons of Punk: Punk-Rock Scholarship and its Methodologies in Paris, France, 9 June 2023. | |

See Marshall 2011, 159; Steinbrecher 2021b, 408. | |

Laing 2015, 8. | |

Die Ärzte 2012; author’s translation. | |

Joseph Boys 2023; author’s translation. | |

This introductory step might reasonably be seen as problematic or perhaps even lazy. However, my intention was to initially approach the discourse with a relatively open perspective and with as small scholarly blinders as possible. Given my personal and academic background in the field (see also note 14), I believe I can evaluate the information gathered in a reflective manner and will frequently reference the extensive body of literature throughout this article. | |

ChatGPT, response to “what is punk?”, Open AI, 25 May 2023. https://chat.openai.com/chat. | |

ChatGPT, response to “what is punk?”, Open AI, 23 September 2024. https://chat.openai.com/chat. | |

Way 2021, 107. | |

Ibid., 112. | |

I am, of course, fully aware that the list of attributes that I consider to be “common traits” here and in the rest of the article is neither complete nor comprehensively substantiated by, for example, an extensive discourse or keyword-in-context analysis. Accordingly, my reflections are based on my own experiences as a punk researcher, fan, and musician, as well as on the recurrent appearance of these attributes in dictionaries, encyclopaedias, documentaries, interviews, journalistic books, biographies, and academic works. One particular example is the 2022 documentary Punk In Drublic, in which many seminal punk musicians share similar perspectives when asked about what punk is/means for them (0:02:30–0:04:55). The same applies to various comments in the 1981 punk documentary The Decline of Western Civilization. | |

See, e.g., Hebdige 1991, Ableitinger 2004, and Laing 2015. | |

“Punk established the blueprint for many forms of contemporary DIY cultural production, notably in relation to music production, fanzine culture and fashion design” (Bennett/Guerra 2023, 4). | |

McKay 2024. | |

As indicated in the left-hand column of my framework, it might be worth considering who the main actors of these negotiations are as to matters of identity construction. This is because, traditionally, punk has been coded as male, white, and (by and for the) young: “[Y]ou must be young, White, and an underachiever to perform punk music in an exemplary fashion (Laing 1985)” (Lena/Peterson 2008, 706). Brett Gurewitz of Bad Religion and Epitaph records notes that he has still adhered his initial ideals when running his business, even though he is “not a teenager anymore and punk is music for teenagers” (as cited in Diehl 2007, 158). Way, with reference to Hebdige, remarks that “Commonly, punk was theorised as both a male-dominated subculture and one which was youth centred” (2021, 108). | |

Graffin 2022, 360. | |

Way 2021, 119. | |

Holt 2007, 2. | |

Lena/Peterson 2008, 698. | |

Fabbri 1982, 52–55. | |

See also Toynbee 2000, 104–107; Fabbri 1982, 59. | |

Nowak/Whelan 2022, 10. | |

Ibid., 12. | |

Lena/Peterson 2008, 708. | |

Hoper 2002 as cited in Diehl 2007, 137. | |

In a 2025 interview with the newspaper Süddeutsche Zeitung, the singer of the German punk band Team Scheisse, Timo Warkus, reiterates this notion when asked about his band’s current popularity: “There is no concept. The fact that we resonate so strongly with people right now is simply down to the fucking zeitgeist. The zeitgeist automatically ensures that it has to be constantly renegotiated what punk actually is and what it isn’t.” (Hentschel 2025; author’s translation). | |

Nowak/Whelan 2022, 10. | |

Lena/Peterson 2008, 713. | |

Joseph Boys 2023; author’s translation. | |

Shea et al. 2024. | |

Pearson 2019, paragraph 1. See also Easley: “Despite being the focus of studies in fields such as ethnomusicology, cultural studies, philosophy, and history, punk rock – and American hardcore punk rock in particular – has yet to fall under the analytical gaze of music theorists” (2011, xviii). | |

Budde 1997. | |

Easley 2011. | |

Steinbrecher 2016. | |

Rapport 2020. | |

Lee 2022, 10. | |

Pearson 2019. | |

Easley 2015. | |

Rapport 2014. | |

Bennett 2015. | |

Cateforis 1993. Some song analyses, e.g., from “Blitzkrieg Pop” (Ramones), “The Passenger” (Iggy Pop), “London Calling” (The Clash), “Schrei nach Liebe” (Die Ärzte), “Self Esteem” (The Offspring), and “All The Small Things” (Blink 182) can also be found in the Songlexikon encyclopedia. | |

Laing 2015, 46–52. | |

Lena/Petersen 2008, 713. | |

Pearson 2019, paragraph 5. | |

Punk Attitude 2005, 0:00:12–0:00:25. | |

A “skank” beat refers to a rhythmic pattern on the drums, particularly used in hardcore punk, in which kick and snare strokes alternate rapidly, at speeds of 150 BPM upwards. The offbeat phrasing of the snare drum, in a skank upbeat, resembles the characteristic “skank” guitar strokes of ska or reggae (Lee 2022, 141–142). | |

One + One 1968, 0:01:40. | |

Again, these descriptions can be found in numerous (academic and non-academic) resources, which I will not list individually here. Perhaps it is worth mentioning that the aspect of aggression has also found its way into the title of an edited volume (Abbey/Helb 2014). | |

See also Pfleiderer 2006, 96. | |

In the context of music, see, e.g., Snyder 2000; Bruhn 2005. | |

See also Thies 1982. | |

See also Steinbrecher 2016, 66–85. | |

See Herbst/Mynett 2022. | |

For the concept of “musicking,” see Small 1998. | |

See Diaz-Bone 2002; Steinbrecher 2016, 154–183. | |

Many punk scholars approaching the genre from something other than a musical perspective will probably disagree with me at this point, given the plethora of philosophical, media-theoretical, political, or other readings of certain kinds of punk. In my opinion, however, these top-heavy streams of punk are not necessarily the ones that have contributed most to the genre’s ongoing relevance or popularity. | |

Steinbrecher 2024; Steinbrecher 2025. | |

Steinbrecher 2025, 18. | |

Toews 2023. | |

Lee 2022, 33–50. | |

Laing 2015, 19. | |

Rapport 2014, 48. | |

Pearson 2019, paragraph 13. | |

Hall 1969. For an application of Hall’s theory of proxemic zones to the analysis of popular music, see Moore/Schmidt/Dockwray 2011. | |

See also Abrams 2009, 305–314; Steinbrecher/Pichler 2021, 21–24. | |

Pistol 2022. | |

Ibid., 0:22:55-0:23:35; see also Steinbrecher 2024, 236. | |

“The drumming” 2014, 0:00:50–0:02:00. | |

Christofer Jost uses the term “praxis formation” in connection with the analysis of mainstream popular music (2019, 0:20:40–0:21:05). But I think it is also productive to look at punk from the perspective of a complex of doings and sayings that are regularly interlinked and operationally related to each other (Hillebrandt 2014, 59; see also Klose 2019). | |

See also Steinbrecher 2021b, 408; Marshall 2011. | |

The notion of a common ground may also be discussed with the question of repetition and difference: “[G]enre needs to be seen as a process in which the tension between repetition and difference fundamental to all symbolic forms is regulated. […] Certainly hardcore musicians keep on going back to the ‘same’ music, but in doing so they inflect their sound as they strive, but fail, to achieve an ideal, original aesthetic effect. […] What seems to be at stake is an exploration of the limits of repetition within a spectrum of musical parameters” (Toynbee 2000, 106). | |

Fabbri 1982, 54–59. | |

I do not deny that all sorts of musicians, from Wolfgang A. Mozart onwards, have been considered punk (as have golfers and business investors), and sometimes even the music of such unrelated figures has been classified as such, even though it may not contour any of the musical traits I am describing here. However, similar to vice-versa cases, i.e., when musicians such as former rapper Machine Gun Kelly suddenly adopt very strong musical markers of punk but without fulfilling some (or enough) other criteria, the interlockings will not snatch and remain unsustainable (as described by a Reddit user: “MGK is a tourist in the [pop punk] genre” (u/mattburkephoto 2023)). For a critique on postmodernist approaches towards punk, and the notion of musical arbitrarity that these often indicate, see Pearson 2023. | |

The framework differentiates between three basic levels of analysis (surface, individual voices, and interrelationships) and suggests four focal points of a process-oriented analysis (grouping effects, progression tendencies, intensity curves, and movement patterns) (Steinbrecher 2016, 135–146). | |

Smith 2023, paragraph 1.8. | |

Griffiths 2003. | |

Pfleiderer 2003, 20–22. | |

Popular music scholars who have argued or worked in a similar vein are, e.g., Moore and Martin 2019, 281; Butler 2006; Bennett 2015; Peres 2016. | |

Zak 2001, 85. | |

Ibid., 49. For more about these categories see 48–96. | |

Berry 1987, 184–300. | |

Ibid., 293. However, I disagree with him regarding textural simplicity as being the distinguishing feature between “[challenging and interesting] ‘art’ music as opposed to […] ‘popular’ […] music” (293), not least because he does not (or technically cannot) consider the “structural functions of coloration (of timbral differences, of orchestration, etc.)” (20–21). | |

In his discussion about the process of excursion from, and return to, a sound schema in hardcore punk, Toynbee emphazises the importance of original compositions, or “standard tunes,” because “[t]hey are a key component of generic method, a tool for producing small variations along a bed of iterated texture“ (Toynbee 2000, 107). | |

Cambridge Dictionary, s.v. “texture,” https://dictionary.cambridge.org/dictionary/english/texture (2 Feb 2025). | |

Caporaletti 2018. “What name we can give to that specific poietic and receptive psycho-physical modality we have so far dwelt upon [e.g., regarding continuous pulse and groove], and especially its cognitive medium quality [...] characterizing with such depth the languages of rock, jazz, world music, and pop music itself? I call it audiotactile principle (ATP), in the symbolic sense of both aural and tactile perception – as distinct from the “visual” archetype – as factors identifying two specific and related modalities in which the subject’s musical cognitive experience unfolds [...]” (7). | |

Erickson 1975, 139. | |

In reference to the seminal German punk band Die Toten Hosen, the term “Hosen-Hobel” (literally “Hosen slicer”) has been coined, which is a term of endearment for the band’s fast and distinctive style of guitar playing (exemplified, e.g., in the songs “Liebeslied” and “Warten auf Dich”). | |

Toews 2023. | |

Laing 2015, 52. | |

Samantha Bennett has pointed to this effect with regards to some Sex Pistols’ songs (2015, 13). Other bands using “gang” vocals extensively include, e.g., Die Toten Hosen, Rancid, Pennywise (“Bro Hymn”), Dropkick Murphys, Anti-Flag, and PUP. To illustrate my analytical thoughts in the following pages, I will reference a number of different examples rather than analyzing a single song extensively from multiple perspectives. Focusing on one song would put undue emphasis on it, potentially flagging it as a prototypical punk song – an outcome I believe would not contribute productively to the discourse I aim to initiate here. | |

For the relationship of “Spaltklang” (“split sound”) and “Schmelzklang” (“melting sound”) in rock music, see Herbst 2016, 75–78. | |

Prinz 2014, 586. | |

Moore 2012, 143. As Bennett showed, the narrative of technological simplicity can be challenged, at least when it comes to one of the blueprint punk albums, the Sex Pistols’ Never Mind The Bollocks: According to Bennett, “the technological and processual means by which the album was recorded lend it a sonic character that does not align with punk aesthetics at all; recorded at Wessex studios, London, between late 1976 and mid-1977, the record is a product of large-scale, 1970s classic rock-album production” (2015, 466). | |

“Many punk performers are actually skilled musicians, but the prevailing ethos says: we just picked up some instruments and started playing in our basement” (Prinz 2014, 586). | |

Easley 2015, paragraph 2.1. Easley adds that “although other features such as timbre and texture play equally important roles in this music, my focus is on the more traditional, ‘primary’ parameters of pitch, rhythm, and form” (2015, paragraph 10). | |

Pearson 2019, paragraph 37. | |

Herbst 2016, 188. | |

Lilja 2015. | |

Stambaugh 1964, 278. | |

Steinbrecher 2021a; see also Lehne/Koelsch 2015, 286. Joan Stambaugh’s (1964) philosophical reflections on aesthetic time in music suggest the use of the term “tensity” as a superior concept to notions of tension and resolution. She writes: “Musical tensity lies in the relation of the tones, in the peculiar continuity of transition between them, a short of tensity between tensions. [...] Tensity must necessarily find a resolution, but this resolution does not cancel it out. This tensive relation generates the temporal factor in progression, the whole moving in the moment which drives towards explicating, detensifying this whole within it. This is temporal tensity” (1964, 277–278). | |

Berry 1987, 4. | |

Cox 2006, 46. | |

Easley 2015, paragraph 1.2. | |

Cox 2006, 45 as cited in Easley 2015, paragraph 7.1. | |

Regarding punk’s somatic perception, I see some parallels with what the musicologist Peter Wicke and the philosopher Martin Seel ascribe to techno, as “literally tactile music […] redirected to the body as a reference, to physical movement, physical experience and the symbolic mediation of this” (Wicke 1998, 8; author’s translation), or a sound that is “to be understood as the attempt to make music that can be listened to somatically […] as a direct transfer of the energy of the work to the physical condition of its listener” (Seel 2003, 248; author’s translation; see also Steinbrecher 2016, 82–83). | |

Rapport 2014; see also Phillipov 2006. | |

This is perhaps loosely comparable to the mechanisms of “hyper pop” that emerged in recent years. The hyper pop artists’ methods are certainly different, as they use, among other tools, alienation and rhythmic displacement as a means of negotiating pop music. | |

Pearson 2019, 3. Steve Waksman, in his monograph on heavy metal and punk, addresses the interrelationship of tempo, physicality, and demarcation, noting that: “While earlier punk bands such as the Ramones and the Sex Pistols used speed to announce something of a break with earlier rock styles, hardcore placed even more emphasis on acceleration. The quickened pace of hardcore was the musical analogue of, even the precondition for, the physical intensity of slam-dancing: it was attached to the hardcore strategy to reduce rock to certain core elements, and it was a means of demonstrating the hardcore commitment to an extreme sound and style of performance” (Waksman 2009, 258–259). | |

Sandin published the video on Facebook. It is not longer online, but I made a screen video which can be watched here: https://drive.google.com/file/d/1LFP9RsLCRT4J8P53jzdt-n-9GAjeu53z/view?usp=sharing. | |

Sangheon Lee gives a couple of analytical examples of different punk beats throughout his dissertation (Lee 2022). | |

Laing 2015, 52. | |

In his dissertation on EDM, Hans Zeiner-Henriksen argues that the alternation of low and high frequencies, such as between bass drum and hi-hat sounds, supports specific body movements, which he calls “vertical movement patterns” (Zeiner-Henriksen 2010). | |

“Tension-resolution patterns refer to the opposite poles of tension – a state of instability or dissonance associated with feelings of hopeful (or fearful) expectation – and its counterpart, resolution, relaxation, release, or repose” (Lehne/Koelsch 2015, 286). | |

Steinbrecher 2021a, 121. | |

Meyer 1956, 35; for further readings on the idea of a process-oriented analysis, see, e.g., Narmour 1992; Hasty 1997; Fuß 2005. | |

Moore 2012, 76–89. | |

This “juxtaposition of radically different textures” in early 1990s alternative rock is also mentioned by Zak (2001, 93). The fact that breaking with the horizontal density or vertical tightness constitutes a certain departure from punk was also apparent some years earlier, as in the cases of the post-punk and post-hardcore currents that started to emerge in the early 1980s with their angular rhythms, high-frequency actions, or stop-and-go aesthetics. | |

See also Steinbrecher 2021a, 137–138. | |

E.g., “New Rose” (The Damned), “Still Waiting” (Sum 41). | |

E.g., “Ever Fallen In Love (With Someone You Shouldn’t’ve)” (The Buzzcocks), “Banned in D.C.” (Bad Brains). | |

E.g., “Blitzkrieg Bop” (Ramones), “Anarchy in the UK” (Sex Pistols). | |

E.g., “Turnover” (Fugazi; see Steinbrecher 2016, 184–206), “I Wanna Be Sedated” (Ramones), “Rise Above” (Black Flag), “Allegleich” (Joseph Boys), “Sweet Brown Water” (Bad Cop, Bad Cop), “Schunder Song” (Die Ärzte). I have identified a similar technique of creating tension and resolution also in contemporary rap (Steinbrecher 2021a, 133–137). | |

E.g., “Teenage Kicks” (The Undertones), “No Feelings” (Sex Pistols), “California Uber Alles” (Dead Kennedys). | |

To my knowledge, however, the notion that punk vocalists sometimes go off key has not yet been systematically investigated. Due to the peculiarities of their vocal delivery (e.g., “talk-singing,” screaming), it may also be difficult to make concrete statements about this. As Nichols et al. put it: “Singing in tune, or singing accuracy, is a construct dependent on genre, key selection, singers’ ranges, and listener expectations” (2022, 1414). | |

Not being a good drummer myself, I became aware of these techniques or “tricks” by watching tutorials on playing punk beats, where they are repeatedly mentioned. See, for example, “5 Ways,” 0:10:17–0:15:47; “Eugene,” 0:06:20–0:07:43; “Skank,” 0:05:25–0:09:57. I suppose it would be interesting to analyze how these or similar energy-saving techniques have actually been used in songs or live performances. Essentially, to consider these kinds of non-academic knowledge-transfer sources, including online discussions about playing or production techniques, is crucial for understanding how punk, according to Nowak and Whelan (2022), is being worked on as a genre. | |

“Preparing” 2022, 0:47:10–0:50:32. | |

E.g., “Soul Mate” (No Use For A Name), “Basket Case” (Green Day), “Territorial Pissings” (Nirvana), “Welcome to the Black Parade” (My Chemical Romance), “All in my Head” (The Linda Lindas). In an online tutorial about punk-rock style palm muting, the tutor points to the importance of this technique “to get a rhythm” and not sound monotonous (“Learn all,” 0:03:46–0:04:49). | |

E.g., “72 Hookers” (NOFX), “Hate, Myth, Muscle, Etiquette” (Propagandhi). | |

Axel Kurth, the singer of the popular German punk band Wizo, even sees significant parallels between punk and children’s songs (Kurth 2022). | |

Pearson 2019, paragraph 5. | |

“How To” 2022, 0:03:21–0:07:04. | |

Steinbrecher 2021b, 410. | |

Nowak/Whelan 2022, 10. | |

Steinbrecher 2021b, 409. | |

Phillipov 2006, 390; see also Pearson 2019, paragraph 41. |

References

Ableitinger, Martin. 2004. Hardcore Punk und die Chancen der Gegenkultur. Analyse eines gescheiterten Versuchs. Hamburg: Kovač.

Abrams, Dominic. 2009. “Social Identity on a National Scale. Optimal Distinctiveness and Young People’s Self-Expression Through Musical Preference.” Group Processes & Intergroup Relations 12/3: 303–317. https://doi.org/10.1177/1368430209102841

Die Ärzte. 2012. “Ist das noch Punkrock?” auch. Hot Action Records.

Bennett, Andy / Paula Guerra. 2023. “DIY, Alternative Cultures and Society.” DIY, Alternative Cultures & Society 1/1: 3–6. https://doi.org/10.1177/27538702221134896

Bennett, Samantha. 2015. “Never Mind the Bollocks: A Tech-Processual Analysis.” Popular Music and Society 38/4: 466–486. https://doi.org/10.1080/03007766.2015.1034508

Berry, Wallace. 1987. Structural Functions in Music. Englewood Cliffs, N.J.: Prentice-Hall.

Bruhn, Herbert. 2005. “Wissen und Gedächtnis.” In Allgemeine Musikpsychologie, edited by Thomas Stoffer and Rolf Oerter. Göttingen: Hogrefe, 537–590.

Budde, Dirk. 1997. Take Three Chords. Punkrock und die Entwicklung zum American Hardcore. Karben: Coda.

Butler, Mark. 2006. Unlocking the Groove: Rhythm, Meter, and Musical Design in Electronic Dance Music. Indiana: Indiana University Press.

Caporaletti, Vincenzo. 2018. “An Audiotactile Musicology.” RJMA – Journal of Jazz and Audiotactile Musics Studies, English Notebook, 1: 1–17. https://www.nakala.fr/nakala/data/11280/a2a708e8 (9 May 2025)

Cateforis, Theo. 1993. “‘Total Trash’: Analysis and Post Punk Music.” Journal of Popular Music Studies 5: 39–57.

Cox, Arnie. 2006. “Hearing, Feeling, Grasping Gestures.” In Music and Gesture, edited by Anthony Gritten and Elaine King. Hampshire: Ashgate, 45–60.

Diaz-Bone, Rainer. 2002. Kulturwelt, Diskurs und Lebensstil. Eine diskurstheoretische Erweiterung der bourdieuschen Distinktionstheorie. Opladen: Leske + Budrich.

Diehl, Matt. 2007. My So-Called Punk: Green Day, Fall Out Boy, The Distillers, Bad Religion – How Neo-Punk Stage-Dived Into the Mainstream. New York: St. Martin’s Publishing Group.

Easley, David. 2015. “Riff Schemes, Form, and the Genre of Early American Hardcore Punk (1978–83).” Music Theory Online 21/1. https://doi.org/10.30535/mto.21.1.3

Easly, David. 2011. “‘It’s not my imagination, I’ve got a gun on my back!’: Style and Sound in Early American Hardcore Punk, 1978–1983.” PhD thesis, Florida State University.

Emirbayer, Mustafa. 1997. “Manifesto for a relational sociology.” New School for Social Research 103/2: 281–317.

Erickson, Robert. 1975. Sound Structure. Berkeley and Los Angeles: University of California Press.

“Eugene Ryabchenko - How To Play Skank Beats? (Part 1/2 - The Basics).” YouTube, uploaded by Eugene Ryabchenko, 15 July 2017. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=91kPRTIJcRU (9 May 2025)

Fabbri, Franco. 1982. “A Theory of Musical Genres: Two Applications.” In Popular Music Perspectives, edited by David Horn and Philip Tagg. Göteborg, Exeter: IASPM, 52–81.

“5 Ways To Improve Your Punk Drumming.” YouTube, uploaded by Drumeo, 3 December 2021. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=EhHWPEXEWSs (9 May 2025)

Fuß, Hans-Ulrich. 2005. “Musik als Zeitverlauf. Prozeßorientierte Analyseverfahren in der amerikanischen Musiktheorie.” Zeitschrift der Gesellschaft für Musiktheorie 2/2–3: 21–34.

Graffin, Greg. 2022. Punk Paradox. New York: Hachette.

Griffiths, Dai. 2003. “From Lyric to Anti-Lyric: Analysing the Words in Popular Song.” In Analysing Popular Music, edited by Allan F. Moore. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 39–59.

Hall, Stuart. 1969. The Hidden Dimension. London: The Bodley Head.

Hasty, Christopher. 1997. Meter As Rhythm. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Hebdige, Dick. 1979. Subculture. The Meaning of Style. London and New York: Routledge.